Master Radar ARPA for safe navigation. This guide explains CPA, TCPA, vectors, and proper use to avoid collisions, with real case studies and future radar trends for officers.

For centuries, a mariner’s greatest fear in fog or darkness was the sudden, ghostly echo on the radar screen—an unseen vessel on a potential collision course. The frantic manual plotting of its position every few minutes, the slide-rule calculations of speed and course, and the tense uncertainty defined old-school radar watchkeeping. Today, that critical task is transformed by a powerful digital ally: the Automatic Radar Plotting Aid (ARPA). Mandated on most commercial bridges, ARPA is not just a radar display; it is a predictive collision avoidance system. It automatically tracks targets, calculates their motion, and presents the officer with clear, actionable data to make safe navigation decisions. However, this powerful tool is often misunderstood or misused, leading to over-reliance and tragic consequences. This article demystifies ARPA, moving from its core principles to advanced practical application, ensuring you can harness its power while respecting its limitations to become a more confident and competent watchkeeper.

Why Mastering ARPA is Non-Negotiable for Safe Navigation

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) requires ARPA on all ships of 10,000 gross tonnage and upwards, and it is considered essential equipment under the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS). This mandate reflects a simple, critical truth: in congested waterways, poor visibility, and complex traffic situations, the human brain alone cannot reliably and continuously process the raw radar data of multiple moving targets. ARPA performs this continuous computation flawlessly, providing the Officer of the Watch (OOW) with processed information that would be impossible to derive manually in real-time. Its purpose is to enhance situational awareness and provide early warning of developing risks, directly supporting compliance with the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGs). However, as investigated in numerous incidents by the UK Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) and National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), accidents still occur when officers treat ARPA outputs as absolute truth rather than intelligent aids. Therefore, true mastery is not about pushing buttons; it’s about understanding the system’s logic, correctly interpreting its outputs, and integrating that information with visual lookout, AIS data, and sound seamanship. It is a fundamental professional competency for the modern maritime world.

From Manual Plotting to Automatic Tracking: The Core Principles of ARPA

To appreciate ARPA, one must first understand the problem it solves. Traditional radar shows only the current position, or “echo,” of a target. To determine if it is a collision threat, a mariner must manually plot its position over several minutes on a reflection plotter, draw a line through these plots to find its true course, measure its speed, and then calculate its future trajectory relative to your own ship. This process is time-consuming, prone to error, and impractical for tracking more than one or two targets.

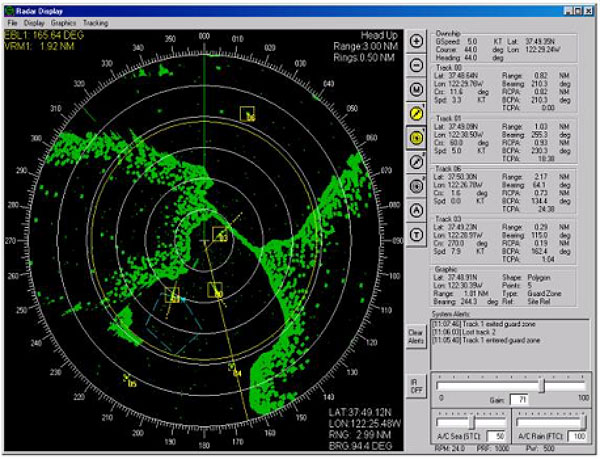

ARPA automates this entire process. Once a radar target is manually or automatically “acquired” by the operator, the ARPA system begins tracking it. It uses sophisticated algorithms to monitor the target’s changing range and bearing over time. From this raw data, it computes the target’s:

-

True Course (the direction it is moving over the ground).

-

True Speed.

-

Closest Point of Approach (CPA): The minimum distance between your vessel and the target, assuming both maintain current speed and course.

-

Time to Closest Point of Approach (TCPA): How many minutes until the CPA occurs.

