Master marine radar fundamentals with clear guidance on X-band vs S-band. Learn strengths, limits, and best practices for safer navigation in all weather.

Credit:https://www.facebook.com/groups/450918856816986/

It is 03:20 on the bridge. Outside, the sea is black and glossy, and the horizon has vanished into drizzle. The ship is steady, the engine note is constant, and the only “landscape” is the radar screen—bright echoes, faint smudges, and a few confident AIS symbols that look reassuringly precise. In moments like this, radar is not just equipment. It is your sense of sight.

But radar is also a language, and like any language, it can be misunderstood. Officers may assume that “a radar is a radar,” and that the only real skill is turning the range knob and avoiding clutter. In reality, the radar picture you see depends heavily on frequency band, signal processing, antenna characteristics, and how you tune the set for the environment. That is why understanding X-band and S-band is not a textbook exercise—it is a practical safety skill.

This article explains marine radar fundamentals in globally accessible English, focusing on what X-band and S-band do best, what they struggle with, and how to use both intelligently for collision avoidance, coastal navigation, and heavy-weather operations.

Why This Topic Matters for Maritime Operations

Seaborne trade still carries the majority of global goods, and ships are increasingly rerouted by congestion, conflict, climate-driven disruptions, and port variability—meaning more voyages are exposed to unfamiliar waters, heavier traffic, and challenging weather windows. In that environment, radar remains one of the most resilient sensors on the bridge: it works day and night, and it can “see” through many conditions that defeat the human eye. International carriage requirements also make radar a core safety barrier on many vessels, which signals how strongly regulators view radar as essential to safe navigation.

Key Developments, Technologies, and Principles

What Marine Radar Really Measures

A marine radar does not “see ships.” It measures reflections of radio energy and turns them into a picture. Think of it like shining a flashlight into fog—but instead of visible light, you transmit radio waves and listen for what bounces back.

What comes back depends on target characteristics (size, shape, material, aspect angle), sea state (waves create their own echoes), rain and moisture (they can absorb or scatter energy), the radar frequency band, and your tuning choices such as gain and clutter controls. The key point is simple: the radar picture is not a photograph. It is an interpretation of echoes, shaped by physics and settings.

The Two Bands You Meet at Sea: X-band and S-band

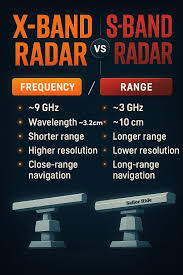

Modern shipborne radars commonly operate in two main frequency ranges: X-band around 9.2–9.5 GHz and S-band around 2.9–3.1 GHz. These bands matter because they behave differently in real conditions.

Higher frequency radar energy (X-band) tends to provide sharper target separation and better detail, which is why navigators often prefer it for pilotage, close-range work, and identifying small features. Lower frequency radar energy (S-band) tends to perform more consistently in heavy rain, fog, and sea clutter, which is why it is valued when conditions become difficult.

A Simple Analogy: Camera Zoom vs All-Weather Lens 📷🌧️

If radar bands were camera lenses, X-band is like a sharp zoom lens that can give crisp detail but may struggle when heavy rain interferes with the “view.” S-band is like an all-weather lens that may not show fine detail as strongly, but keeps working when the environment is trying to blind you.

The practical lesson is that the best bridge teams do not treat X-band and S-band as competitors. They treat them as complementary tools and choose the right one for the moment.

Why Carriage Requirements Mention Specific Radar Bands

Radar carriage requirements distinguish radar expectations by vessel size, and they recognise that vessels may carry a 9 GHz radar and, for certain ships, an additional radar capability at 3 GHz (or a second 9 GHz radar) as a functionally independent installation. Operationally, that matters because a second radar is not only redundancy; it can also be configured differently for different conditions, ranges, and tasks.

Pulse Length, Resolution, and Why X-band Often Looks “Sharper”

Resolution is the radar’s ability to separate two close echoes into two distinct targets instead of one merged blob. It is influenced by pulse length, antenna beamwidth, and signal processing.

In practical watchkeeping language, shorter effective pulses and narrower beams help you pick targets out of clutter and separate them at close ranges. That is why X-band is often chosen for confined waters and traffic situations where detail and discrimination reduce uncertainty.

Solid-State Radar, Pulse Compression, and the Modern Radar Picture

Many vessels now use solid-state radar or hybrid designs that rely on advanced signal processing. Pulse compression can improve short-range performance while maintaining useful energy for detection. This can produce clearer close-range images and better small-target detection—if the operator understands the modes and the trade-offs.

It is important to remember that more processing can also create a more “polished” picture, and a polished picture can sometimes hide weak echoes if filters are applied too aggressively. Skill is not only about getting a clean screen; it is about keeping the information that matters.

Standardized Interfaces: Reducing Confusion

Modern bridge equipment includes deep menus, overlays, and alert logic. Standardized user interface guidance exists because inconsistent controls and symbols increase cognitive load—especially during crew changes, mixed fleets, and high-stress situations. The less time you spend hunting menus, the more time you have for situational awareness.

