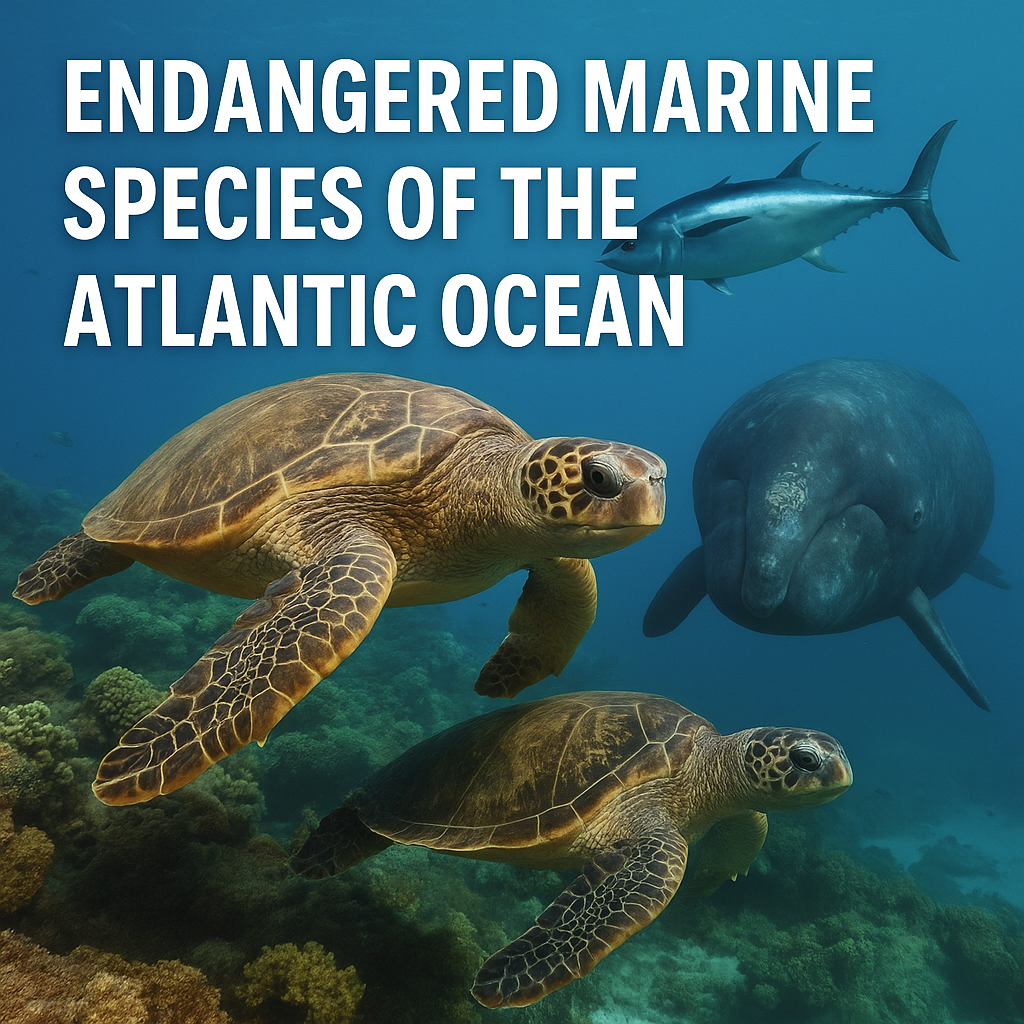

Explore the endangered marine species of the Atlantic Ocean and learn about the urgent conservation actions being taken. This guide blends science, maritime policy, and real-world stories.

Explore the endangered marine species of the Atlantic Ocean and learn about the urgent conservation actions being taken. This guide blends science, maritime policy, and real-world stories.

The Atlantic Ocean, stretching from the icy currents of the Arctic to the warm waters of the tropics, is one of Earth’s most biologically rich regions. Yet, beneath the waves, many marine creatures are fighting for survival. From the iconic North Atlantic right whale to lesser-known deep-sea corals, the Atlantic’s endangered species tell a sobering story of climate change, overfishing, plastic pollution, and habitat degradation.

Understanding and protecting these species is not just a matter of biodiversity—it’s vital for the balance of marine ecosystems, global fisheries, and even coastal economies. In this article, we examine the scope of endangerment, regulatory actions, real-world success stories, and what maritime professionals and policymakers can do to help.