This data is continuously updated and displayed right on the radar screen, typically next to a vector line (graphical arrow) emanating from the target. This vector visually represents the target’s computed course and speed. The real genius of ARPA is its ability to do this for dozens of targets simultaneously, providing a complete, real-time picture of the traffic situation.

Understanding the Language of ARPA: Vectors, CPA, and TCPA

The primary outputs of ARPA—vectors, CPA, and TCPA—form the essential language of collision avoidance.

Vectors are the graphical arrows on the screen. They can be displayed in one of two modes: True Vectors or Relative Vectors.

-

True Vectors show the true motion of all tracked targets relative to the ground (or water, depending on settings). They indicate where each target is actually going. On a true-motion display, your own ship’s vector will also be shown, moving across the screen.

-

Relative Vectors show the motion of all targets relative to your own ship. In this mode, your ship is stationary at the center of the display. A relative vector points directly at the predicted point of collision. If a target’s relative vector line passes through the center of your screen (your position), it is on a collision course, provided both vessels maintain speed and course.

CPA and TCPA are the numerical guardians. The officer sets guard limits—a minimum acceptable CPA (e.g., 1.0 nautical mile) and a TCPA threshold. If the ARPA calculates that a tracked target will breach these limits, it triggers both a visual and an audible alarm. This is the system’s primary function: to provide an early, unambiguous warning of a developing risk, giving the OOW ample time to assess the situation, determine the proper action under COLREGs, and execute a safe maneuver.

The ARPA Workflow: Acquisition, Tracking, and Interpretation

Effective use of ARPA follows a disciplined workflow. The first step is target acquisition. In automatic acquisition mode, the system will acquire targets within a defined area around your ship. However, most experienced officers recommend manual acquisition for critical targets. This ensures you are actively selecting and monitoring the vessels that pose the most immediate or complex risk, rather than relying on the computer’s logic, which might prioritize a large, distant ship over a small, fast-approaching craft.

Once acquired, the target enters the tracking phase. It is crucial to understand that ARPA needs time—typically 30 seconds to one minute—to establish a stable track. Initial vectors and CPA/TCPA data during this period can be erratic and unreliable. The officer must wait for the tracking to stabilize before trusting the data. The system display will usually indicate the “track status,” often with codes like “TRK” for a stable track.

The final and most critical step is interpretation. The officer must synthesize the ARPA data:

-

Check the vector mode. Are you looking at true or relative vectors? Misinterpreting this is a classic error.

-

Analyze the CPA/TCPA. Is it safe and comfortable? Is it decreasing or increasing?

-

Observe the trend. Watch how the vector lines and CPA/TCPA values change over time. A small, steady change might indicate a slow maneuver by the other vessel. A sudden shift could signal a radar echo from a different part of a large ship (called “target swap”) or an actual radical maneuver.

-

Cross-check with other sources. Never rely on ARPA alone. Correlate the target with a visual sighting, its AIS data (if available), and use radar observations (like checking the target’s aspect by its echo shape) to build a complete picture.

Common ARPA Pitfalls and Operational Challenges

ARPA is a powerful aid, but it is not infallible. Awareness of its limitations is what separates a competent user from a vulnerable one.

-

Garbage In, Garbage Out: ARPA’s calculations are only as good as the radar data it receives. Poor radar tuning, sea clutter, rain clutter, or radar interference can corrupt the echo, leading to unstable tracks and false vectors. The system cannot track what it cannot see clearly.

-

The Target Swap: This is a major source of error. When two targets pass close to each other, the ARPA tracking logic can mistakenly “jump” the track from one target to the other. Suddenly, the data for “Target A” is now attached to “Target B,” producing dangerously misleading vectors and CPA information. Vigilant observation is required when targets are in close proximity.

-

Over-Reliance and Complacency: The most dangerous pitfall is the “watch-the-screen” mentality. ARPA can create a false sense of security, leading officers to fixate on the digital vectors and neglect the mandatory visual lookout required by COLREG Rule 5. ARPA does not detect small wooden boats, floating debris, or vessels not presenting a good radar echo.

