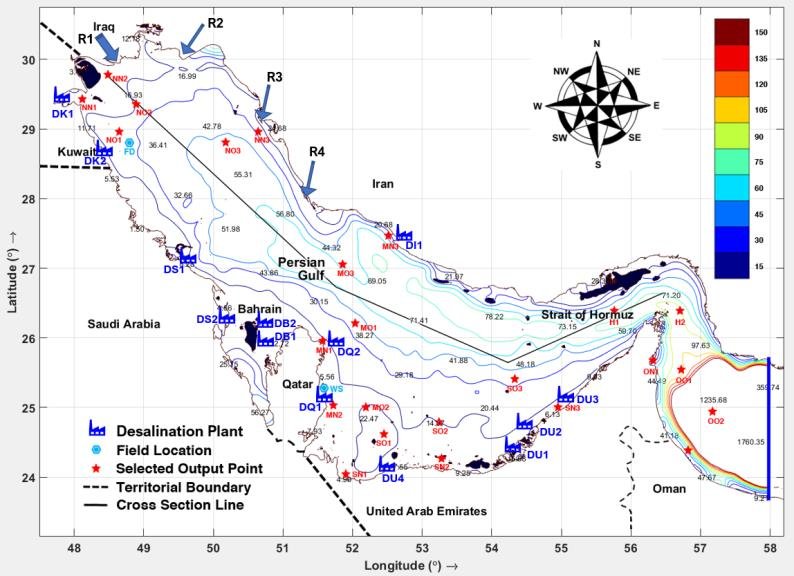

Location map of desalination plants in the Persian Gulf with the Gulf bathymetry.

The Arab states of the Persian Gulf—Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, and Oman—present a paradox of monumental scale. They are home to some of the world’s most audacious urban landscapes, command immense geopolitical influence through hydrocarbon wealth, and project an image of hyper-modernity and enduring stability. Yet, beneath this glittering veneer lies a profound and multi-layered fragility, a societal and infrastructural house of cards perilously dependent on a single, vulnerable technological marvel: the conversion of seawater into drinking water. An event in the Persian Gulf that interrupts or destroys their desalination capacity—be it a massive radioactive pollution event, a war targeting critical infrastructure, or a catastrophic environmental disaster—would not merely be a humanitarian crisis. It would be an existential shockwave, exposing the fundamental vulnerabilities of these states and threatening to unravel the very fabric of their societies. These are not merely brittle states; they are potentially breakable societies, whose stability is contingent on the uninterrupted hum of desalination plants.

The Lifeblood of the Desert: Absolute Dependence on Desalination

To understand the fragility, one must first grasp the absolute nature of the Gulf’s water crisis. The region is one of the most water-scarce on earth. Natural renewable water resources are negligible; groundwater is fossil, non-replenishable, and has been massively over-drawn for decades, leading to severe depletion and salinization. Rainfall is minimal and erratic. There are no permanent rivers.

In this context, desalination is not a convenience or a supplement; it is the singular artery of survival. Over 90% of the drinking water in Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE comes from desalination. The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states account for approximately 40% of global desalinated water output, operating over 400 plants, most of which are coastal and draw directly from the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman. This water supplies not only households but is the lifeblood of industry, commerce, tourism, and crucially, the high-value, water-intensive agriculture that exists only thanks to state subsidy and strategic desire for partial food self-sufficiency.

The infrastructure is colossal but intensely concentrated. Plants like Saudi Arabia’s Ras Al-Khair (the world’s largest), the UAE’s Jebel Ali, and Qatar’s Ras Abu Fontas are not just utilities; they are strategic national assets of higher immediate importance than many oil installations. Their operation is a daily, non-negotiable imperative. The dependency is total, creating a critical single point of failure for entire nations.

–

The Nature of the Catastrophic Interruption: Scenarios of Collapse

A disruption to this system would not be a mere shortage; it would be a systemic collapse. The triggering events fall into two broad, potentially overlapping categories: environmental and military.

1. Environmental Catastrophe: The “Dead Gulf” Scenario

Imagine a catastrophic event that renders the seawater feedstock of the desalination plants unusable. The most potent threat is massive radioactive pollution. This could stem from:

-

A military strike on Iran’s Bushehr nuclear power plant, or a catastrophic meltdown and breach of containment, spewing cesium-137, strontium-90, and other isotopes into the Gulf’s shallow, enclosed basin. The prevailing northwest-southeast currents would spread contamination down the coastline of all the GCC states.

-

The use of a tactical nuclear weapon or a “dirty bomb” in or near the Strait of Hormuz, intentionally designed to pollute the choke point.