Understanding X-band vs S-band in Practice

Where X-band Usually Shines

X-band is commonly favoured when you need detail and separation. In coastal navigation and pilotage, it can show clearer land edges, breakwaters, buoys, and small targets—especially at short and medium ranges. In congested waters, it can also help separate two close vessels that might merge into one echo on a less discriminating display.

In day-to-day bridge life, navigators often say X-band “looks better.” The deeper truth is that it often helps you make decisions faster because it reduces ambiguity in the picture—when the environment is cooperative.

Where S-band Usually Shines

S-band is commonly favoured when the environment becomes hostile. Heavy rain can fill an X-band screen with clutter and reduce detection by attenuation. Sea clutter can also dominate close ranges in strong winds. In such moments, S-band often maintains more stable detection and tracking of significant targets, and the coast may remain more consistent on the display when X-band becomes noisy.

If you remember nothing else, remember this: S-band is often the radar that keeps you “seeing” when you most need reliable information.

The “Hidden Truth”: Band Choice Is Often About Avoiding False Confidence

A dangerous habit at sea is believing the clearest picture is always the most reliable picture. X-band can look crisp and reassuring on calm nights. Then a rain band arrives, and the same display can quickly become misleading. Meanwhile, S-band may look less sharp, yet still be telling you the truth.

Band selection is therefore not about aesthetics. It is about reducing false confidence.

Challenges and Practical Solutions

Sea clutter is one of the most common operational problems. It is radar echo from waves, strongest at close ranges, increasing with wind and sea state. When sea clutter grows, weak targets can disappear—especially small craft and low-profile objects. The practical solution is to tune with discipline rather than emotion. A structured approach works better than random knob turning: set gain to a controlled level where background noise is visible but not overwhelming, apply sea clutter controls carefully to calm the near-range snowstorm, and then revisit gain because these controls interact. In heavy seas, it is often sensible to compare the two bands rather than forcing one band to solve every problem.

Rain clutter is different. Rain can create a curtain of echoes and can also reduce detection range by scattering and absorbing energy. The practical solution is to treat rain as both a display problem and a physics problem. Use rain clutter controls to reduce the visual curtain, but do not over-filter, because aggressive filtering can erase weak targets. When rainfall is intense, switching to S-band or placing S-band as the primary picture often restores useful detection when X-band becomes noisy.

Over-filtering is a modern risk. Today’s radars can produce clean screens that feel comfortable, but comfort can be dangerous if it is achieved by deleting information. A good habit is to conduct brief “reality checks.” When workload allows, reduce filtering temporarily and observe what returns appear. If weak echoes suddenly show up, it is a sign your normal settings may be too aggressive for the current conditions. This habit is not distrust; it is calibration.

Installation effects also matter. Blind sectors, shadowing, and antenna height influence what the radar can detect. Masts, cranes, funnels, and container stacks can create shadow arcs. Sometimes one radar has noticeably better coverage than the other. The practical solution is to know your ship’s blind arcs and treat them like local navigational hazards. If the bridge team does not understand them, they may assume an empty sector on the radar means an empty sea—when it may simply mean the antenna cannot “see” there.

Interpretation errors in congested waters remain a major risk. It is possible to detect a target and still misunderstand the collision situation. This is where radar competence becomes more than tuning. It becomes decision-making. The practical solution is structured appraisal: confirm risk by observing bearing drift and range trend, use tracking tools as support rather than as authority, and cross-check with visual information when available. Radar gives you data; judgment turns it into action.

Interface confusion is another challenge, especially when officers change ships frequently. Different brands use different menus and presentation modes. Under stress, small interface mistakes can become large navigational errors. Practical solutions are simple but powerful: standardize display routines where possible, use agreed starting settings for open sea and confined waters, and conduct short familiarization drills after joining—especially drills that involve band switching, clutter tuning, and quick range scale selection.

Finally, interference in busy areas can degrade the radar picture. When many vessels operate radars in the same environment, patterns, streaks, or unusual noise may appear. Practical solutions include adjusting settings, changing modes where available, switching bands, and ensuring persistent issues are logged for technical investigation. Interference is not always “operator error,” but managing it is part of professional watchkeeping.

Case Studies / Real-World Applications

A common pattern in serious casualties is that both vessels detected each other, sometimes by radar and AIS, yet still failed to avoid collision. The lesson is uncomfortable but important: detection is not the same as appraisal. Radar can show you a target clearly, but the bridge team must still interpret movement correctly, understand the rules of the road, and act early enough to be effective. In practice, this means radar training should include decision-making exercises, not only tuning exercises.

Another real-world scenario is heavy rain on approach to a pilot station. In a tropical squall, X-band may become dominated by rain clutter and attenuated returns. The bridge team may feel like the sea has become empty or uncertain at exactly the wrong time. In such situations, using S-band as the primary picture often restores meaningful detection of significant targets and land. The goal is not a perfect picture. The goal is a reliable picture.

