Genoa is one of Italy’s most important port systems—yet residents often report congestion, limited green space, weak family amenities, aging housing stock, and restricted access to the sea. This in-depth analysis explains why the port city’s benefits can feel disconnected from everyday urban life and what reforms could restore balance.

Why one of Italy’s most strategic ports fails to translate success into everyday urban livability

Genoa is one of Italy’s most important port systems and a critical logistics gateway for the national economy. Yet many residents describe daily life in terms of congestion, limited green space, weak family amenities, aging housing stock, and restricted access to the sea. This contrast—between strategic importance and lived dissatisfaction—raises a fundamental question: why does a city with such economic weight feel so constrained in everyday terms?

This analysis examines that disconnect. It does not romanticize Genoa’s history or soften resident critiques. Instead, it focuses on the street-level experience: what people navigate daily, what they pay for, what they cannot access, and what repeatedly fails to improve. The objective is not polemic but diagnosis—understanding why these problems persist and what structural reforms would be required for Genoa to function as a modern European port metropolis rather than a city constrained by its own assets.

A core premise runs throughout the analysis:

A globally strategic port does not automatically produce a locally satisfying city.

Port success can coexist with weak urban outcomes when burdens are concentrated locally, while benefits are unevenly distributed, externally captured, or insufficiently converted into visible public goods.

The city that should feel richer than it does

Genoa is often described in superlatives: dramatic geography, extraordinary architecture, a maritime legacy that shaped Europe, and a port complex that functions as a national logistics engine. In theory, these attributes should support a high-performing urban environment—reliable infrastructure, clean and welcoming streets, generous public space, and a waterfront experienced as a civic commons rather than a restricted perimeter.

Yet for many residents, the lived reality diverges sharply from this expectation. Daily life is marked by friction: chronic congestion and parking scarcity; uneven public transport reliability; aging housing stock with slow renewal; visible cleanliness issues involving bins, pavements, and facades; and a shortage of flat, accessible green spaces in the dense neighbourhoods where families actually live.

Underlying these material issues is a deeper symbolic contradiction. Genoa is a city defined by the sea, yet routine, free, and comfortable access to the sea remains surprisingly limited. This dissonance—between identity and experience—shapes much of the city’s frustration.

Geography as a multiplier of failure, not an excuse

Genoa’s geography is not a neutral backdrop; it is an amplifier. The city’s narrow coastal strip, steep hills, and linear development compress urban life into a constrained corridor. This produces several structural conditions:

- limited alternative routes when roads are blocked or congested;

- neighbourhood isolation when transit links, elevators, or funiculars fail;

- scarcity of flat land suitable for parks, sports fields, and civic spaces;

- intense competition for the city–sea interface between port operations, transport infrastructure, and public use.

In cities with space to expand, poor planning can be diluted. In Genoa, margins for error are minimal. Weak planning produces immediate and persistent penalties. Geography becomes a perpetual explanation, while the quality-of-life deficit becomes permanent reality.

The result is a distinctive urban psychology: problems are seen as “understandable” but never resolved. Over time, tolerance erodes.

Infrastructure and mobility: congestion as a daily tax

Port traffic and urban life: a collision of priorities

Genoa’s port handles major freight and passenger flows, requiring continuous operations and high-capacity connectivity. Residents, however, experience the port primarily through its externalities: heavy vehicle movement, noise, emissions, and pressure on already constrained corridors.

The complaint is not simply that traffic is heavy, but that congestion feels structural, as if circulation is designed first for logistics throughput and only secondarily for everyday life. When port trucks share corridors with school runs, buses, deliveries, and emergency services, the city feels perpetually at capacity.

This is a classic port-city dilemma, but one that many global ports have mitigated through dedicated freight corridors, buffer zones, and intermodal systems that reduce truck penetration into residential areas. Genoa has pursued some upgrades, yet residents still feel they are paying the “friction cost” of port success.