Radioactive seawater is beyond the design parameters of Reverse Osmosis (RO) or Multi-Stage Flash (MSF) desalination plants. Intakes would suck in contaminated water. The membranes of RO plants, the heart of the process, would be fouled and become radioactive waste themselves. The entire plant—pipes, pumps, filtration systems—would become contaminated. Even if plants could be shut down in time, the question becomes: with what water do you flush and clean them? Where do you dispose of the radioactive brine concentrate, already a environmental challenge? The Gulf’s slow flushing rate (a full renewal takes 3-5 years) means the contamination would persist for years, making coastal desalination impossible. Alternative intakes from the Gulf of Oman or the Red Sea (for Saudi Arabia) would require years and billions to build new pipeline networks.

Other environmental disasters could have a similar effect. A monsturous, sustained Harmful Algal Bloom (HAB or “red tide”), exacerbated by warming waters and agricultural runoff, could clog intakes and produce toxins that are difficult and slow to filter. A simultaneous, multi-point sabotage of oil terminals and tankers could create a sludge blanket of crude oil that would coat intakes and render separation economically and technically unviable for months.

2. Military Targeting: The “Crippling Blow” Scenario

In a regional conflict, desalination plants are not merely collateral damage risks; they are prime strategic targets. An adversary seeking to impose unbearable costs without necessarily invading territory would logically target these facilities. A coordinated missile and drone strike campaign—employing precision munitions, cheap drones, or even cyber-attacks on SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) systems—could disable multiple key plants simultaneously. The attacks need not be nuclear; conventional explosives on intake manifolds, high-pressure pumps, electrical substations, or control rooms could cause outages lasting months due to the need for specialized, often imported, replacement parts.

The symbolism is as potent as the physical effect. Striking the water supply is an attack on the state’s most fundamental covenant with its population: the provision of basic survival. It bypasses armies and directly targets societal resilience.

–

The Layers of Fragility Exposed

A water stoppage would act like a shockwave, radiating through every layer of Gulf society and exposing its interconnected vulnerabilities.

Layer 1: The Physical and Economic Collapse

-

Immediate Human Crisis: Within 72 hours, tap water pressure would drop. Within a week, bottled water would vanish from shelves, leading to panic buying, hoarding, and black markets. The World Health Organization’s minimum emergency standard is 15 liters per person per day for drinking, cooking, and hygiene. Gulf citizens and expatriates, accustomed to some of the highest per capita consumption rates globally (often over 300 liters/day in the UAE), would face an instant, draconian reduction. Heat stress, dehydration, and waterborne diseases from using contaminated backup supplies would surge, especially among the vulnerable: the elderly, children, and outdoor laborers.

-

Hyper-Inflation of Water: Water would become the most valuable commodity, priced in gold. The social contract, built on abundant provision, would shatter.

-

Economic Paralysis: Without process water, the oil and gas industry—the source of all wealth—would grind to a halt. Refineries, petrochemical plants, and cooling systems require vast amounts of water. Finance, tourism, and construction would cease. The global economy would reel from the interruption of 20% of the world’s oil supply, but the local economy would be in freefall.

Layer 2: The Demographic Time Bomb

The Gulf’s demographic structure is a core vulnerability. In most GCC states, expatriates constitute 70-90% of the population. Their presence is purely transactional: they provide labor and expertise in exchange for salary and a safe, modern living environment. This population is segmented and hierarchical, from Western executives to South Asian construction workers.

A water catastrophe would trigger a mass exodus of apocalyptic proportions. Those with means and foreign passports—Western professionals, Arab elites from other regions—would flee immediately via air or land. The real crisis would be among the millions of low-income expatriates from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, the Philippines, and Egypt. With no savings, no viable way home (airports would be chaos, governments might not have the funds or will to repatriate them), and facing thirst, they would become a desperate, displaced population. Labor camps, often on the urban periphery, would transform into zones of humanitarian disaster and potential unrest. The state’s ability to maintain control and provide for this non-citizen majority would be instantly overwhelmed. The resulting chaos would make the 1990-91 Gulf War exodus look orderly.

Layer 3: The Political and Social Fracturing

The Gulf states are neo-patrimonial monarchies where legitimacy is derived from three pillars: religious authority (custodianship of holy sites in Saudi Arabia, or association with Islamic values), historical tribal legitimacy, and, most critically, the distribution of hydrocarbon wealth into a comprehensive welfare state—tax-free incomes, lavish subsidies, government jobs, free utilities (including water), and world-class services.

A water collapse would obliterate this distributive pillar. The state would be seen as failing in its most basic duty. The implicit social contract—political acquiescence in exchange for wealth and security—would be null and void.

-

Citizen vs. State: Citizens, while a minority, are not a monolith. Long-standing tensions between ruling families and other elite tribes, between Sunni and Shia populations (particularly in Bahrain, Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province, and Kuwait), and between urban cosmopolitan and more conservative rural/nomadic communities could flare. Scapegoating and accusations of mismanagement would be rampant.

