The Reversal of American Climate Leadership

For decades, the United States has maintained a complicated dual identity in global environmental governance: both as a pioneering voice for climate science and as the world’s most significant historical contributor to the greenhouse gas emissions destabilizing our planetary systems. This contradiction reached its peak when the U.S. officially became the first and only country to formally withdraw from the Paris Climate Agreement not once, but twice—first in 2020 and again in 2025—abdicating its leadership role while retaining its status as the largest cumulative emitter in history. These withdrawals represent more than symbolic political statements; they constitute a fundamental reshaping of global climate governance with far-reaching consequences for ecosystems, international economies, and the collective ability to limit planetary warming to survivable levels.

The strategic retreat of the world’s largest economy from coordinated climate action creates dangerous ripple effects across every dimension of environmental protection. From accelerating sea-level rise that threatens coastal communities worldwide to altering atmospheric chemistry in ways that disproportionately harm vulnerable developing nations, the U.S. withdrawal undermines the foundational principle of common but differentiated responsibilities that has guided international environmental cooperation for decades. This comprehensive analysis examines how America’s climate policy reversals have damaged global ecological systems, impaired oceanic health, created economic headwinds across international markets, and compromised the world’s collective capacity to implement meaningful solutions during a critically narrow window for action.

The Weight of History – America’s Emissions Legacy and Political Instability

The Data of Decline: America’s Enduring Emissions Footprint

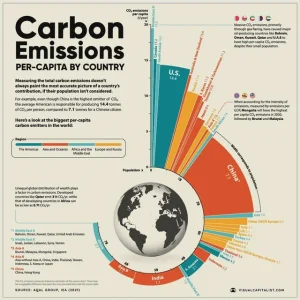

The scale of U.S. historical contribution to atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations establishes both a moral responsibility and practical imperative for American leadership in climate mitigation. With approximately 17% of historic contributions to global warming despite representing only about 4% of the world’s population, the United States has generated an outsized environmental impact spanning generations . Cumulative American CO₂ emissions have reached a staggering 559 gigatons from fossil fuels and land use, establishing the U.S. as the largest cumulative emitter worldwide . This historical context matters profoundly because CO₂ remains in the atmosphere for centuries, meaning that today’s climate disruptions result disproportionately from America’s industrial development and energy choices across the 20th century.

While emissions have decreased by 3.0% since 1990 and approximately 19% since their 2005 peak, this progress remains insufficient against both scientific recommendations and the nation’s own previous climate commitments . The transportation sector has emerged as the largest contributor at 28.4% of 2022 emissions, followed by electric power at 25%, with the latter showing significant improvement due to the transition from coal to natural gas and renewables . This modest decarbonization, however, occurs against a backdrop of persistently high per capita emissions that continue to dwarf those of most other nations. The data reveals a fundamental tension: while the U.S. has demonstrated the technical capacity to reduce emissions while growing its economy, the absolute reduction pace remains incompatible with either its Paris Agreement commitments or the broader objective of limiting warming to 1.5°C.

Credit: https://www.reddit.com/r/newzealand/comments/17yqsb0/carbon_emissions_per_capita_by_country/

The Pendulum Effect: Climate Governance Through Political Cycles

America’s engagement with international climate policy has followed a distinct pattern of advance and retreat closely tied to electoral outcomes, creating what analysts have termed a “pendulum effect” that undermines global climate stability. This pattern began with the U.S. signing but never ratifying the Kyoto Protocol during the Clinton administration, followed by complete non-participation under George W. Bush, reengagement under Barack Obama, withdrawal under Donald Trump, reaccession under Joe Biden, and now a second withdrawal following the 2024 election . This cyclical instability has transformed the United States into an unreliable partner in global environmental diplomacy, with each reversal introducing uncertainty that complicates long-term planning and investment decisions worldwide.

