Learn step-by-step ARPA target acquisition and monitoring procedures. Master tracking, CPA/TCPA, alarms, and best practices for safer watchkeeping.

The most dangerous traffic situation on a bridge is often not the one that looks dramatic on the radar. It is the one that develops quietly, while the officer of the watch is busy with routine tasks and the tracking list is full of “noise targets.” A fishing vessel appears for a moment, disappears behind sea clutter, then reappears closer. An ARPA alarm sounds, but it is the fifth alarm in ten minutes, so it feels less urgent. This is how good equipment can still lead to bad outcomes—when the bridge team does not have a disciplined, repeatable method for acquiring and monitoring targets.

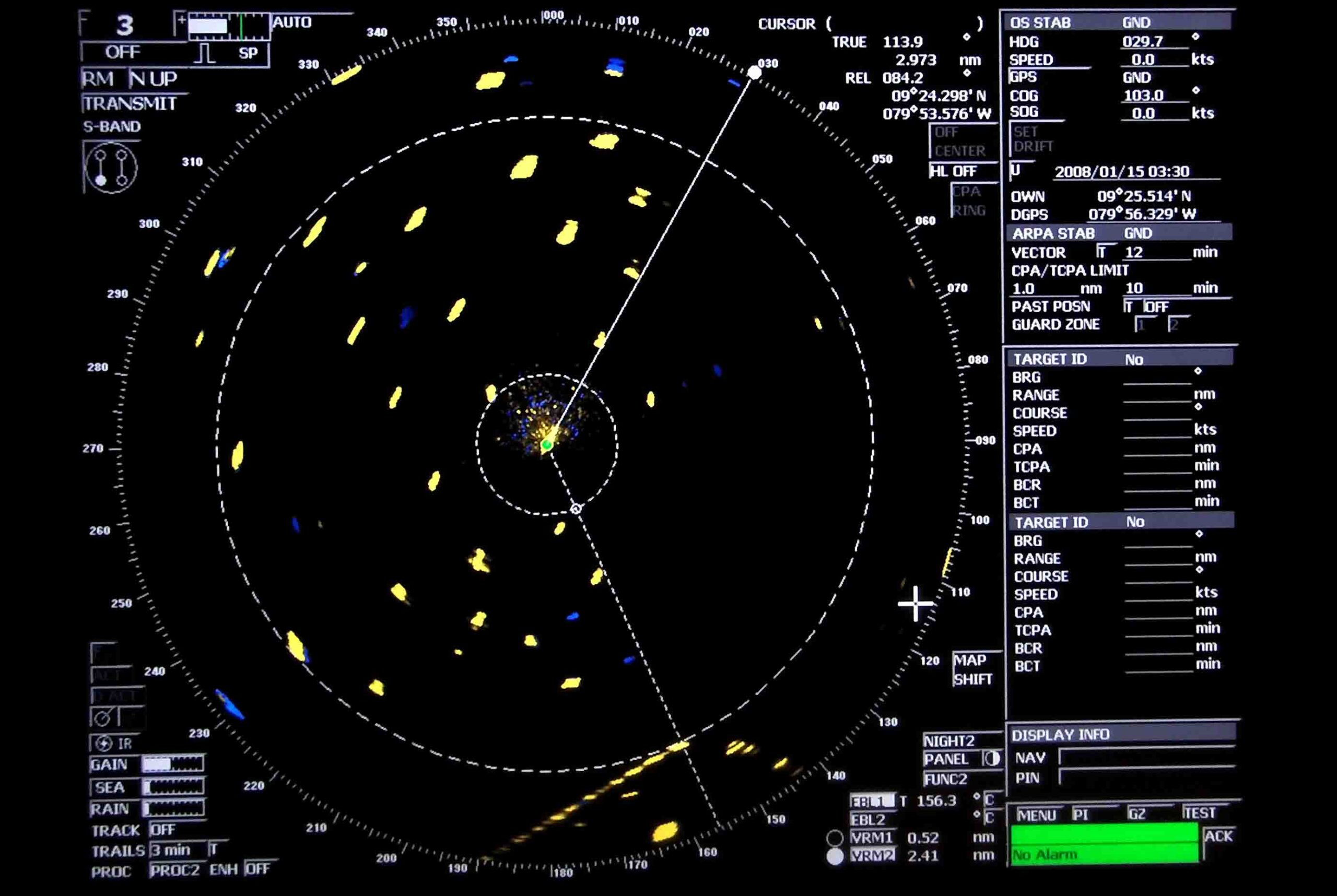

ARPA (Automatic Radar Plotting Aid) is a powerful decision-support tool, but it is not a “magic collision avoidance button.” ARPA performance depends on radar tuning, correct sensor inputs, careful acquisition choices, and continuous monitoring. The goal of this article is to give you a clear, practical, step-by-step procedure you can apply on watch—whether you are a cadet learning the basics or an experienced officer tightening bridge team standards.

Why This Topic Matters for Maritime Operations

Correct ARPA target acquisition and monitoring supports timely risk assessment, reduces missed contacts, and strengthens COLREGs compliance by helping the bridge team evaluate risk of collision using all available means. Under the STCW Convention and Code, officers are expected to demonstrate competence in radar navigation and ARPA use, which includes correct tracking and interpretation of CPA/TCPA trends (International Maritime Organization, STCW framework). In real operations, disciplined ARPA procedures also reduce workload and improve decision quality—especially at night, in restricted visibility, or in high-density coastal traffic.

Key Developments, Technologies, and Principles Behind ARPA Tracking

ARPA Uses Radar Echoes, Not “AIS Data”

A common misunderstanding is that ARPA tracks AIS targets. In reality, ARPA tracks radar echoes—physical returns from objects reflecting radar energy. AIS can be overlaid and correlated, but ARPA’s core tracking is radar-based. This matters because it explains why tuning the radar picture is the first step in any reliable ARPA procedure.

ARPA Needs Time to Stabilise: Early Values Can Be Misleading