-

Citizen vs. Expatriate: As resources vanish, xenophobic and nationalist sentiment would explode. The narrative of the “guest worker” would collapse, replaced by a zero-sum competition for survival. Citizens might demand prioritization, leading to state-sanctioned discrimination or vigilante violence against expatriate communities. The Kohlhase-Haddad scenario of 1990s Kuwait, where Palestinians were collectively punished for the PLO’s support of Saddam, would be replayed on a horrific, regional scale.

-

Intra-Expatriate Violence: Competition between different expatriate nationalities and socioeconomic groups for dwindling supplies could lead to riots and inter-communal violence within labor camps and districts.

Layer 4: The Geopolitical Domino Effect

The crisis would not be contained. The region would become a vortex of great power competition and regional conflict.

-

Mass Migration Crisis: Millions of refugees would attempt to flee overland into Jordan, Iraq, and Turkey, or by sea across the Gulf to Iran and Pakistan, creating an unprecedented regional humanitarian and security crisis.

-

Military Intervention: The United States, with its Fifth Fleet headquartered in Bahrain and critical bases in Qatar and the UAE, would face an impossible choice. Its forces would be drawn into direct humanitarian and security operations, potentially clashing with desperate populations. China, with its deep economic ties and massive expatriate workforce, might also consider intervention. The risk of direct confrontation between powers in the chaos would be high.

-

Regional Aggression: A weakened Saudi Arabia or UAE might be seen as an opportunity by regional adversaries or non-state actors. The entire balance of power in the Middle East would be upended.

-

Global Economic Shock: The permanent loss of Gulf oil and gas exports (even for 6-12 months) would trigger a global depression. The financial collapse of sovereign wealth funds (like the UAE’s ADIA or Saudi Arabia’s PIF), as they liquidate assets to fund crisis response, would destabilize global markets.

–

Resilience and Response: The Limits of Preparation

Gulf states are not blind to this vulnerability. They have undertaken significant efforts to build resilience:

-

Strategic Water Reserves: The UAE and Saudi Arabia have built vast underground aquifers in desert reservoirs, holding up to 90 days of supply. Kuwait and Qatar have similar, smaller-scale storage.

-

Diversification of Technology: Investment in more efficient RO plants, research into renewable-energy desalination, and even cloud seeding.

-

Infrastructure Interconnection: The GCC Water Grid, a long-discussed project to connect the six states’ water networks, aims to allow sharing in a crisis. Progress has been slow and politically fraught.

-

Food Security Strategies: Moving some agriculture abroad (e.g., Saudi leases in Sudan and Ethiopia), and investing in controlled-environment hydroponics.

However, these measures are woefully inadequate for a total, prolonged cessation.

-

90 days of water is not enough. It is a buffer for a technical fault or a short-term disruption. It is not a solution for a Gulf-wide environmental catastrophe that could last years. The reserves would be consumed long before any meaningful alternative infrastructure could be built.

-

The Grid assumes someone has water to share. In a Gulf-wide event, all states are crippled simultaneously. There is no “outside” within the region to provide help.

-

Logistics would collapse. Distributing stored water without functioning utilities, amid societal breakdown and without truck drivers (who are mostly expatriates who may have fled or be in crisis themselves), is a near-impossible task.

Conclusion: The Ephemeral Oasis

The Arab Gulf states represent one of humanity’s most ambitious attempts to defy geography through technology and capital. They have built thriving societies in one of the planet’s most inhospitable climates. But this achievement has created a profound, systemic vulnerability. Their societies are engineered, not organic; they are sustained by a continuous, energy-intensive process that is breathtakingly centralized and exposed.

A catastrophic interruption of desalination would be more than an infrastructure failure. It would be a cascading failure of the entire Gulf model. It would expose the demographic imbalance, stress the political legitimacy to its breaking point, unravel the social fabric, and trigger regional and global crises of the first order. The very technologies and wealth that created these modern marvels have also created a unique and acute fragility.

They are not fragile because they are weak; they are fragile because their complexity and interdependence are so extreme, and their margin for error is so slim. The Persian Gulf is their lifeline and their potential Achilles’ heel. An event that poisons or denies them its waters would not just cause hardship; it would demonstrate, in the most brutal way possible, that the glittering cities of the Gulf are, in the final analysis, precarious oases—extraordinarily sophisticated, yet ultimately breakable societies living on borrowed time and desalinated water. Their continued existence depends on the relentless, uninterrupted operation of machines along their shores, a fact that makes their future uniquely sensitive to the volatile politics and environmental health of the Persian Gulf.