Roads: permanent bottlenecks in a narrow corridor

The road network combines narrow historic streets with high-speed infrastructure slicing through dense districts. Outcomes include:

- chronic queues at predictable pinch points;

- minor incidents triggering citywide disruption;

- stressed and aggressive driving behaviour;

- extensive “parking circulation,” adding traffic without movement.

In a structurally narrow city, incremental fixes are insufficient. What residents implicitly demand is functional separation: freight and through-traffic should not compete with residential mobility for the same limited space.

Public transport: geography demands excellence, not adequacy

A dense, steep city should excel at public transport. Yet residents describe uneven service: some corridors work, others feel improvised or fragile. When buses share congested roads, reliability collapses, pushing residents back into private cars and reinforcing a congestion loop. For families and older residents, unreliability has disproportionate costs. Predictability matters more than speed. When transit fails these groups, the city actively undermines social inclusion.

Parking and the erosion of public space

Parking scarcity reshapes behaviour and degrades the public realm:

- sidewalks partially occupied by vehicles;

- blocked corners and reduced visibility;

- double parking slowing buses and emergency services.

In a city already short on flat civic space, the informal appropriation of sidewalks is particularly corrosive. Walkability declines, and with it family friendliness, accessibility for the elderly, and everyday comfort.

Cleanliness, maintenance, and the psychology of neglect

Waste management and street hygiene

Overflowing bins and poorly cleaned streets are not merely operational failures; they shape civic perception. In Genoa’s dense fabric, neglect is highly visible. Residents interpret waste problems as symptoms of broader municipal incapacity. Cleanliness functions as a threshold service. When the public realm looks uncared for, tolerance for other deficits collapses rapidly.

Buildings and facades: beauty trapped in the past

Genoa’s architectural heritage is extraordinary, but everyday perception is shaped by what is most common. Stained facades, deteriorating buildings, and slow maintenance signal stagnation. Residents do not calculate emissions sources; they see outcomes and ask why a port city of national importance cannot manage basic upkeep.

Civic trust and feedback loops

Neglect reduces civic pride, which in turn reduces reporting, care, and compliance. Over time, a credibility gap emerges: citizens assume projects will fail, funds will be misused, and timelines will slip. Governance becomes harder precisely when it needs to be bolder.

Green space: quantity, distribution, and usability

Residents rarely complain about green space in abstract terms. They complain about usable green space:

- flat parks for children and casual sport;

- proximity to dense residential areas;

- safe, everyday accessibility for strollers and elderly users.

In Genoa, much “green” is steep hillside terrain. Beautiful, but functionally limited. A park that requires a strenuous climb does not replace neighbourhood-level green.

Urban enclosure and psychological fatigue

Tall buildings and narrow streets create an “urban canyon” effect. Without relief through squares, parks, or open vistas, density becomes oppressive. Dense living works when balanced by generous public space; without it, fatigue accumulates.

Green inequality and demographic sorting

Uneven distribution of green space drives social sorting. Families with means relocate; dense working districts age. Over time, the city becomes older not only demographically, but functionally.

Demographics: Why Genoa Is Graying? A city ageing faster than it renews

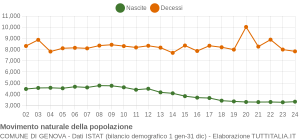

While the Italians may have mastered the arts of pasta, wine and gelato, they should have been spending less time in the kitchen and more in…another room. That’s right, we’re looking at the demographic problems facing Italy, and Genoa will be our example. The population of Genoa in 1972 was 950,000. Today, it is under 680,000. The scary part is that Genoa isn’t an isolated instance. Italy’s birth rate has been below replacement level for over 75 years, leading to an aging population and a shrinking tax base. The scarier part is that Italy is just one example of a country facing demographic collapse, as places like Germany, Romania, and Spain are all in the same boat.

Unfortunately, there’s really no practical solutions for these countries to remedy this issue. Sustaining their economies and state functions without a younger generation won’t be easy, but at least we’ll see how nations can adapt to these demographic challenges.