The institutional design of the Paris Agreement specifically accounted for this American political volatility by establishing a one-year waiting period for withdrawal rather than the four-year framework of its predecessor, the Kyoto Protocol . While this design acknowledges political reality, it has proven insufficient to prevent the significant transaction costs associated with repeated U.S. disengagement. As one analysis notes, “The pattern of engagement and disengagement suggests that U.S. climate commitments are contingent on domestic political cycles rather than reflecting a stable, science-based national policy” . This perception has damaged American diplomatic credibility not only in climate forums but across the broader landscape of international cooperation where long-term commitments remain essential.

Table: U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Sector (2022)

| Sector | Percentage of Total Emissions | Key Trends and Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Transportation | 28.4% | Largest emitting sector since 2017; minimal reductions over past decade |

| Electric Power | 25.0% | 35% decrease since 2005 due to shift from coal to natural gas and renewables |

| Industry | 23.0% | Moderate improvements in energy efficiency |

| Agriculture | 9.4% | Significant methane and nitrous oxide emissions |

| Commercial & Residential | 13.2% | Influenced by building efficiency and heating fuels |

| Land Use & Forestry | -13.0% (Sink) | Carbon sequestration through forest growth and other practices |

The Paris Agreement – Understanding US Withdrawal Mechanics and Global Implications

Withdrawal Mechanics and Timeline

The process of American exit from the Paris Agreement follows a carefully defined procedural path that differs significantly between the first and second withdrawals. The initial withdrawal, initiated by the Trump administration in 2019, took effect on November 4, 2020, exactly one year after formal notification to the United Nations . The more recent withdrawal, initiated through an executive order titled “Putting America First in International Environmental Agreements” signed on January 20, 2025, follows a similar timeline but with potentially more permanent consequences . This executive order not only begins the Paris withdrawal process but also immediately ceases “any purported financial commitment made by the United States under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change” and rescinds the U.S. International Climate Finance Plan established under the Biden administration .

Unlike a complete exit from the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which would represent a more radical decoupling from global climate governance, the U.S. remains party to the underlying framework convention while abandoning its specific commitment to the Paris Agreement . This creates an institutional contradiction whereby America maintains a voice in broader climate discussions while abdicating responsibility for the agreement’s specific emissions reduction and financing mechanisms. The withdrawal terminates U.S. obligations related to Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), transparency frameworks, and climate finance while maintaining theoretical membership in the broader UN climate process . This selective engagement reflects a strategic choice to minimize financial contributions while preserving optionality for future reengagement under more politically favorable conditions.

Global Governance Consequences

America’s exit from the Paris Agreement creates a structural vacuum in global climate leadership that fundamentally alters negotiation dynamics and implementation prospects. The absence of the world’s largest economy and second-largest emitter from the agreement’s framework weakens both the pact’s environmental ambition and its political legitimacy. As noted in one analysis, “The biggest impact lies in the U.S. absence from future negotiations” . This absence means the U.S. cannot actively shape critical decisions related to transparency frameworks, market mechanisms, and financial arrangements being developed to implement the agreement, resulting in rules that may not align with American interests and creating future reentry barriers .

The withdrawal also fractures negotiating blocs that have historically advanced certain climate policy approaches. Specifically, it undermines the cohesion of the Umbrella Group—a coalition of non-EU developed countries including Australia, Canada, Japan, Norway, and others that historically aligned with U.S. positions emphasizing national sovereignty, economic efficiency, and flexibility in emissions reduction approaches . Without American participation, this bloc experiences diminished influence in negotiations with other groups like the European Union and the G77/China coalition, potentially shifting the balance toward approaches that prioritize binding international commitments over national determination . This realignment could produce a climate governance architecture less compatible with American economic interests and political preferences, creating long-term strategic disadvantages for the United States even as it seeks to reduce short-term compliance costs.

