A clear, practical guide to electronic position fixing and navigation systems on ships, covering GPS, ECDIS, INS, AIS, regulations, challenges, and future trends.

For centuries, mariners relied on stars, compasses, and coastal landmarks to know where they were at sea. Today, a modern ship’s bridge resembles a digital control room, where satellites, sensors, and computers continuously calculate the vessel’s position with extraordinary precision. These electronic systems of position fixing and navigation are no longer optional conveniences; they are safety-critical systems that underpin collision avoidance, voyage efficiency, regulatory compliance, and environmental protection.

From large container ships crossing oceans to coastal ferries navigating congested waters, electronic navigation systems provide the situational awareness that allows crews to operate safely in an increasingly complex maritime environment. Understanding how these systems work, how they complement each other, and where their limitations lie is essential knowledge for deck officers, maritime students, ship managers, and regulators alike.

Electronic position fixing and navigation systems form the backbone of modern maritime operations. Accurate positioning supports safe route planning, precise track-keeping, efficient fuel use, and compliance with international conventions. In congested sea lanes, ports, and narrow channels, these systems reduce human workload and help prevent groundings and collisions. At the same time, over-reliance without proper understanding can introduce new risks, making professional competence and system awareness critical.

Core Concepts of Electronic Position Fixing

Electronic position fixing refers to determining a ship’s geographical position using electronic signals rather than visual bearings or celestial observations. In practice, modern ships rely on multiple, independent systems to ensure redundancy and resilience.

Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS)

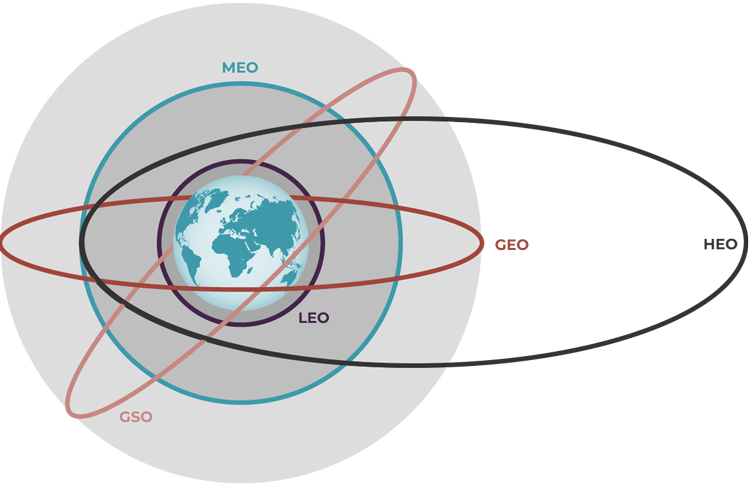

At the heart of most electronic navigation is satellite positioning. The most widely known system is Global Positioning System (GPS), operated by the United States. GPS uses a constellation of satellites that transmit time-stamped signals. A receiver onboard the ship calculates its position by measuring the time delay from multiple satellites, producing latitude, longitude, and often altitude.

Other satellite systems operate on similar principles. GLONASS, Galileo, and BeiDou provide global or regional coverage. Modern marine receivers often use multiple constellations simultaneously, improving accuracy and availability.

Satellite positioning offers meter-level accuracy under normal conditions. However, it depends on external signals that can be degraded by atmospheric effects, antenna problems, or intentional interference such as jamming and spoofing. This vulnerability explains why regulations and best practice insist on redundant position fixing methods.

Differential GNSS and Augmentation Systems

To improve accuracy and integrity, satellite positioning can be enhanced by correction signals. Differential GNSS (DGNSS) uses reference stations at known locations to calculate errors and broadcast corrections to ships in the area. Regional augmentation systems further refine positioning and provide integrity monitoring, alerting users when the signal should not be trusted.

These enhancements are particularly important for coastal navigation, pilotage, and port approaches, where small position errors can have serious consequences.

Electronic Chart Display and Information System (ECDIS)

The most visible expression of electronic navigation on today’s bridge is the Electronic Chart Display and Information System, universally known as ECDIS. ECDIS integrates electronic navigational charts with real-time position data, radar overlays, AIS targets, and other sensor inputs.