Genoa’s aging profile is visible in services, retail mix, and daily rhythms. Pharmacies replace playgrounds; continuity replaces experimentation. Resources flow toward immediate elderly needs, while long-term investments for families and youth lag.

The perception that pets outnumber children is not trivial. It signals an environment where raising a child is structurally harder than raising a pet—due to parks, housing, mobility, and services. Youth outmigration compounds the problem. As young adults leave, the city loses its future tax base, cultural dynamism, and demographic renewal, reinforcing a conservative investment cycle.

The port–city value exchange: extraction without visibility

Residents often perceive the port as extractive: it occupies scarce waterfront land, generates traffic and pollution, and imposes costs, while visible improvements in daily life remain limited. This perception is reinforced by:

- value leakage to external firms and headquarters;

- labor mismatch limiting local access to port jobs;

- fiscal asymmetry restricting municipal capture;

- externalized costs borne locally.

Residents evaluate outcomes, not aggregate GDP. When benefits are invisible, resentment is rational.

Congestion, pollution, and environmental injustice

Freight traffic intensifies congestion and exposure to NO₂ and PM₂.₅. Even compliant emissions feel unjust when risks are local and benefits global.

Cruise tourism: volume without relief

High-volume, low-spend tourism crowds streets and buses without proportional reinvestment. The city absorbs peaks; benefits diffuse elsewhere.

Housing pressure and short-term rentals

Tourism demand fuels Airbnb expansion, reducing long-term housing supply, raising rents, and accelerating displacement—especially in historic and port-adjacent districts.

The missing tool: a visible port dividend

Cities that succeed institutionalize port-to-city benefit mechanisms: air-quality funds, mobility upgrades, noise mitigation, housing support. Where these are absent, the port becomes an enclave.

Housing and urban form: stagnation and mismatch

Residents’ claim that there is “no new housing” reflects not a literal absence of construction, but a perception of stagnation in renewal and a mismatch between supply and contemporary needs. What feels scarce is not housing in general, but functional, affordable, and family-suitable dwellings.

Much of Genoa’s housing stock is old and physically constrained. Many buildings lack elevators, have inefficient layouts, and poor insulation. For elderly residents, stairs become daily barriers that trap people in their homes or force relocation. For families, older apartments often fail to provide flexible space or reasonable energy performance, increasing costs and discomfort. When renewal is slow, the city appears locked into a past housing model that no longer fits its demographic reality.

Affordability compounds this mismatch. Even when units exist, renovation costs and market pressures—especially in central and coastal areas—make modern housing inaccessible to young households. The result is a paradox: visible vacancies or underused buildings alongside a shortage of attractive long-term options for families. Peri-urban development offers little relief. Instead of coherent, green, transit-connected neighbourhoods, expansion has often been fragmented and car-dependent. These areas deliver neither urban convenience nor suburban comfort, forcing long commutes and weakening social life.

Waterfront redevelopment adds further tension. When investment flows into prestige projects or luxury housing while neighbourhood-level deficits—such as lifts, insulation, and playgrounds—remain unresolved, residents read renewal as symbolic rather than structural. The city appears capable of showcase projects but unable to modernize everyday living conditions. Housing stagnation therefore signals more than technical failure. It communicates whether Genoa is investing in its residents’ future or merely curating an image for outsiders. Without socially balanced renewal, the city will struggle to retain families, adapt to aging, or stabilize demographically.

Retail, shopping malls, convenience, and everyday friction

Complaints about the lack of major shopping centres point and shopping malls to a deeper issue: everyday logistics. In modern cities, retail hubs function as family infrastructure, concentrating services—food, pharmacies, cafés, toilets, parking—into predictable, accessible environments. When such facilities are perceived as insufficient or poorly integrated, residents are expressing frustration about routine tasks becoming stressful. The issue is not consumption but time and effort, especially for families, elderly residents, and people with limited mobility.

Genoa’s commercial landscape is strong in neighbourhood retail but highly fragmented. Basic errands often require navigating congestion, searching for parking, climbing slopes, and moving between dispersed shops. Combined with narrow sidewalks and poor pedestrian comfort, what could be charming becomes exhausting.