When you acquire a target, ARPA calculates course, speed, CPA, and TCPA by observing changes in range and bearing across multiple scans. Early after acquisition, the system has limited history, so vectors and CPA/TCPA can fluctuate. A professional habit is to treat early predictions as “provisional,” then confirm stability before making major manoeuvring decisions.

Sensor Inputs Shape ARPA Quality

Most ARPA systems use inputs from the gyro compass (heading), speed log (speed through water or over ground, depending on configuration), and sometimes GNSS (position, COG/SOG). Incorrect sensor input can produce believable but wrong vectors. A disciplined watchkeeper cross-checks ARPA against the raw radar picture, AIS (when available), and ECDIS context.

The Human Factors Reality: Alarm Fatigue and Over-Tracking

Bridge alarms are meant to help, but frequent nuisance alarms can reduce responsiveness. Over-tracking—acquiring too many low-quality targets—creates alarm overload and weakens the operator’s ability to focus on the few targets that truly define collision risk geometry. Good ARPA procedures are therefore about selecting the right targets and managing them well, not about tracking everything.

Step-by-Step ARPA Target Acquisition Procedures

Step 1: Confirm Your Radar Picture Is “Trackable”

Before acquiring targets, make the radar picture stable and meaningful. If the radar picture is unstable, ARPA tracking will be unstable. Begin by selecting an appropriate range scale for the situation. In coastal traffic, a mid-range such as 6 or 12 nautical miles often provides early detection without losing detail. For close-quarters monitoring, a shorter range such as 3 or 1.5 miles can be used on a second radar or through quick range changes.

Set gain so that weak targets are visible but background speckle is minimal. A practical approach is to increase gain until light noise appears, then reduce slightly until the noise just disappears. Then adjust sea clutter gradually until wave returns are controlled without suppressing small targets near the ship. If rain is present, use rain clutter filtering sparingly and confirm targets by switching ranges and observing whether echoes remain consistent.

This is not a one-time adjustment. On a living sea, conditions change. The officer who expects to tune once and forget is the officer most likely to suffer tracking instability later.

Step 2: Verify Heading and Speed Inputs (The Quiet Source of Big Errors)

Before relying on ARPA vectors, confirm that the radar is receiving correct heading and speed data. A wrong gyro input can rotate vectors and create false CPA/TCPA predictions. A wrong speed input can change relative motion calculations and trial manoeuvre outputs.