How ECDIS Works

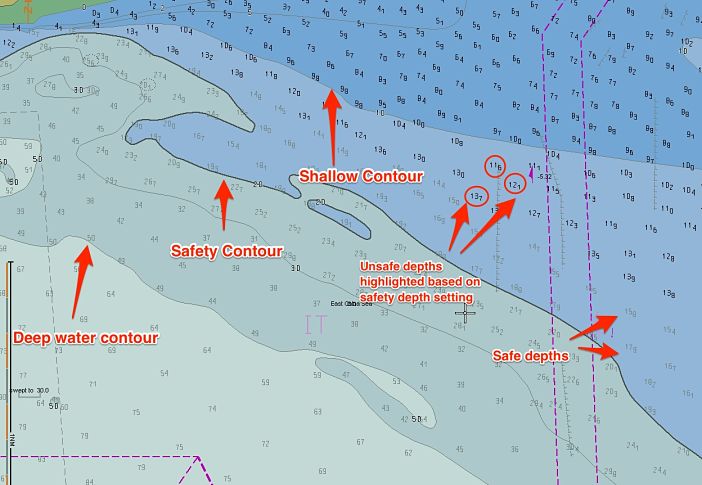

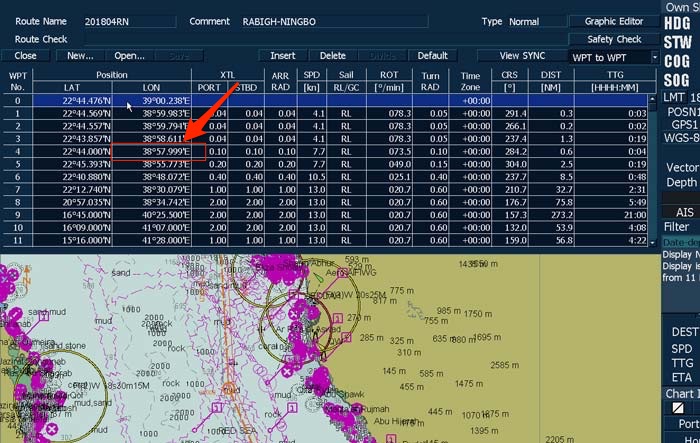

ECDIS replaces paper charts with official Electronic Navigational Charts (ENCs) issued by hydrographic offices. The system continuously plots the ship’s position on the chart, displays planned routes, and monitors the vessel’s progress against safety parameters such as under-keel clearance, safety depth, and cross-track limits.

Instead of manually transferring positions to a paper chart, officers can immediately see whether the ship is deviating from its intended track or approaching danger. Audible and visual alarms alert the bridge team to potential hazards, helping to prevent grounding.

Regulatory Importance of ECDIS

The mandatory carriage of ECDIS on most SOLAS ships reflects its safety value. Requirements are set by the International Maritime Organization under the SOLAS Convention, with detailed performance standards and training obligations. Officers in charge of a navigational watch must receive approved ECDIS training, recognizing that technology alone does not guarantee safety.

Radar and ARPA as Position Fixing Aids

Radar remains one of the most robust navigation tools at sea. Unlike satellite systems, radar is an independent sensor that detects physical objects by transmitting radio waves and measuring their reflections.

Radar Fixing and Parallel Indexing

By identifying fixed objects such as coastlines, buoys, or prominent structures, radar can be used to fix a ship’s position. Techniques like range and bearing measurements or parallel indexing allow navigators to monitor the vessel’s track relative to known features, providing a valuable cross-check against satellite-based positions.

Automatic Radar Plotting Aid (ARPA)

Modern radars are equipped with Automatic Radar Plotting Aid (ARPA) functions that automatically track targets, calculate their course and speed, and assess collision risk. While ARPA is primarily a collision-avoidance tool, its integration with chart systems contributes to overall navigational awareness.

Integrated Navigation Systems (INS)

As navigation technology evolved, individual systems became increasingly interconnected. An Integrated Navigation System (INS) combines GNSS, gyrocompass, radar, ECDIS, speed log, echo sounder, and sometimes autopilot into a unified interface.

The advantage of integration lies in consistency and reduced workload. Data entered once, such as a voyage plan, can be shared across multiple systems. At the same time, integration increases complexity, making system understanding and redundancy management even more important.

Automatic Identification System (AIS)

The Automatic Identification System (AIS) broadcasts a ship’s identity, position, course, and speed to other vessels and shore stations. While AIS is not a primary position-fixing system, it plays a significant role in situational awareness.

When overlaid on ECDIS or radar, AIS targets help bridge teams quickly identify nearby traffic. However, AIS data relies on the transmitting ship’s own sensors and can be inaccurate or deliberately falsified, reinforcing the principle that no single system should be trusted blindly.

Gyrocompass, Speed Logs, and Echo Sounders

Electronic navigation depends not only on position but also on accurate heading, speed, and depth information.