Poor walkability intensifies this friction. Obstructed sidewalks, unsafe crossings, and dirty streets turn walking into an obstacle course, particularly for strollers and older residents. Retail accessibility is inseparable from street quality. The lack of integrated commercial hubs also weakens social cohesion. In many cities, shopping centres and mixed-use districts function as informal civic spaces for teenagers and families. Without such nodes, Genoa risks becoming a mosaic of disconnected commercial pockets linked by stressful corridors rather than a coherent urban system.

Over time, this daily friction shapes perception more than large projects. Residents judge the city by how easy it is to buy food, take children to activities, or meet friends without planning around congestion. When routine life feels hard, the city feels unsupportive, regardless of its heritage or architecture.

The waterfront: Genoa’s deepest emotional grievance

In a city with limited parks, steep terrain, and dense districts, access to the sea is not a luxury but a necessity—one of the few everyday outlets that can relieve congestion, heat, and spatial pressure. The waterfront should function as a civic living room: a place for walking, children’s play, and low-cost leisure.

Instead, much of Genoa’s coastline remains fragmented, restricted, or pay-gated. The practical experience is that the sea is central to the city’s identity but marginal in daily life. This contradiction produces not only inconvenience but a sense of dispossession: a maritime city that cannot be lived as maritime.

Physical barriers—port zones, transport corridors, and security perimeters—create a broken edge: discontinuous promenades, limited access points, and visual but not physical proximity to the water. Where large parts of the usable coast are organized around pay-to-enter facilities, residents internalize the idea that the sea is a commodity rather than a common good. This is about dignity and equality as much as affordability.

The grievance is sharper in Genoa because alternatives are few. Dense neighbourhoods lack flat parks, and hills limit the usability of existing green areas. When both parks and sea access are scarce, dense living loses its psychological “pressure valves.” Each accessible stretch of coast therefore carries disproportionate civic value.

Waterfront redevelopment offers an opportunity but also a credibility risk. Residents will judge success by simple criteria: Can they reach the water easily and freely? Can children play there? Are there benches, shade, toilets, and safe paths? If projects deliver prestige architecture or luxury housing without improving daily access, resentment deepens: the city can build symbols but not basics.

The governance challenge is to treat the waterfront as public infrastructure—with continuous pedestrian routes, guaranteed access corridors, and enforceable limits on concessions—rather than as a patchwork of restricted zones.

Child-friendliness: when small deficits become decisive

Child-friendliness is not a single facility but a system of small reliabilities: clear sidewalks, nearby parks, predictable transport, suitable housing, indoor spaces for winter, and basic cleanliness. Parents measure a city by daily feasibility, not slogans.

In Genoa, many families experience a city that requires adult endurance rather than family ease. Individually, each deficit seems tolerable; together, they become decisive. Topography turns short distances into effort, congestion makes time unpredictable, parking stress reduces spontaneity, flat green space is scarce, and sea access cannot compensate.

This matters because families choose cities based on everyday friction. When raising children feels structurally harder in one place than another, outmigration is rational, not cultural. Tourism and retirement cannot substitute for families. Families generate long-term attachment, demand for public services, stable local economies, and future workers. A city that implicitly optimizes for visitors and retirees while making family life difficult risks demographic hollowing. Child-friendliness is therefore not sentimental policy; it is competitiveness policy.

A city prioritizing senior services (healthcare, pensions) over youth infrastructure (parks, schools, childcare) risks long-term stagnation. This isn’t about choosing one group over the other, but about correcting a strategic imbalance. Focusing only on an aging population’s immediate needs, while neglecting investments for young families, can trigger a “youth drain.” This leads to future labor shortages and reduced vitality. The lack of shared spaces also deepens social divides between generations.

The solution is integrated, intergenerational planning. A resilient city provides quality eldercare and invests in:

- Family Infrastructure: Green spaces, affordable childcare, and well-funded schools.