A simple habit helps: compare radar heading line stability with the ship’s gyro repeater; verify speed on the radar display matches the conning display; and if available, compare COG/SOG trends on ECDIS with speed log/GNSS. You are not seeking perfection—currents and leeway will create differences—but you are seeking consistency.

Step 3: Decide Your Acquisition Strategy: Manual First, Automation Second

In open water with low traffic, automatic acquisition zones can be useful. In coastal waters, near offshore installations, or in rain clutter, automatic acquisition often creates “garbage tracking.” A strong bridge standard is to default to manual acquisition for targets that matter, and use automatic acquisition only in controlled sectors.

Think of ARPA acquisition like managing a team in an emergency room: you do not want every patient being treated by every doctor simultaneously. You want the right attention on the right cases.

Step 4: Identify the Targets That Actually Define Risk

Before clicking “Acquire,” spend a minute reading the traffic picture. Which targets are on or near your track? Which targets are crossing from the side with steady bearing? Which targets are overtaking or being overtaken? Which targets are near navigational constraints such as shoals, TSS boundaries, or pilot boarding grounds?

The key is to acquire targets that can change your decision-making. A distant vessel diverging away with increasing CPA may not need a dedicated track. A small echo crossing from the starboard bow with a steady bearing probably does.

Step 5: Manual Acquisition: Acquire One Target Correctly, Then Build

When you manually acquire a target, place the acquisition cursor precisely on the radar echo and confirm the correct contact is selected. Avoid acquiring on the edge of clutter or in “multi-echo zones,” where reflections and side lobes may create unstable shapes. If your radar offers target expansion or echo trail display, use it briefly to confirm the echo is consistent.

After acquisition, watch the target for the next several scans. Confirm the tracking symbol remains attached to the echo and does not drift. If the symbol drifts or the target becomes intermittent, do not keep it “for show.” Either retune the radar to stabilise the echo or remove and reacquire once conditions improve.

Step 6: Allow Stabilisation Time Before Trusting CPA/TCPA

ARPA needs time to generate stable vectors. Early after acquisition, the displayed course and speed may fluctuate. A disciplined watchkeeper monitors the trend rather than the first number. If CPA initially shows 0.8 NM but then moves to 1.4 NM after stabilisation, the system is telling you it is still learning the motion.

A practical technique is to keep your first judgement “soft” for the first minute or two, while observing whether the vector settles and whether the raw radar bearing trend matches the predicted behaviour.

Step 7: Set Alarm Thresholds That Match the Navigation Context

ARPA alarms should be meaningful. If your CPA alarm is too conservative in dense traffic, you will get continuous nuisance alarms and lose sensitivity to real danger. If your CPA alarm is too relaxed, you will lose early warning.

Within company procedures, set CPA and TCPA thresholds appropriate to the situation: larger in open sea, smaller in confined waters, and always aligned with manoeuvring room and traffic patterns. The key is not the exact number; the key is that the alarm indicates “a developing problem,” not “normal traffic flow.”

Step 8: Correlate With AIS Carefully, Without Making AIS the “Truth”

If AIS is available, use it to identify the target and confirm general movement. Correlation is helpful, but avoid the common trap of believing that the AIS label guarantees the radar echo identity. AIS can be delayed, misconfigured, or absent. The safest habit is to treat radar/ARPA as the physical detection layer and AIS as the identification layer.

Step 9: Acquire Secondary Targets Strategically

Once your primary risk targets are acquired and stable, add secondary targets as needed. Do not build a tracking list simply because the system allows it. Each tracked target is a promise: you are promising to monitor it.

A healthy bridge standard is to keep the tracking list lean and purposeful. If a target no longer matters, drop it to reduce clutter and alarm load.

Step-by-Step ARPA Target Monitoring Procedures

Step 10: Monitor Trends, Not Snapshots

CPA/TCPA values are predictions based on current motion. They can change quickly if either vessel manoeuvres or if tracking quality changes. The safest way to use CPA/TCPA is to monitor trends over time. Is CPA decreasing steadily? Is TCPA reducing toward a short window? Is the relative bearing remaining steady?

This trend mindset prevents overreaction to single “spike values” and supports earlier, calmer decision-making.