The gyrocompass provides true heading, essential for chart alignment and radar operation. Speed logs measure the ship’s speed through the water or over the ground, influencing position prediction and voyage efficiency. Echo sounders provide depth information, offering an additional check against charted depths and helping detect unexpected shoaling.

Together, these sensors create a coherent picture of the ship’s movement and environment.

–

Key Developments and Technological Evolution

From Stand-Alone Systems to Digital Bridges

Early electronic navigation systems operated independently. Today’s bridges reflect a shift toward digital integration, automation, and decision support. High-resolution displays, touch interfaces, and sensor fusion allow navigators to access more information than ever before.

Cybersecurity and Signal Resilience

As navigation systems became digital and networked, cybersecurity emerged as a critical concern. Reports of GNSS jamming and spoofing have highlighted vulnerabilities. Industry guidance from organizations such as International Association of Classification Societies emphasizes resilience, redundancy, and crew awareness to mitigate these risks.

Challenges and Practical Solutions

Despite their benefits, electronic navigation systems introduce new challenges. One of the most common issues is over-reliance on automation. When officers trust the display without questioning the underlying data, errors can go unnoticed. Poorly configured safety settings on ECDIS, such as incorrect safety depth values, have been identified as contributing factors in several grounding accidents investigated by authorities like the Marine Accident Investigation Branch.

Training and bridge procedures provide practical solutions. Regular cross-checking between independent systems, maintaining paper chart familiarity where required, and conducting position verification using radar or visual means help maintain situational awareness. Clear bridge team communication ensures that technology supports, rather than replaces, professional judgment.

Case Studies and Real-World Applications

Accident investigations repeatedly demonstrate both the strengths and weaknesses of electronic navigation. In several well-documented groundings, ships were fitted with compliant ECDIS systems, yet improper route planning or alarm management led to loss of situational awareness. Conversely, there are countless unreported cases where timely ECDIS alarms or radar cross-checks prevented incidents in poor visibility or congested waters.

On the commercial side, optimized electronic navigation contributes to fuel efficiency. Accurate track-keeping and route monitoring reduce unnecessary deviations, supporting emission-reduction goals promoted by organizations such as International Chamber of Shipping and UNCTAD.

Future Outlook and Maritime Trends

The future of electronic position fixing and navigation is shaped by automation, connectivity, and resilience. Developments in e-Navigation, promoted by the IMO, aim to harmonize digital information exchange between ships and shore. Enhanced GNSS resilience, alternative positioning methods such as terrestrial radio navigation, and improved decision-support tools will likely feature prominently.

Autonomous and remotely operated vessels place even greater emphasis on reliable electronic navigation. In such contexts, system integrity, redundancy, and cybersecurity become not just safety issues but fundamental enablers of new operational models.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the main electronic system used for position fixing on ships?

Most ships rely on GNSS, particularly GPS, often combined with other satellite constellations for redundancy.

Is ECDIS mandatory on all ships?

ECDIS is mandatory on most SOLAS-class vessels, depending on ship type and size, under IMO regulations.

Why are multiple navigation systems required?

Redundancy ensures safety. If one system fails or provides incorrect data, others can verify or replace it.

Can electronic navigation systems completely replace paper charts?

Where ECDIS is approved and correctly used, it can replace paper charts, but crews must still understand traditional navigation principles.

What are the main risks of electronic navigation?

Over-reliance, poor training, incorrect settings, and signal interference are among the most significant risks.

How does AIS support navigation?

AIS enhances situational awareness by sharing vessel identity and movement data, but it should never be the sole source of information.

Conclusion

Electronic systems of position fixing and navigation have transformed maritime operations, delivering unprecedented accuracy, efficiency, and situational awareness. Systems such as GNSS, ECDIS, radar, and integrated bridges work together to support safe navigation in an increasingly demanding environment. Yet technology alone is not enough. Competent training, critical thinking, and adherence to best practice ensure that these systems remain powerful allies rather than hidden hazards. For maritime professionals and students, mastering electronic navigation is not just about operating equipment; it is about understanding its strengths, limitations, and role within the broader safety culture of shipping.

References

International Maritime Organization. SOLAS Convention and ECDIS Performance Standards.

International Chamber of Shipping. Bridge Procedures Guide.

International Association of Classification Societies. Guidance on Cyber Security and Navigation Systems.

Marine Accident Investigation Branch. Accident Investigation Reports on ECDIS-Related Incidents.

UNCTAD. Review of Maritime Transport.

Bowditch, N. The American Practical Navigator.