Ship maneuvering is a critical aspect of maritime navigation, requiring technical expertise, precise control, and a deep understanding of hydrodynamics. In commercial shipping, maneuvering involves guiding large vessels such as container ships, tankers, and bulk carriers through various maritime environments, including ports, canals, and open seas. The success of these operations depends on the ship’s maneuvering capabilities, weather conditions, and the skill of the bridge team. Ship maneuvering refers to the process of controlling a vessel’s movement through changes in speed, heading, and position. Proper maneuvering ensures safe navigation, collision avoidance, and efficient cargo handling. It requires the use of various control systems such as rudders, propellers, thrusters, and tugboats.

Factors Affecting Ship Maneuvering

Several environmental and operational factors influence a ship’s maneuvering ability:

- Ship Design: Length, draft, beam, and hull shape affect turning performance.

- Weather Conditions: Wind, waves, and current create external forces that can impact the ship’s motion.

- Propulsion System: Types of propellers (fixed-pitch or controllable-pitch) and engine configurations affect maneuverability.

- Rudder Type: Modern ships use high-efficiency rudders such as Schilling rudders for better control.

Types of Ship Maneuvers

The main types of ship maneuvers are categorized based on their purpose, including turning maneuvers, stopping maneuvers, berthing operations, and collision-avoidance maneuvers. Each type involves specific techniques and protocols to ensure safe vessel handling.

1. Turning Maneuvers

Turning maneuvers are essential for changing a ship’s course or direction. These maneuvers are typically performed during navigation through narrow channels, port entry, or ship repositioning.

1.1. Turning Circle Maneuver:A turning circle maneuver determines how sharply a ship can turn when the rudder is fully applied. It is a critical factor during sea trials and is used to assess the ship’s turning characteristics. Key Points:

- Advance: Distance the ship travels forward before completing a turn.

- Transfer: Lateral distance moved from the original course.

- Tactical Diameter: Total distance covered while making a 180-degree turn.

Example: During the sea trials of an oil tanker, the ship’s tactical diameter was measured at 1,200 meters, indicating its turning limitations in confined waterways like the Strait of Hormuz.

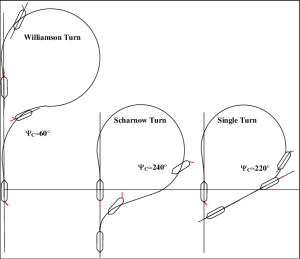

1.2. Williamson Turn:The Williamson Turn is an emergency maneuver used when a man-overboard incident occurs. It involves altering the ship’s course by executing a combination of turns to return to the point of the incident. Procedure:

- Apply hard rudder to one side.

- After 60-70 degrees course change, apply hard rudder in the opposite direction.

- Adjust heading until the vessel is on the reciprocal course.

Case Study: A bulk carrier successfully performed a Williamson Turn after a deckhand fell overboard in the South China Sea, enabling a swift rescue within 10 minutes.

1.3. Crash Stop Maneuver

The Crash Stop Maneuver is an emergency maneuver used to stop a ship in the shortest possible distance. It is employed to avoid collisions or grounding. Procedure:

- Apply full astern propulsion.

- Use rudder for additional steering control if necessary.

- Monitor stopping distance and ship alignment.

Example: A container ship operating near Hamburg Port performed a crash stop to avoid a drifting barge. The vessel stopped within three ship lengths, averting a major collision.

2. Berthing and Docking Maneuvers

Berthing involves maneuvering a ship to a stationary position alongside a dock, pier, or quay. These maneuvers are challenging due to limited space, requiring precise control and tugboat assistance.

Side berthing is the most common docking method where the ship’s side is brought parallel to the quay. Key Techniques:

- Use bow thrusters or tugs to adjust the ship’s position.

- Apply astern propulsion while using rudder angles for directional control.

- Use mooring lines for final adjustments.

Example: The Port of Rotterdam, Europe’s busiest port, handles 200+ berthing maneuvers daily, involving specialized tugboats and advanced docking systems.

2.2. Mediterranean Mooring

In Mediterranean Mooring, the ship is positioned perpendicular to the quay with its stern facing the dock, typically used in small harbors and passenger terminals. Procedure:

- Approach at a slow speed.

- Drop the anchor for added stability.

- Reverse the ship into the docking area using precise helm commands.

2.3. Anchorage Maneuvering

When no berthing facility is available, ships anchor at designated anchorage points. The anchor is dropped while maintaining engine control to prevent drifting. Case Study: A cargo ship awaiting berth clearance at Singapore Anchorage successfully anchored in 25-meter deep water using a calculated chain length ratio of 7:1.

3. Collision-Avoidance Maneuvers

Collision-avoidance maneuvers are essential in congested waterways, where close encounters with other vessels are common.

3.1. Evasive Turn: The evasive turn maneuver helps avoid collisions by altering the ship’s heading using rudder adjustments and speed reduction.

3.2. Zig-Zag Maneuver: The Zig-Zag Test evaluates a ship’s directional stability by applying alternating rudder angles. It is conducted during sea trials to determine the ship’s responsiveness. Example: A cruise ship navigating the Caribbean Sea conducted a zig-zag maneuver to avoid a fishing boat that unexpectedly crossed its course.

4. Canal and Restricted Waterway Maneuvers

Navigating canals like the Suez Canal or Panama Canal requires specialized maneuvering techniques involving tugboats, thrusters, and precision steering. Example: The Ever Given container ship incident in the Suez Canal demonstrated the complexity of maneuvering ultra-large vessels through narrow waterways. High wind conditions and a sudden steering error caused the ship to run aground, blocking global trade for six days.

5. Dynamic Positioning (DP) Maneuvering

Dynamic Positioning (DP) systems use computerized control to maintain a ship’s position without anchoring. Commonly used by offshore support vessels, DP systems rely on GPS, thrusters, and gyroscopic sensors. Example: Offshore drilling platforms and research vessels frequently use DP systems when operating in deep-sea environments where conventional anchoring is impossible.

In conclusion, Mastering ship maneuvering techniques is essential for safe and efficient maritime operations. From turning and docking to collision avoidance, each maneuver requires careful planning, real-time adjustments, and seamless coordination among the bridge team, engineers, and deck crew. Advances in ship design, propulsion systems, and navigation technologies continue to enhance maneuvering efficiency, ensuring safer voyages across the world’s oceans. By understanding the dynamics of various maneuvers, commercial shipping operators can optimize port operations, reduce accident risks, and contribute to the smooth functioning of the global maritime industry.