- Shared Public Life: Parks, libraries, and cultural events designed for all ages.

True prosperity requires honouring the present population while investing in the future, building a community where all generations belong.

A reinforcing system of decline

Genoa’s problems operate as a self-reinforcing loop, not as isolated failures. Residents sense a pattern rather than a list of defects.

A simplified cycle is:

-

Congestion and freight pressure reduce mobility reliability.

-

Unreliable transit pushes residents toward cars, worsening congestion.

-

Parking stress and traffic degrade walkability and public space.

-

Limited parks and restricted waterfront access remove daily relief from dense living.

-

Stress and inconvenience accelerate youth and family outmigration.

-

Outmigration intensifies aging, shifting priorities toward short-term elderly needs.

-

Investment in child-oriented amenities and renewal weakens.

-

Housing and public space stagnate; civic trust declines.

-

Low trust makes large reforms politically harder.

-

The cycle restarts.

This is why isolated projects rarely shift perception. A new promenade or park does little if transit remains unreliable and streets remain congested and dirty. Improvements are read as cosmetic rather than structural.

The core diagnosis is a conversion failure: Genoa produces strategic value through its port and connectivity but does not consistently convert that value into the everyday fundamentals residents measure—clean streets, predictable mobility, accessible green space, affordable family housing, and open sea access. Until that conversion becomes visible at neighbourhood level, dissatisfaction will persist regardless of macroeconomic performance.

What would have to change: a livability-first reform agenda

Reform must be visible and street-level:

-

Mobility: separate freight and residential flows; guarantee transit reliability.

-

Public realm: cleanliness and maintenance as core infrastructure.

-

Family urbanism: parks, play, youth spaces distributed by neighbourhood.

-

Waterfront access: continuous, affordable public commons.

-

Housing renewal: modern, family-suitable stock and accessible retrofits.

-

Port governance: a transparent, measurable port dividend.

Conclusion: Genoa’s problem is not the port—it is the missing balance

Genoa can remain a national logistics engine and become a livable city—but only if it converts strategic success into everyday benefit. Heritage and tourism can sustain a city temporarily. Livability fundamentals sustain it generationally.

The port is not the enemy. Invisibility of benefit is.

–

References

-

SRM / OsserMare, Report OsserMare-SRM 2025 (PDF).

-

ANSA Liguria (13 Jan 2026), “Porto Genova, nel 2025 quasi 4 milioni di passeggeri.”

-

Genova24 (13 Jan 2026), “Genova, porto passeggeri da record: il bilancio del 2025 e le sfide del 2026.”

-

ISTAT, “Ambiente urbano – Anno 2022” (release page and datasets hub).

-

ISTAT, Tavole verde urbano 2022 (XLSX dataset).

-

ISTAT, “Quantificazione delle aree verdi” (experimental statistics page).

-

Reuters (20 May 2024), “More than a third of Italian teens want to emigrate, survey finds.”

-

Reuters (20 Jun 2025), “Italy’s immigration and emigration both soaring, stats agency says.”

-

AMIU Genova (29 Sept 2025), “Problematiche di conferimento della frazione indifferenziata” (press release PDF).

-

Genova24 (29 Sept 2025), “Rifiuti, smaltimento a rischio blocco…”

-

Waterfront di Levante (official project site).

-

Comune di Genova (17 Jul 2020), “Waterfront di Levante: il parco urbano…” (municipal update).

-

Italia.it, “Waterfront di Levante” (project overview).

-

EU News (9 Aug 2024), “The last chapter in the Bolkestein saga in Italy…” (beach concessions).

-

Euronews (23 Aug 2024), “Beach wars: are EU and Italy close to resolving beach concession feud?”

-

SSRN Working Paper (11 Jun 2025), “The battle over Italian beaches: EU-induced liberalization…”

-

Italian Journal of Public Law (2022), Angela Cossiri, “Italian beach concessions…” (PDF).

-

Financial Times (2025), “The fight for Italian beaches heats up.”