Maritime transport (or ocean transport) and hydraulic effluvial transport, or more generally waterborne transport, is the transport of people (passengers) or goods (cargo) via waterways. For centuries, mankind has used waterways to transport merchandise and people. As such, maritime transport owes its evolution to international trade development and the ever-growing exchange of goods between countries. By definition, maritime transport is international (except when sailing along the coasts of the same country). Nowadays, maritime transport is the main means of transport used to ship raw materials (oil, coal, cereals, etc.) over long distances. Maritime transport refers to a means of transport where goods (or people) are transported via sea routes. In some cases, maritime transport can encompass pre- and post-shipping activities. The creation of maritime containers in the middle of the 1960s vastly encouraged the development of maritime transport. These standardized boxes pile one on top of the other and can transport all sorts of goods with a quite easy handling. Maritime containers have other advantages in that they limit the risk of damage, breakage and theft (the goods are not visible from the outside) and reduce transport costs.

It should be noted that the race to gigantism over the last few years (with ships able to transport more and more goods) has slowed somewhat. Ship-owners are having trouble filling their vessels and accessing the different trade ports worldwide. Maritime transport is an appealing means of transport, thanks to:

- Its transport capacity: several hundred tons of goods can be transported on a single ship;

- Its permanent activity: out at sea, nothing or practically nothing can stop vessel traffic.

However, maritime transport suffers from fairly slow movement (between 30 and 50 km/h for most vessels). It, therefore, entails much longer delivery lead times than road or air channels. There are two main maritime transport offers available: demand responsive transport (also known as tramping) and liner transportation. The first is when a request triggers the search for a ship to transport goods. The second is when the exporter selects a liner transportation offer with a set itinerary and frequent ports of call and shares the vessel with other exporters. Freight transport by sea has been widely used throughout recorded history. The advent of aviation has diminished the importance of sea travel for passengers, though it is still popular for short trips and pleasure cruises. Transport by water is cheaper than transport by air, despite fluctuating exchange rates and a fee placed on top of freighting charges for carrier companies known as the currency adjustment factor. Maritime transport accounts for roughly 80% of international trade, according to UNCTAD in 2020.

Maritime transport can be realized over any distance by boat, ship, sailboat or barge, oceans and lakes, canals or rivers. Shipping may be for commerce, recreation, or military purposes. While extensive inland shipping is less critical today, the major waterways of the world, including many canals, are still very important and are integral parts of worldwide economies. Particularly, especially any material can be moved by water; however, water transport becomes impractical when material delivery is time-critical such as various types of perishable produce. Still, water transport is highly cost-effective with regular schedulable cargoes, such as trans-oceanic shipping of consumer products – and especially for heavy loads or bulk cargo, such as coal, coke, ores, or grains. Arguably, the industrial revolution took place where cheap water transport by canal, navigations, or shipping by all types of watercraft on natural waterways supported cost-effective bulk transport.

Containerization revolutionized maritime transport starting in the 1970s. “General cargo” includes goods packaged in boxes, cases, pallets, and barrels. When a cargo is carried in more than one mode, it is intermodal or co-modal. A nation’s shipping fleet (merchant navy, merchant marine, merchant fleet) consists of the ships operated by civilian crews to transport passengers or cargo from one place to another. Merchant shipping also includes water transport over the river and canal systems connecting inland destinations, large and small. For example, during the early modern era, cities in the Hanseatic League began taming Northern Europe’s rivers and harbours. Similarly, the Saint Lawrence Seaway connects the port cities on the Great Lakes in Canada and the United States with the Atlantic Ocean shipping routes, while the various Illinois canals connect the Great Lakes and Canada with New Orleans. Ores, coal, and grains can travel along the American Midwest rivers to Pittsburgh or Birmingham, Alabama. Professional mariners are known as merchant seamen, merchant sailors, and merchant mariners, or simply seamen, sailors, or mariners. The terms “seaman” or “sailor” may also refer to a member of a country’s navy. According to the 2005 CIA World Factbook, the total number of merchant ships of at least 1,000 gross registered tons worldwide was 30,936. In 2010, it was 38,988, an increase of 26%. As of December 2018, a quarter of all merchant mariners were born in the Philippines. Statistics for individual countries are available in the list of merchant navy capacity by country. The environmental impact of shipping includes greenhouse gas emissions and acoustic and oil pollution. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) estimates that Carbon dioxide emissions from shipping were equal to 2.2% of the global human-made emissions in 2012 and expects them to rise 50 to 250 per cent by 2050 if no action is taken.