Damaged Global Ecosystems – The Environmental Consequences of US Disengagement

Impacts on Global Temperature Goals

The absence of meaningful U.S. climate action represents a potentially decisive factor in the global struggle to limit temperature increase to 1.5-2°C above pre-industrial levels—the Paris Agreement’s central objective. Before the most recent withdrawal, analysis suggested that full implementation of the Inflation Reduction Act and other Biden administration policies could have reduced U.S. emissions to approximately 50% below 2005 levels by 2035 . However, with the repeal of these measures and renewed commitment to fossil fuel development, projections now indicate reductions of only 30% below 2005 levels by that same year . This 20-percentage-point gap represents approximately 1.3 gigatons of additional annual CO₂ emissions by 2035—a quantity comparable to the total emissions of Japan, Germany, and Canada combined.

The atmospheric mathematics of climate change are unforgiving: every ton of CO₂ contributes to temperature increase, and the U.S. failure to achieve its emissions potential creates a collective action problem that other nations cannot easily overcome. As one expert notes, “We used to think … that warming of 2°C was a huge problem, but that if we could stay below that, we could avoid the worst of the damage. We’re now seeing the damages starting today and getting much, much worse” . These impacts—including the record-breaking wildfires and unprecedented hurricane activity observed in recent years—occur at barely more than 1°C of warming, demonstrating the escalating risks associated with even modest temperature increases . The U.S. retreat effectively transfers the burden of compensation to other nations while making the fundamental objective of the Paris Agreement increasingly difficult to achieve through technical or political means.

Ocean Systems and Sea Level Rise

The destabilization of global oceanic systems represents one of the most severe and irreversible consequences of inadequate climate action, with U.S. policy decisions contributing directly to these outcomes. As the driver of sea level rise through thermal expansion and ice sheet melt, greenhouse gas emissions threaten coastal communities worldwide through permanent inundation, increased flooding, saltwater intrusion, and habitat loss . The scientific consensus indicates that reducing emissions is the fundamental prerequisite for slowing the pace of sea level rise, making American disengagement from climate mitigation particularly damaging to coastal nations and communities .

The U.S. retreat from climate leadership also undermines critical adaptation efforts in vulnerable regions worldwide. Through mechanisms like the Green Climate Fund and bilateral climate partnerships, American financial and technical resources have historically supported coastal resilience projects ranging from mangrove restoration in Southeast Asia to climate-smart infrastructure in Small Island Developing States . The cessation of these contributions—as mandated by the “Putting America First” executive order—diminishes implementation capacity precisely when accelerating adaptation has become most critical . This creates a double burden for vulnerable nations: they face more severe climate impacts due to elevated emissions while simultaneously losing resources needed to adapt to those impacts.

Table: Projected U.S. Emissions Trajectory Under Different Policy Scenarios

| Policy Scenario | Projected Reduction Below 2005 Levels by 2035 | Key Policies Included | Global Warming Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Trump Policies | ~50% | Inflation Reduction Act, Clean Energy Tax Credits | Aligns roughly with 2°C pathway |

| Current Rollbacks | ~30% | Paris withdrawal, IRA repeal, fossil fuel development | Inconsistent with 2°C or 1.5°C goals |

| Enhanced Ambition | 61-66% (Biden NDC) | Clean electricity standards, electric vehicle mandates | Nearly aligns with 1.5°C pathway |

Global Economic and Equity Impacts – The Ripple Effects of American Retreat

Climate Finance and Development Consequences

The U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Agreement creates a significant financing gap in international climate action that neither other developed nations nor the private sector can easily fill. Under the Biden administration, U.S. international climate finance had increased to over $11 billion annually by 2024, representing a substantial contribution to the $100 billion per year commitment made by developed nations . The termination of these financial commitments—explicitly mandated in the 2025 executive order—forces developing nations to scale back climate ambitions or accept less favorable financing terms that may increase debt burdens or delay implementation . This withdrawal of support particularly impacts nations already experiencing climate stress despite minimal historical contribution to the problem.