-

Misunderstanding of Vectors: A relative vector pointing away from your ship does not guarantee safety. It only shows the current relative motion. If the other vessel is maneuvering, the vector will change. Officers must monitor the trend of the vector, not just its instantaneous direction.

-

Improper Guard Zone Setting: Setting the CPA/TCPA guard alarm limits too tight creates nuisance alarms that officers learn to ignore. Setting them too wide defeats the purpose of an early warning. Limits must be set prudently, considering the navigation area (open ocean vs. narrow channel) and conditions.

Case Study: The Scandinavian Star and the Limits of Technology

A stark historical example, though not solely an ARPA failure, illustrates the consequences of navigational complacency. In 1990, the passenger ship Scandinavian Star collided with a much smaller chemical tanker in the Skagerrak strait. The investigation revealed a series of systemic failures, but key among them was the misuse and misinterpretation of navigational aids.

The OOW on the Scandinavian Star observed a radar target (the tanker) but did not properly utilize ARPA functions to acquire and track it. He made a cursory, incorrect manual plot, severely underestimating the tanker’s speed and concluding there was no risk. Meanwhile, he was distracted by administrative tasks. The ARPA system, had it been used correctly to establish a stable track, would have provided clear and early CPA/TCPA data showing a developing collision situation. This case underscores a vital lesson: Advanced technology is worthless without the disciplined skill and attention of the operator. The most sophisticated ARPA cannot compensate for a lack of fundamental watchkeeping principles, proper procedure, and active situation management.

The Future of Radar Plotting: Next-Generation Systems and Integration

Radar and ARPA technology continues to evolve. Modern Solid-State Radar and Doppler Radar systems offer significantly improved target detection and clarity, especially for small targets in heavy clutter, providing cleaner data for the ARPA tracking engine.

The future lies in deeper sensor fusion. The next generation of integrated bridge systems is moving beyond simply displaying ARPA and AIS targets side-by-side. Advanced systems now perform track fusion, where the radar track from ARPA and the reported position from AIS for the same vessel are combined into a single, more reliable track. This helps resolve conflicts and identify anomalies, like an AIS target with no radar echo (potentially a malfunctioning transponder) or a radar track with no AIS signal (a possible non-equipped vessel).

Furthermore, ARPA overlays on Electronic Chart Display and Information Systems (ECDIS) are becoming standard. This allows the officer to see ARPA tracks and vectors directly on the navigational chart, providing immediate spatial context. Decisions about collision avoidance can be made with full awareness of navigational constraints like traffic separation schemes, shallow water, and designated fairways. This integration represents the ultimate goal: a unified, intelligent situational display that supports holistic decision-making.

FAQ: Radar ARPA in Practice

1. What is the difference between ARPA and AIS for collision avoidance?

ARPA is an independent sensor; it uses your ship’s radar to detect and track objects based on their radar echo. It works with any object that reflects radar waves, but its data is computed and can have errors. AIS is a cooperative transponder system; vessels actively broadcast their GPS-derived position, course, and speed. AIS data is highly accurate for course/speed but requires the other vessel to have a functioning AIS unit. A prudent officer uses both systems to cross-verify information. An ARPA track with no corresponding AIS signal requires extra caution.

2. How long should I wait for an ARPA track to stabilize after acquisition?

You should allow a minimum of 30 seconds to one minute, and observe the target through at least 3-6 radar antenna rotations. The “TRK” or stable track indicator on your display is the best guide. Never make a critical navigational decision based on the initial, unstable data of a newly acquired target.

3. A target’s CPA is 0.5 nautical miles but its TCPA is 45 minutes. Should I be concerned?

You have valuous time, but you must monitor closely. A large TCPA means the situation is developing slowly. However, you should still assess why the CPA is so small. Is the other vessel on a steady course? Is there a chance it might alter course later? Use this time to observe the target’s trend, consider making a small, early course alteration to open the CPA, and plan your actions. Do not ignore a small CPA simply because the TCPA is large.