Why Endangered Marine Species Matter to Maritime Stakeholders

In maritime operations, we often focus on vessels, cargo, and ports. But the ecosystems surrounding these activities are increasingly vulnerable. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) and IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) highlight how marine biodiversity supports everything from fisheries and carbon sequestration to coastal protection and maritime tourism.

When species disappear, the impacts ripple across these services. For example:

- A reduction in apex predators like sharks disrupts food webs.

- Coral reef degradation affects fisheries and island communities.

- Marine mammals like whales influence carbon cycles and eco-tourism industries.

The survival of marine species is not a niche environmental issue—it’s connected to global maritime sustainability.

The Most Endangered Marine Species in the Atlantic

North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalaena glacialis)

Fewer than 350 individuals remain. Once hunted to near extinction, today’s threats include entanglement in fishing gear and vessel strikes. According to NOAA and the Marine Pollution Bulletin, up to 85% of right whales show signs of past entanglement.

Maritime regulations now require speed restrictions in key areas during migration season, particularly along the U.S. and Canadian coasts.

Atlantic Bluefin Tuna (Thunnus thynnus)

While not as critically endangered as it once was, bluefin tuna remains under pressure from overfishing. Due to its high value in international markets, particularly Japan, illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing still poses major risks.

The ICCAT (International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas) has implemented stricter quotas and tracking systems in recent years, contributing to signs of recovery.

Nassau Grouper (Epinephelus striatus)

Once abundant across the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico, this reef predator is now critically endangered due to spawning aggregation fishing. Marine reserves and seasonal closures have shown some local success.

Hawksbill Sea Turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata)

Known for its striking shell, the hawksbill has been severely impacted by the global tortoiseshell trade, coastal development, and plastic ingestion. Despite global CITES protections, habitat loss continues across the Atlantic basin.

Deep-Sea Coral Species

The cold, dark depths of the Atlantic host ancient coral reefs, such as Lophelia pertusa, which grow slowly and are extremely vulnerable to bottom trawling. These corals are vital nurseries for fish and invertebrates.

According to the World Ocean Review, many of these deep-sea habitats remain uncharted, underscoring the urgency of marine spatial planning.

Shortfin Mako Shark (Isurus oxyrinchus)

One of the fastest sharks in the ocean, the shortfin mako has seen rapid declines due to bycatch and high demand for fins. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) added the species to its Appendix II list in 2019, requiring strict export controls.

Key Drivers of Marine Species Endangerment in the Atlantic

Industrial Fishing and Bycatch

Large-scale fisheries often use gear like longlines and bottom trawls, which unintentionally capture non-target species. According to the FAO and ICES, bycatch rates for some Atlantic fisheries exceed 20%.

Recent developments include:

- Circle hooks to reduce turtle bycatch

- Acoustic pingers to warn marine mammals

- Real-time fishing closure zones (e.g., Canada’s dynamic management for right whales)

Marine Traffic and Ship Strikes

Increased shipping traffic has made ship strikes a leading cause of death for large marine animals like whales and turtles. The IMO’s voluntary speed reduction zones and mandatory routing measures aim to reduce this risk.

Advanced AIS tracking and predictive modeling tools (from sources like MarineTraffic and Clarksons Research) are now being used to avoid sensitive areas.

Climate Change

Rising ocean temperatures and acidification are shifting the ranges of species and degrading critical habitats like coral reefs and seagrass meadows. Some fish stocks are migrating northward, challenging traditional fishing zones and conservation plans.

Plastic and Chemical Pollution

Microplastics are now found in 100% of sampled Atlantic fish species, according to the Marine Pollution Bulletin. Toxic pollutants such as mercury and PCBs also bioaccumulate in apex predators, threatening reproductive success.

IMO’s MARPOL Annex V addresses garbage and plastic discharge, but enforcement remains a challenge in open waters.

Habitat Loss from Coastal Development

Mangroves, estuaries, and salt marshes—key breeding and nursery grounds—are increasingly cleared for ports, tourism, and industry. As reported by ESPO and UNCTAD, many ports are now investing in ecological buffers and restoration as part of their ESG goals.