Ships

Ships and other watercraft are used for maritime transport. Types can be distinguished by propulsion, size or cargo type. Recreational or educational craft still use wind power, while some smaller craft uses internal combustion engines to drive one or more propellers, or in the case of jet boats, an inboard water jet. In shallow-draft areas, such as the Everglades, some craft, such as the hovercraft, are propelled by large pusher-prop fans.

Most modern merchant ships can be placed in one of a few categories, such as:

IMO and Maritime Transport Policy

Maritime transport is an essential component of any programme for sustainable development because the world relies on a safe, secure and efficient international shipping industry. In this context, IMO assists its Member States in formulating and developing national maritime transport policies (NMTPs), thus strengthening maritime capacities and helping achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. NMTPs are also complementary to the concept of the blue economy, which is closely associated with sustainable development.

What is a National Maritime Transport Policy (NMTP)?

An NMTP is a statement of principles and objectives to guide decisions in the maritime transport sector to achieve the maritime vision of a country and ensure that the sector is governed in an efficient, sustainable, safe and environmentally sound manner. A well-structured and implemented NMTP can give a country the tools it needs to become an effective participant in the maritime sector and harness the full potential of the blue economy.

Training programme for capacity-building activities

To assist developing countries in formulating and enhancing their NMTPs, the Secretariat, in cooperation with the World Maritime University (WMU), developed a training programme and material on preparing, adopting and updating NMTPs. The programme, which combines the material originally prepared in 2015 and the experience gained from delivering such activities in various countries since its inception, was revised and updated in 2021. It is available in English, French and Spanish language. The programme has been developed for use during capacity-building activities in the field of maritime transport policy. It covers topics pertaining to policy rationale, policy formulation and formulation of maritime transport policy, international maritime instruments, and the economic, safety, security, human element and environmental dimension of maritime transport policy formulation. The programme has a broad global dimension and is not country-specific. It explores and encourages discussion on the priorities and challenges in formulating and developing maritime transport policy at the national level. It also discusses the information base and readiness essential to develop and implement such a policy while focusing on meeting global and regional standards.

The programme is primarily designed for maritime administration and ministry of transport officials having different capacities, skills, knowledge and experience in formulating, assessing and implementing maritime transport policy. Officials from other government ministries and agencies would also participate in formulating a maritime transport policy. Prior to the delivery of such activities, countries are required to establish an NMTP Task Force whose role is to promote cross-sectoral participation and facilitate communication at all levels with the ultimate goal of formulating and adopting an NMTP. The training programme consists of a three-day workshop for personnel involved in preparing NMTPs and a one-day seminar for senior transport officials involved in reviewing and adopting NMTPs. The objectives of the training package are twofold:

- • to provide all participants with a standard of knowledge and skills to enable them to understand the major elements of a maritime transport policy and its foundations; and

- • to ensure proper understanding of the obligations of States and the implications of those obligations when formulating maritime policy and legislation on the basis of international maritime treaties.

Vessel Traffic Service (VTS)

A vessel traffic service is a marine traffic monitoring system established by harbour or port authorities, similar to air traffic control for aircraft. The International Maritime Organization defines vessel traffic service as “a service implemented by a competent authority designed to improve the safety and efficiency of vessel traffic and protect the environment. The service shall have the capability to interact with the traffic and respond to traffic situations developing in the vessel traffic service area”. Typical vessel traffic service systems use radar, closed-circuit television, VHF radiotelephony and automatic identification system to keep track of vessel movements and provide navigational safety in a limited geographical area. In the United States, the Coast Guard Navigation Center establishes and operates vessel traffic services. Some services operate as partnerships between the Coast Guard and private agencies.