4. What is the single most important cross-check when using ARPA?

The most critical cross-check is the visual lookout. Whenever possible and safe, try to get a visual bearing of the radar target in question. Match the ship you see out the window with the ARPA target on your screen. This confirms the track’s identity, helps you assess its aspect (which radar does not show clearly), and ensures you are aware of all vessels, not just those showing on radar.

5. My ARPA is showing an alarm for a target with a dangerous CPA, but I can see the ship passing safely. What’s happening?

First, do not ignore the alarm. Acknowledge it, then investigate. The most common causes are: 1) Incorrect ARPA settings, like your own ship’s log input being wrong (speed through water vs. speed over ground), corrupting all calculations; 2) The tracked target has maneuvered, and the ARPA is still processing the change; or 3) A target swap has occurred. Find the correct target, verify your inputs, and monitor the situation until the conflict is clearly resolved.

6. Are manual radar plotting skills still necessary if I have ARPA?

Yes, absolutely. Manual plotting skills are foundational. They are required for coastal navigation and position fixing using radar bearings and ranges. More importantly, the practice of manual plotting teaches you the principles of relative motion that underpin ARPA. If your ARPA fails, you must be able to fall back on manual techniques. These skills are also essential for verifying and understanding what the ARPA is telling you.

7. Who is responsible if a collision occurs due to misinterpreted ARPA data?

Ultimately, the Officer of the Watch (OOW) and the Master are responsible for the safe navigation of the vessel. ARPA is an aid to navigation. The regulations are clear that its use does not relieve the officer of the duty to comply with the COLREGs or maintain a proper lookout. The defense “the ARPA was wrong” is not acceptable if the officer failed to use it correctly or failed to cross-check its information with other available means.

Conclusion: The Prudent Mariner and the Intelligent Aid

The journey from the anxious manual plotter to the modern ARPA-equipped bridge is a story of technological empowerment. ARPA demystifies collision avoidance by providing clear, computed data on target motion, transforming guesswork into informed analysis. Yet, this guide consistently returns to a central, unwavering truth: ARPA is an aid, not an autopilot. Its vectors are predictions, not promises. Its alarms are prompts, not prescriptions.

True mastery of ARPA lies in a balanced approach. It requires the technical skill to operate the system correctly—to acquire, track, and interpret. But more deeply, it demands the professional wisdom to understand its limitations, the disciplined habit to cross-check its outputs, and the seafarer’s vigilance to never let its glowing screen dim your connection to the maritime environment outside the window. Use ARPA as the powerful tool it is to gain early awareness and validate your decisions. But navigate with the enduring principles of watchkeeping, the rules of the road, and your own seasoned judgment. In the balance between digital aid and human responsibility lies the path to truly safe navigation.

References

-

International Maritime Organization (IMO). (2024). SOLAS Chapter V: Safety of Navigation. https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Safety/Pages/SOLAS-Chapters.aspx

-

DNV. (2023). Maritime Guidance: Collision Avoidance. https://www.dnv.com/maritime/

-

International Chamber of Shipping (ICS). (2022). Bridge Procedures Guide. https://www.ics-shipping.org/publication/bridge-procedures-guide-6th-edition-2022/

-

National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB). (2021). Marine Accident Reports. https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Pages/marine.aspx

-

The Royal Institute of Navigation (RIN). (2022). The Use and Misuse of ARPA. https://www.rin.org.uk/publications

-

Marine Insight. (2023). A Practical Guide to Using ARPA Radar. https://www.marineinsight.com/marine-navigation/practical-guide-to-using-arpa-radar/

-

Riviera Maritime Media. (2024). Next-Generation Radar and Sensor Fusion. https://www.rivieramm.com/