Step 11: Use Raw Radar Behaviour as Your Reality Check

ARPA can be wrong for two main reasons: unstable tracking or incorrect sensor input. Your reality check is the raw radar picture. If the radar echo shows a steady bearing and closing range, but ARPA claims CPA is increasing, you have a discrepancy that must be investigated.

In practice, good watchkeepers occasionally “mute the labels” mentally by focusing on the echo and its motion. This prevents screen-based overconfidence.

Step 12: Watch for Tracking Quality Warnings and Symbol Changes

Most ARPA systems provide indications of tracking quality, target status, or “coasting.” If a target is coasting, the system is predicting position without fresh echo updates. Coasting is not automatically dangerous, but it is a sign that tracking confidence is reduced.

When coasting begins, you should investigate: is the target in sea clutter? Is rain filtering too strong? Has the target merged with another echo? Do you need a range change to separate echoes?

Step 13: Prevent Target Swap During Close Passing Situations

Target swap occurs when two radar echoes pass close together and the ARPA system attaches the tracking symbol to the wrong echo. This can create sudden vector changes and misleading CPA/TCPA.

A reliable prevention habit is to monitor the echo shape and movement during close passing, especially in dense traffic. If vector behaviour suddenly changes without a corresponding change in echo movement, consider target swap and recheck the track.

Step 14: Use Trial Manoeuvre as a Decision Aid, Not a Decision Maker

Trial manoeuvre functions can be extremely useful. They allow you to test course or speed changes and see predicted CPA effects. But trial manoeuvre outputs are only as good as the tracking data and sensor inputs.

Use trial manoeuvre as a way to explore options, then verify by observing whether the raw radar picture and COLREGs logic support the manoeuvre.

Step 15: Keep Bridge Team Communication “ARPA-Literate”

ARPA is a team tool, not an individual tool. Strong bridge teams use consistent language: “Target acquired and stable,” “CPA trending down,” “Target coasting,” “Possible target swap,” “AIS correlated,” “Trial manoeuvre shows CPA 1.5 NM.”

This shared language reduces misunderstanding and keeps everyone aligned—especially during high workload.

Step 16: Document Critical Encounters When Required

In some company procedures and in some pilotage contexts, it is good practice to note significant encounters, including CPA/TCPA at key points and any major manoeuvres taken. This supports post-watch learning and, when needed, incident reconstruction.

The point is not paperwork. The point is building a learning culture where the bridge team can discuss what the system showed and why a decision was taken.

Challenges and Practical Solutions

False confidence is the most common challenge. ARPA can present precise numbers that feel authoritative. The solution is continuous cross-checking with radar, AIS (when appropriate), visual lookout, and ECDIS context.

A second challenge is clutter management. In coastal waters, ARPA can become overwhelmed by buoys, land reflections, and fishing targets. The solution is disciplined acquisition: manually acquire only targets that matter, reduce automatic acquisition zones, and retune the radar to stabilise true echoes rather than “cleaning the screen” aggressively.

A third challenge is alarm overload. If alarm thresholds are set too tight, the bridge team receives constant warnings. The solution is contextual thresholds and purposeful tracking lists. An alarm should feel like information, not background noise.

Finally, fatigue and distraction can degrade monitoring. The solution is procedural rhythm: regular scanning cycles, verbal callouts, and periodic “system checks” of sensor inputs and tracking lists.

Case Studies and Real-World Applications

Many collision investigations share a similar theme: the radar picture contained the necessary information, but the bridge team did not acquire or monitor targets early enough, or did not interpret trends correctly. In several reports, investigators note that targets were visible on radar but not acquired by ARPA, leading to weaker CPA/TCPA monitoring and reduced alarm effectiveness. These cases are rarely about technology failure; they are about procedural discipline and human factors.

On the positive side, professional watchkeeping examples show how early acquisition creates time. When targets are acquired early and monitored calmly, officers have the “luxury of time” to apply COLREGs correctly. Instead of last-minute course alterations, they can make early, obvious manoeuvres that are safer and easier for other vessels to interpret.

