Discover what to do when a crew member falls overboard through real-life case studies. Learn from past man overboard incidents, best practices, and expert response strategies to improve maritime safety.

Why Man Overboard Response Matters in Maritime Safety

In the vastness of the ocean, the fall of a single person overboard might seem like a small ripple. But for the ship’s crew, it triggers one of the most urgent emergencies at sea. A man overboard (MOB) incident can occur in seconds—whether due to rough seas, human error, or lack of personal protective equipment—and recovering that person safely depends on immediate, coordinated action.

The International Maritime Organization (IMO), through SOLAS regulations and STCW training standards, mandates that all seafarers be trained to respond to MOB events. Yet real-world data shows that survival often depends more on practical readiness and clear communication than on textbook knowledge alone. That’s why studying real-life MOB incidents is so valuable. It reveals how people actually respond under pressure—and where improvements can save lives.

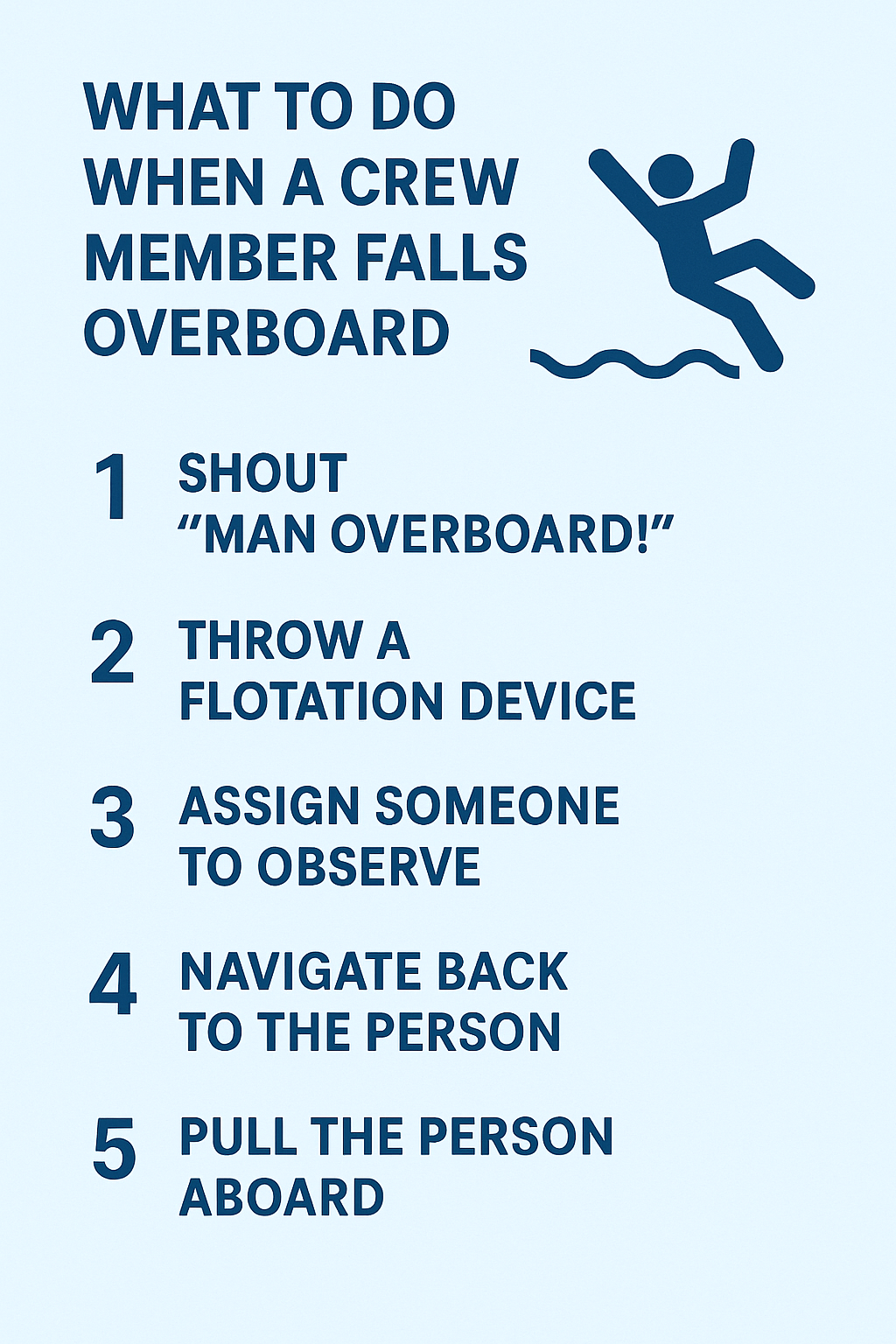

MOB Procedure Overview: What Needs to Happen First

Before diving into the case studies, it’s essential to understand the standard MOB procedure according to SOLAS and best industry practices:

- Raise the alarm immediately. Shout “Man overboard!” and press the MOB button on GPS or ECDIS.

- Mark the location. Deploy a lifebuoy with light and smoke, and begin tracking on the navigation system.

- Initiate a rescue maneuver. Execute a Williamson, Anderson, or Scharnow turn depending on vessel type and sea conditions.

- Inform all personnel. Broadcast internally and externally (VHF Channel 16, GMDSS).

- Launch rescue boats. If conditions allow, deploy the fast rescue craft (FRC) or MOB recovery systems.

- Administer first aid. Once recovered, assess the victim for hypothermia, shock, or trauma.

–

Real-Life Case Study 1: North Sea Cargo Vessel MOB (2022)

Vessel Type: Bulk carrier

Weather Conditions: Night, rough sea state, moderate winds

Outcome: Fatality

During a nighttime deck operation, an able seaman lost balance and fell overboard while trying to secure a loose line. There was no witness, and the alarm was raised only after he failed to report in.

Key Learnings:

- No visual contact meant GPS marking was delayed.

- The lifebuoy light failed during the search.