The economic repercussions extend beyond direct climate finance to include lost economic opportunities in emerging clean energy markets. Analysis cited by CNN indicates that the Paris Agreement framework created investment opportunities estimated to be worth $23 trillion in the 21 top emerging market economies through 2030 alone . American disengagement threatens to marginalize U.S. companies from these rapidly growing markets while ceding leadership to Chinese, European, and other competitors who maintain commitment to the agreement’s implementation . This represents a significant strategic economic miscalculation that may undermine long-term American competitiveness in the very industries that will define 21st-century technological leadership, from renewable energy deployment to electric vehicle manufacturing and grid modernization.

Equity and Justice Implications

The distribution of climate impacts reflects and exacerbates existing global inequalities, with the consequences of U.S. policy decisions falling disproportionately on vulnerable populations who bear least responsibility for causing the crisis. This creates what climate justice advocates term a double injustice: those who have contributed least to greenhouse gas emissions experience the most severe consequences while having the fewest resources to adapt . The U.S., as the largest historical emitter, bears particular responsibility for addressing this imbalance, making its withdrawal from the Paris Agreement not merely a policy change but an abrogation of moral responsibility.

The American retreat also strengthens the negotiating position of developing country blocs like the G77/China coalition, which may leverage the U.S. absence to advance more aggressive demands for climate finance, technology transfer, and historical reparations . While potentially empowering developing nations diplomatically, this dynamic risks producing a more polarized and less effective climate regime characterized by North-South confrontation rather than cooperation . The carefully constructed compromise embedded in the Paris Agreement—which balanced developed and developing country interests through its system of nationally determined contributions—thus unravels in ways that may ultimately disadvantage all parties, including the United States.

Subnational and Private Sector Responses – The Resilience of Distributed Action

State, Local, and Corporate Climate Leadership

Despite federal retreat, subnational actors across the United States have demonstrated remarkable commitment to climate action, creating a decentralized network of initiatives that partially compensates for federal absence. Following the first U.S. withdrawal from the Paris Agreement in 2017, thirty states and numerous cities committed to uphold the agreement’s objectives through continued emissions reduction efforts . States like California and New York have implemented comprehensive programs to slash emissions through renewable energy standards, carbon pricing mechanisms, vehicle electrification incentives, and building efficiency codes . This distributed leadership creates important demonstration effects and helps maintain technical capacity for future federal reengagement.

The private sector has similarly advanced climate action independent of federal policy, with major corporations committing to science-based targets and 100% renewable energy procurement. This corporate mobilization reflects both recognition of physical climate risks and understanding of the significant economic opportunities represented by the global transition to clean energy. As one analysis notes, by leaving Paris, the U.S. forfeits a huge economic investment opportunity estimated to be worth $23 trillion in emerging markets alone . This economic reality has driven continued private investment in decarbonization even amid federal policy uncertainty, though the absence of coherent national policy creates inefficiencies and limits the scale and pace of transformation.

International Reactions and Compensatory Mechanisms

Other nations have responded to American withdrawal with both condemnation and renewed determination, creating new alliances and implementation mechanisms that partially compensate for the loss of U.S. participation. Following the initial 2017 withdrawal announcement, countries including France, Germany, and Italy indicated they would increase their climate efforts despite American absence . Similarly, in July 2024, China and the European Union committed to collaborating on climate mitigation, referring to the Paris Agreement as “the cornerstone of global climate cooperation” . This realignment strengthens Sino-European influence over the evolving rules and standards of global climate governance, potentially creating frameworks that prioritize their economic and regulatory preferences.

The international community has also developed innovative financing mechanisms and implementation partnerships that bypass traditional nation-state channels. These include the Coalition of Finance Ministers for Climate Action, the International Solar Alliance, and numerous bilateral climate partnerships between individual countries, subnational governments, and private sector entities. While these distributed efforts cannot fully compensate for the absence of the world’s largest economy, they demonstrate the resilience and adaptability of global climate governance in the face of American withdrawal. This institutional resilience suggests that while U.S. disengagement slows global progress, it has not halted the fundamental restructuring of energy systems and economic models underway worldwide.