Future Outlook and Maritime Trends

ARPA technology continues to improve through better signal processing, clutter discrimination, and integration with bridge systems. The broader e-Navigation direction is toward richer sensor fusion, where radar/ARPA, AIS, ECDIS, and decision-support tools are more tightly combined.

But increased integration creates a new risk: single-source errors that look like multi-source confirmation. If AIS feeds multiple displays, wrong AIS data can appear “validated” across systems. The future bridge therefore needs both better technology and stronger data literacy.

In practical terms, the best future trend is training. More realistic simulator scenarios, including target swap events, sensor failures, and rain clutter episodes, can build officer competence faster than theory alone.

FAQ

How long should I wait before trusting ARPA CPA/TCPA after acquisition?

Allow time for stabilisation. In many situations, one to three minutes of tracking history improves reliability. Monitor trends and confirm against raw radar behaviour.

Should I use automatic acquisition zones all the time?

No. Automatic acquisition is useful in low-clutter environments, but in coastal waters and dense traffic it can create excessive tracked targets and nuisance alarms. Manual acquisition is often safer.

Why do I get frequent “lost target” alarms?

Lost target alarms usually indicate unstable radar echoes caused by clutter, weak targets, or excessive filtering. Improve radar tuning, adjust acquisition strategy, and verify tracking quality.

What is the biggest mistake officers make with ARPA monitoring?

Treating CPA/TCPA as absolute truth instead of predictions. Good watchkeeping uses CPA/TCPA trends, cross-checks with radar echo movement, and applies COLREGs judgement.

How can I detect target swap?

If a tracked target’s vector changes suddenly without a corresponding change in radar echo movement, suspect target swap. Recheck the echo and consider reacquiring the target.

Should I rely on AIS to confirm ARPA targets?

AIS is helpful for identification and context, but it is not a guarantee of target identity or accuracy. Use AIS as a supplement and keep radar/ARPA as your physical detection reference.

What ARPA setting reduces nuisance alarms most effectively?

There is no single setting. The most effective approach is purposeful target acquisition, correct radar tuning, and context-based CPA/TCPA thresholds.

Conclusion and Take-away

Step-by-step ARPA procedures are not about memorising buttons. They are about building a disciplined bridge habit: tune the radar for stable echoes, verify sensor inputs, acquire the targets that matter, allow stabilisation, and monitor trends with continuous cross-checking.

When you apply these procedures consistently, ARPA becomes what it was meant to be: a reliable support for traffic awareness and collision avoidance, not a source of nuisance alarms and confusion. If you are training officers or improving bridge team standards, the best investment is repetition—practise the same acquisition and monitoring rhythm until it becomes natural.

For maritime professionals seeking stronger competence, consider revisiting ARPA procedures in a simulator environment and aligning them with your company’s Bridge Procedures Guide and STCW training outcomes.

References

International Maritime Organization. (n.d.). STCW Convention and Code (overview and framework). https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/HumanElement/Pages/STCW-Conv-LINK.aspx

International Maritime Organization. (1972/updated). Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGs). https://www.imo.org/en/About/Conventions/Pages/COLREG.aspx

International Maritime Organization. (2004). Revised performance standards for radar equipment (MSC.192(79)) (Resolution). https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/KnowledgeCentre/IndexofIMOResolutions/MSCResolutions/MSC.192%2879%29.pdf

International Chamber of Shipping. (Latest edition). Bridge Procedures Guide (publication page). https://www.ics-shipping.org/publication/bridge-procedures-guide/

International Association of Classification Societies. (n.d.). IACS publications and guidance (navigation/bridge systems context). https://iacs.org.uk/publications/

DNV. (n.d.). Maritime safety, human factors, and bridge systems resources (publication hub). https://www.dnv.com/maritime/

Lloyd’s Register. (n.d.). Marine and offshore guidance and publications (bridge equipment and safety topics). https://www.lr.org/en/insights/

UK Marine Accident Investigation Branch. (n.d.). Investigation reports and safety lessons (bridge watchkeeping and collision themes). https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/marine-accident-investigation-branch

United States Coast Guard Navigation Center. (n.d.). AIS, navigation, and safety information (reference library). https://www.navcen.uscg.gov/

National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. (n.d.). The American Practical Navigator (Bowditch). https://msi.nga.mil/Publications/APN