Case Studies and Real-World Solutions

Canada’s Protection of the North Atlantic Right Whale

Following a surge in whale deaths in 2017, Transport Canada implemented seasonal vessel speed limits in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. DFO also expanded surveillance with drones and acoustic sensors. These measures have significantly reduced confirmed strikes.

Spain’s Marine Natura 2000 Network

Spain has designated over 8 million hectares of Atlantic waters as part of the EU’s Natura 2000 network, including areas for dolphins, loggerhead turtles, and seabirds. Local fisheries have adopted exclusion zones and seasonal restrictions.

Caribbean Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)

Efforts by countries like Belize, the Bahamas, and Barbados have led to networks of MPAs that protect coral reefs, turtles, and groupers. According to IUCN data, countries that actively enforce MPAs show 25–40% higher fish biomass compared to unprotected zones.

Deep-Sea Trawling Bans in the NE Atlantic

The OSPAR Commission and the EU have enforced bans on bottom trawling below 800 meters in parts of the Northeast Atlantic. This has given hope to deep-sea coral and sponge ecosystems.

Technology and Monitoring for Conservation

Recent developments are helping identify and track endangered species more effectively:

- Satellite tagging: Used for whales, turtles, and sharks; data shared via platforms like Argos and Ocean Tracking Network

- eDNA sampling: Environmental DNA helps identify species present without capturing them

- AIS + AI systems: Companies like Inmarsat and Thetius are using vessel tracking plus AI to predict conflict zones between ships and marine animals

- Blockchain for fisheries: Ensures traceability and reduces IUU fishing, supported by companies like IBM and WWF

Challenges and Ongoing Gaps

Despite successes, challenges remain:

- Enforcement of MPAs in high seas remains limited due to jurisdictional gaps.

- Funding for monitoring programs is inconsistent, especially in developing Atlantic nations.

- Coordination across countries is often hindered by differing regulations and capacities.

The IMO, through its GloLitter Partnerships Project, and the FAO’s ABNJ (Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction) Program aim to fill some of these gaps.

What Maritime Stakeholders Can Do

- Support slow steaming and rerouting in known whale zones

- Reduce plastic waste onboard; use MARPOL-compliant waste systems

- Implement gear modifications to prevent bycatch

- Use real-time biodiversity data to inform navigation and anchoring

- Participate in industry coalitions such as the Clean Shipping Alliance and Global Ghost Gear Initiative

FAQ

What is the most endangered marine species in the Atlantic?

The North Atlantic right whale is considered the most endangered, with fewer than 350 individuals left.

How does shipping traffic impact marine animals?

High-speed vessels can collide with whales and turtles. Noise pollution also disrupts migration and communication.

Are there protected marine zones in the Atlantic?

Yes. Multiple countries have designated MPAs. The EU’s Natura 2000 and the OSPAR network are key regional efforts.

How effective are plastic bans on saving marine life?

While bans on single-use plastics help, enforcement and global ocean currents make it difficult to contain plastic pollution.

Can technology help protect endangered marine species?

Yes. Tools like satellite tracking, eDNA, and predictive AI are becoming central to marine conservation.

What role do port authorities play?

Ports are increasingly integrating biodiversity into their ESG frameworks, restoring coastal habitats, and reducing light/noise pollution.

How does overfishing contribute to endangerment?

Overfishing depletes populations directly and disrupts the food web, putting predators and dependent species at risk.

Conclusion

The Atlantic Ocean is both a cradle of marine life and a frontier of human activity. Its endangered species are sentinels—warning us of environmental imbalance, but also pointing the way to more sustainable practices. Through cooperation, technology, and responsibility, the maritime world can become not only a steward of commerce but also a guardian of the oceans.

From ship operators to port planners, everyone in the maritime sector has a role to play. The tide of extinction can be reversed—but only if we act now.

References

- IMO – GloLitter Partnerships

- NOAA – North Atlantic Right Whale Conservation

- Marine Pollution Bulletin

- IUCN Red List

- UNCTAD Review of Maritime Transport

- World Ocean Review

- European Environment Agency – Marine Natura 2000

- MarineTraffic – Whale Protection Zones

- ICCAT – Bluefin Tuna Conservation

- ESPO – Environmental Report

- Clarksons Research

- Thetius – Maritime Innovation

- WWF Blockchain Tuna Tracking

- BIMCO – Marine Environment

- OSPAR Commission – Deep Sea Protections

- Argos Satellite Tags

- Inmarsat Maritime Sustainability