A third scenario involves small targets near shore. During coastal navigation, particularly near fishing grounds, buoys, or small craft, X-band detail can be operationally valuable. It can separate echoes that would otherwise merge, reducing uncertainty in close-range maneuvering. When you pair that detail with disciplined tuning and cross-checking, X-band becomes an excellent pilotage tool.

Future Outlook and Maritime Trends

Radar is evolving in three broad directions: more processing capability, tighter integration with other bridge systems, and increasing importance of human-machine interface design. Solid-state and pulse-compression technologies are expanding the performance envelope, especially at short ranges. At the same time, integration with ARPA, AIS, and chart overlays is becoming more common, which can improve situational awareness when used responsibly.

However, the human role will not shrink. In many ways, it will grow. As systems become more capable, the navigator must understand not only what the radar shows, but also what the radar might hide through filtering or limitations. Another growing theme is electromagnetic awareness and reliability: interference management, maintenance discipline, and system checks matter more as more electronic equipment shares the bridge environment.

The future bridge will likely have “smarter” radars, but it will still need mariners with fundamental radar understanding. Technology will assist, but seamanship will decide.

FAQ Section

1) What is the main difference between X-band and S-band marine radar?

X-band usually provides sharper detail and better separation of close targets. S-band is often more reliable in heavy rain, fog, and sea clutter.

2) Which radar is better in heavy rain?

S-band is often better in heavy rain because it tends to maintain more stable detection when precipitation affects higher-frequency signals.

3) Why do ships carry two radars?

Two radars provide redundancy and allow different configurations at the same time. For example, one can be optimized for close-range detail while the other is optimized for weather resilience or long-range scanning.

4) Does a clean radar screen always mean it is correctly tuned?

No. Over-filtering can remove weak targets along with clutter. A good operator checks what the radar is suppressing and adjusts settings as conditions change.

5) Can AIS replace radar?

No. AIS depends on transmissions and correct input data, and not all targets carry AIS. Radar independently detects physical echoes and remains essential.

6) What is the best quick tuning approach for real watchkeeping?

Use a consistent sequence: set gain to show controlled background noise, reduce sea clutter carefully, apply rain clutter cautiously, and re-check gain because the controls interact. Compare X-band and S-band rather than forcing one band to handle all conditions.

7) Why do collisions still happen when both ships detect each other?

Because detection is not the same as appraisal. Collision avoidance depends on correct interpretation of relative motion, compliance with COLREGs, and early, effective action.

Conclusion / Take-away

Marine radar is not one skill—it is a set of linked skills: understanding the physics, selecting the right band for the conditions, tuning with discipline, and interpreting the picture with calm judgment.

If you remember only one principle, make it this: X-band and S-band are complementary, not competing. X-band often gives sharper discrimination and detail; S-band often keeps working when rain and sea clutter are trying to blind you.

For learners and bridge teams, the safest habit is to practice in normal conditions so you are ready in abnormal ones. Use both radars intentionally, cross-check what you see, and treat the radar picture as a conversation with the sea—not a simple photograph.

Soft call-to-action: Add short radar drills to routine training—band switching in rain, clutter tuning in heavy seas, and quick collision-risk appraisal exercises. Small practice sessions build the muscle memory that saves time when minutes matter.

References

-

American Bureau of Shipping. (2024). Guide for bridge design and navigational equipment/systems. https://ww2.eagle.org/content/dam/eagle/rules-and-guides/current/conventional_ocean_service/94-guide-for-bridge-design-and-navigational-equipment-systems-2024/94-bridge-design-guide-dec24.pdf

-

International Electrotechnical Commission. (2013). IEC 62388: Shipborne radar—Performance requirements, methods of testing and required test results. https://webstore.iec.ch/en/publication/6967

-

International Maritime Organization. (2004). Resolution MSC.192(79): Adoption of the revised performance standards for radar equipment. https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/KnowledgeCentre/IndexofIMOResolutions/MSCResolutions/MSC.192%2879%29.pdf

-

International Maritime Organization. (2019). Guidelines for standardized user interface design for navigation equipment (MSC.1/Circ.1609). https://wwwcdn.imo.org/localresources/en/OurWork/Safety/Documents/IMO%20Documents%20related%20to/MSC.1-Circ.1609.pdf

-

Marine Accident Investigation Branch. (2014). CMA CGM Florida and Chou Shan—Serious marine casualty report. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/547c6f36e5274a4290000017/CMACGMFlorida_Report.pdf

-

National Telecommunications and Information Administration. (2021). Solid-state marine radar interference in magnetron marine radar environments. https://its.ntia.gov/publications/download/TR-21-556.pdf

-

UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (n.d.). Review of Maritime Transport—Topic page and key statistics. https://unctad.org/topic/transport-and-trade-logistics/review-of-maritime-transport

-

UK Government. (n.d.). SOLAS Chapter V – Safety of Navigation (consolidated text). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7f0081ed915d74e33f3c6e/solas_v_on_safety_of_navigation.pdf

-

Wang, X., et al. (2023). Radar signal behavior in maritime environments: Effects of falling rain. Electronics, 13(1). https://www.mdpi.com/2079-9292/13/1/58