Pathways Forward – Recommendations for Restoring American Climate Leadership

Near-Term Damage Mitigation Strategies

In the absence of federal leadership, several strategic approaches can help mitigate the most severe consequences of U.S. Paris Agreement withdrawal. First, congressional action could establish certain climate provisions as permanent law rather than executive policy, creating greater policy stability across administrations. Second, state-level initiatives can be strengthened and coordinated through mechanisms like the U.S. Climate Alliance to maximize their collective impact and demonstrate continued American commitment at subnational levels. Third, private sector leadership should be amplified through voluntary emissions reporting, corporate procurement standards, and industry-specific decarbonization partnerships that maintain momentum despite regulatory rollbacks.

Internationally, the United States could maintain certain forms of technical cooperation and scientific collaboration even while outside the Paris framework, including through continued participation in research initiatives, technology sharing programs, and sector-specific agreements. These “mini-lateral” approaches—focusing on specific issues like methane reduction, clean energy innovation, or deforestation—could preserve important elements of climate cooperation even amid broader political disagreement. Finally, American civil society organizations, universities, and philanthropic foundations can help maintain global connections by facilitating knowledge exchange, supporting implementation capacity in developing countries, and documenting both the costs of disengagement and benefits of climate action.

Long-Term Reengagement Framework

The eventual return of the United States to full participation in the global climate regime remains both necessary and probable given the increasing economic and security imperatives of climate action. When political conditions permit, several structural reforms could help insulate future climate policy from electoral volatility while restoring American credibility. These include seeking congressional ratification of future climate agreements to establish greater legal permanence, creating bipartisan commission structures to develop climate solutions with longer time horizons, and implementing automatic policy triggers that maintain certain mitigation activities regardless of political changes.

To accelerate emissions reductions once reengagement occurs, future administrations should prioritize sector-specific strategies targeting the highest-emitting components of the American economy. The transportation sector—now the largest source of U.S. emissions—requires comprehensive transformation through vehicle electrification, investment in public transit, and community redesign that reduces travel demand . Similarly, the building sector needs accelerated efficiency improvements and electrification, while industry requires development and deployment of next-generation technologies like green hydrogen and carbon capture for the hardest-to-abate processes. These technical transformations must be complemented by just transition mechanisms that support workers and communities affected by economic restructuring, building broader political support for sustained climate action.

Conclusion: Our Shared Future in the Balance

The American withdrawal from the Paris Agreement represents more than a diplomatic disagreement or policy divergence; it constitutes a fundamental failure of intergenerational responsibility that will reverberate through ecosystems, economies, and societies for decades. As the largest historical contributor to atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations, the United States bears particular responsibility for leading the global response rather than obstructing it. The consequences of this retreat extend from coral reefs bleaching in warming oceans to coastal communities inundated by rising seas, from agricultural systems disrupted by changing precipitation patterns to public health systems overwhelmed by heat stress and vector-borne diseases.

Yet the story remains unfinished. The same institutional flexibility that enables American withdrawal also facilitates future reaccession, creating the possibility for rapid policy reversal under subsequent administrations. Meanwhile, the distributed leadership of states, cities, corporations, and civil society demonstrates the resilience of climate commitment even amid federal obstruction. The accelerating technological revolution in clean energy continues to reshape economic fundamentals regardless of political resistance. These factors suggest that while American withdrawal has damaged global climate prospects, it has not predetermined the ultimate outcome.

The coming decade will decide whether humanity can avert the most catastrophic climate scenarios and build a prosperous, equitable zero-carbon future. In this decisive period, the world’s most influential nation has temporarily abandoned its leadership role, creating unnecessary headwinds during a critically narrow window for action. Nevertheless, the fundamental drivers of the clean energy transition—technological innovation, economic opportunity, and growing public demand—continue to advance. The ultimate impact of American withdrawal will be determined not only by the duration of federal obstruction but by how effectively other actors—both within the U.S. and internationally—compensate for this absence through redoubled commitment to our planetary future.

Trump is accelerating collapse of western dominance…