- Rescue boats were not launched due to harsh conditions.

According to the Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) report, the vessel lacked a motion-triggered MOB detection system, and the crew was unfamiliar with emergency search procedures. The final investigation pointed to inadequate safety drills and poor lighting as contributing factors.

Real-Life Case Study 2: Passenger Ferry in the Mediterranean (2023)

Vessel Type: RoPax ferry

Weather Conditions: Clear skies, moderate swell

Outcome: Successful rescue

A passenger accidentally fell overboard from an upper deck after slipping while taking a photo. A bystander witnessed the fall and immediately alerted crew members.

Key Actions Taken:

- MOB alarm triggered within 30 seconds.

- Two lifebuoys with smoke and lights deployed.

- MOB button used to mark GPS coordinates.

- FRC launched and reached the victim in under 6 minutes.

- Person was wearing a light jacket and remained afloat.

The incident was later highlighted in The Maritime Executive and praised by EMSA for textbook execution of rescue procedures. The ferry’s crew had recently undergone a drill involving a night-time MOB simulation, which significantly improved their preparedness.

Real-Life Case Study 3: Offshore Supply Vessel in the Gulf of Mexico (2021)

Vessel Type: Offshore supply vessel

Weather Conditions: Mild, good visibility

Outcome: Near miss

A crew member fell overboard during cargo transfer while stepping over a slippery area on the deck. He was wearing a personal AIS beacon, which immediately triggered the bridge alarm and GPS alert.

Response Timeline:

- MOB alarm acknowledged instantly.

- AIS location appeared on radar overlay within seconds.

- Rescue team launched FRC with thermal imaging equipment.

- Recovery completed within 8 minutes.

This case became a training model within the DNV MOB Training Program, showcasing the life-saving benefits of wearable technology and regular scenario-based drills. The crew member later said, “If I hadn’t been wearing the beacon, they wouldn’t have found me so fast.”

Real-Life Case Study 4: Fishing Trawler off Alaska (2020)

Vessel Type: Commercial trawler

Weather Conditions: Freezing temperatures, limited daylight

Outcome: Body recovered, fatality

A deckhand fell overboard while hauling nets in icy conditions. Despite being witnessed by another crew member, recovery was delayed due to the vessel’s slow turn and difficulty locating the person in the water.