Personnel

Guidelines require that the vessel traffic service authority be provided with sufficient staff, appropriately qualified, suitably trained and capable of performing the required tasks, taking into consideration the type and level of services to be provided in conformity with the current International Maritime Organization guidelines on the subject.International Association of Marine Aids to Navigation and Lighthouse Authorities Recommendation V-103 is the recommendation sn Standards for training and certification of vessel traffic service personnel. Four associated model courses, V103/1 to V-103/4, are approved by the International Maritime Organization and should be used when training personnel for the vessel traffic service qualifications.

Information service

An information service is a service to ensure that essential information becomes available in time for onboard navigational decision-making. The information service is provided by broadcasting information at fixed times and intervals or when deemed necessary by the vessel traffic service or at the request of a vessel, and may include for example reports on the position, identity and intentions of other traffic; waterway conditions; weather; hazards; or any other factors that may influence the vessel’s transit.

Traffic organization service

A traffic organization service is a service to prevent the development of dangerous maritime traffic situations and to provide for the safe and efficient movement of vessel traffic within the vessel traffic service area. The traffic organization service concerns the operational management of traffic and the forward planning of vessel movements to prevent congestion and dangerous situations and is particularly relevant in times of high traffic density or when the movement of special transports may affect the flow of other traffic. The service may also include establishing and operating a system of traffic clearances or sailing plans, or both, concerning priority of movements, allocation of space, mandatory reporting of movements in the service area, routes to be followed, speed limits to be observed or other appropriate measures which are considered necessary by the vessel traffic service authority.

Navigational assistance is a service to assist onboard navigational decision-making and monitor its effects. The navigational assistance service is especially important in difficult navigational or meteorological circumstances or in case of defects or deficiencies. This service is normally rendered at the request of a vessel or by the vessel traffic service when deemed necessary.

MarineTraffic

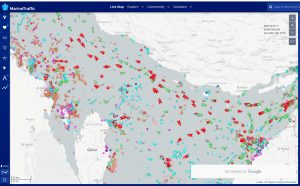

MarineTraffic is a maritime analytics provider, which provides real-time information on the movements of ships and the current location of ships in harbours and ports. A database of information on the vessels includes for example details of the location where they were built plus dimensions of the vessels, gross tonnage and International Maritime Organisation (IMO) number. Users can submit photographs of the vessels which other users can rate. The basic MarineTraffic service can be used without cost; more advanced functions such as satellite-based tracking are available subject to payment. The site has six million unique visitors monthly. In April 2015, the service had 600 000 registered users.

Data is gathered from more than 18,000 AIS-equipped volunteer contributors in over 140 countries worldwide. Information provided by AIS equipment, such as unique identification, position, course, and speed, is then transferred to the main Marine Traffic servers for display via the website in real-time. The site uses data from OpenStreetMap on its base map, and the paid version lets users display ship locations on Nautical Charts.

History

MarineTraffic was originally developed as an academic project at the University of the Aegean in Ermoupoli, Greece. In late 2007, Professor Dimitris Lekkas published it as a trial version.

Community

MarineTraffic is highly dependent on its community of radio amateurs or AIS Station operators, its photographers and translators. In support of the community, MarineTraffic recently made available a free AIS processing tool, under a Creative Commons license.

Marine Traffic in the Persian Gulf, 24.08.2022

Sources: IMO, Wikipedia, Stopford, Martin (1997-01-01). Maritime Economics. Psychology Press. p. 10. ISBN 9780415153102.

“Rank Order – Merchant marine”. CIA.gov. Archived from the original on June 13, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-21.

“The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency”. www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on June 13, 2007.

Almendral, Aurora (December 2018). “Why 10 million Filipinos endure hardship abroad as overseas workers”. National Geographic. United States. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

Marine Traffic

I don’t think the title of your article matches the content lol. Just kidding, mainly because I had some doubts after reading the article.