Challenges Faced:

- Freezing sea caused rapid hypothermia.

- No AIS or thermal gear on board.

- Lifebuoys not deployed quickly enough.

The U.S. Coast Guard investigation concluded that survival window in those waters was less than 15 minutes. Recommendations included upgrading to thermal drones and mandatory insulated PPE in extreme zones.

Technological Tools That Improve MOB Outcomes

AIS MOB Beacons: Compact devices attached to lifejackets or helmets. When immersed, they transmit the person’s location to the ship’s ECDIS system.

Thermal Imaging Cameras: Installed on bridge wings or drones, these devices detect heat signatures even in darkness or fog.

Smart Wearables: Devices like Wärtsilä Guardian or LifeTag auto-activate alarms and GPS marks when submerged.

Man Overboard Detection Systems: Sensors that track rail breaches or camera-based systems that identify sudden movement overboard.

These tools are increasingly being recognized in IMO Maritime Safety Committee circulars and are discussed in publications such as the Marine Pollution Bulletin and WMU Journal of Maritime Affairs.

–

Training Gaps and Human Factors

According to the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS) and The Nautical Institute, the effectiveness of MOB response is still mostly dependent on human readiness. Key gaps include:

- Crew unfamiliarity with MOB buttons or drill timing.

- Underestimation of environmental hazards.

- Poor communication during night or heavy weather incidents.

- Failure to assign MOB-specific roles during pre-departure briefings.

Maritime education centers like Massachusetts Maritime Academy and Maritime Knowledge (India) now include enhanced MOB modules using VR simulators to address real-world stress response.

–

What Makes a Difference in MOB Incidents?

From the above examples, several critical factors emerge:

- Witnessing the fall significantly increases the likelihood of rescue.

- Preparedness and recent drills lead to quicker and more coordinated responses.

- Proper equipment such as functioning lifebuoys, AIS beacons, and thermal imaging are life-saving.

- Environmental conditions are a major determinant of outcome, often beyond control.

FAQs

How long do you have to rescue someone overboard?

Survival time depends on water temperature and weather. In cold water (below 10°C), it can be less than 15 minutes without protection.

Is it required to have MOB detection technology?

Not universally, but IMO encourages its use, and it may be mandatory on certain passenger or offshore vessels per flag state regulations.

Do lifebuoys always help?

Yes, if deployed immediately and correctly. They provide flotation and a visual reference point, especially with lights and smoke.

What kind of drills are most effective?

Scenario-based drills simulating night conditions, rough weather, or multiple MOBs are most effective, especially when followed by debriefs.

Are cruise ships safer in MOB situations?

Cruise ships often have advanced detection systems and trained personnel, but due to their height and speed, recovering someone can still be very difficult.

What is the role of flag states in MOB cases?

Flag states oversee incident investigations and enforcement of SOLAS and STCW standards related to MOB procedures.

Conclusion

Every MOB incident is a reminder that seafaring is still one of the most unpredictable professions. While technology is improving our ability to detect and respond, it is ultimately the crew’s preparedness and the ship’s culture of safety that decide whether a seafarer lives or dies.

These real-world case studies underscore the need for proactive training, real drills, and investment in life-saving gear. From commercial tankers to offshore platforms, every vessel must treat MOB preparedness as a critical priority—not a regulatory checkbox.

Because when someone falls overboard, seconds count. And what you do next could mean everything.

References

- MAIB Reports. https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/marine-accident-investigation-branch

- IMO SOLAS Convention. https://www.imo.org

- EMSA Annual Safety Review. https://www.emsa.europa.eu

- DNV MOB Safety Guide. https://www.dnv.com

- Wärtsilä MOB Tech. https://www.wartsila.com

- The Maritime Executive. https://www.maritime-executive.com

- U.S. Coast Guard Reports. https://www.uscg.mil

- Marine Pollution Bulletin. https://www.journals.elsevier.com/marine-pollution-bulletin

Usually I don’t learn post on blogs, however I would like tto say that this write-up very

compelled me to try and do so! Your writing taste has been amazed me.

Thank you, ery nice post.