How navigational equipment data is integrated on ships to maintain a safe navigational watch, meeting COLREG, STCW, and modern bridge safety standards.

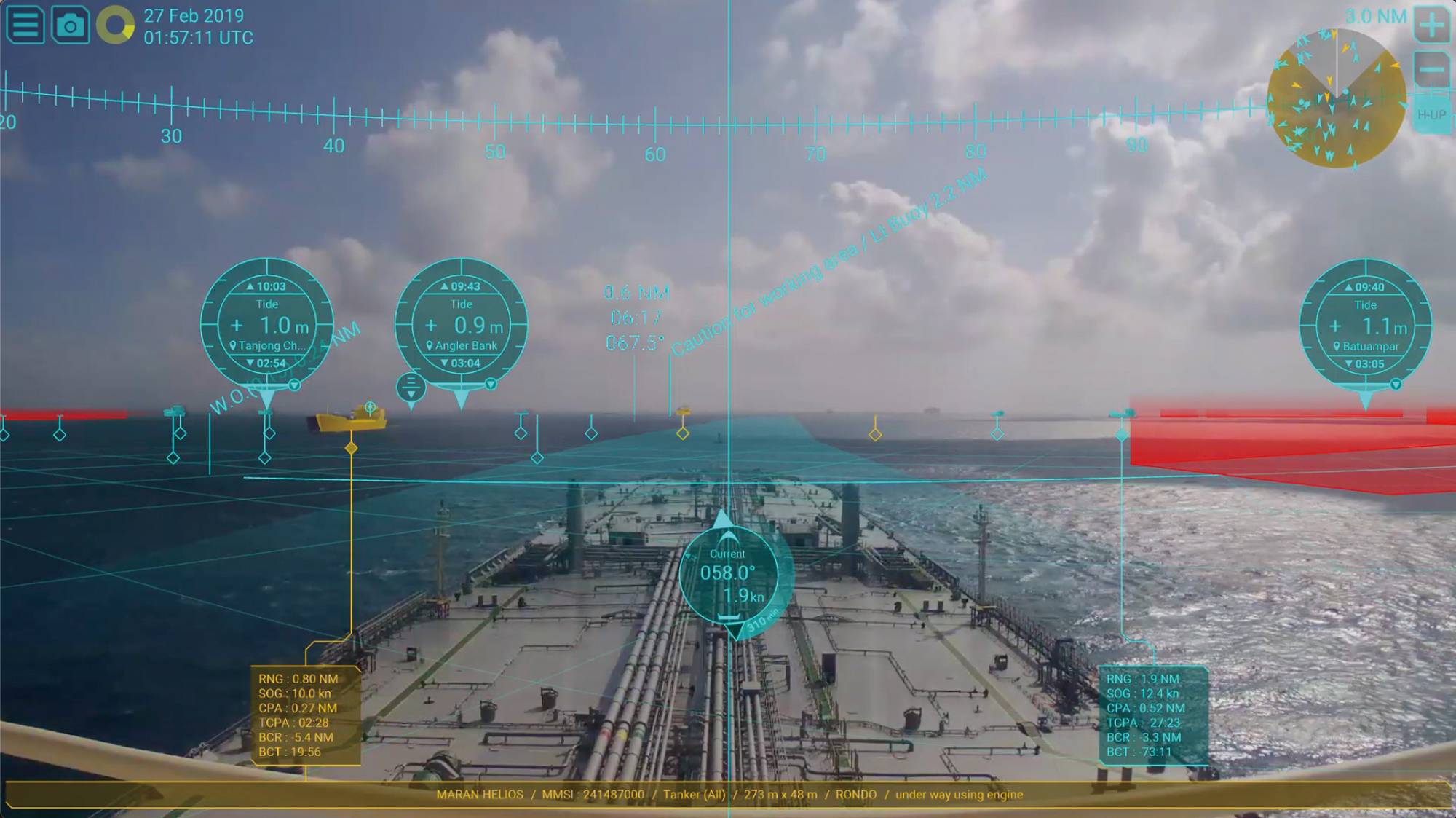

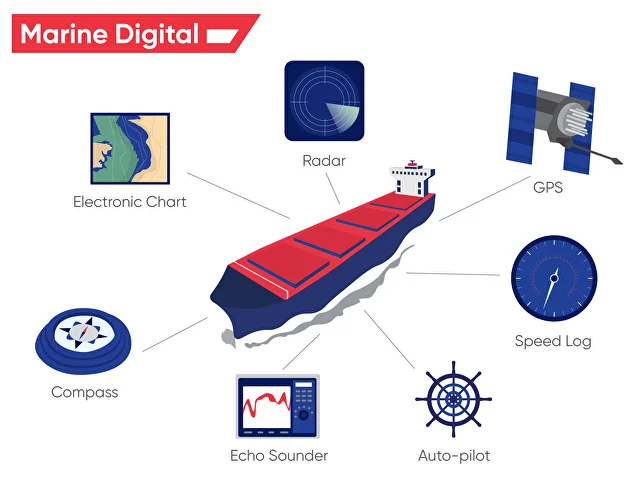

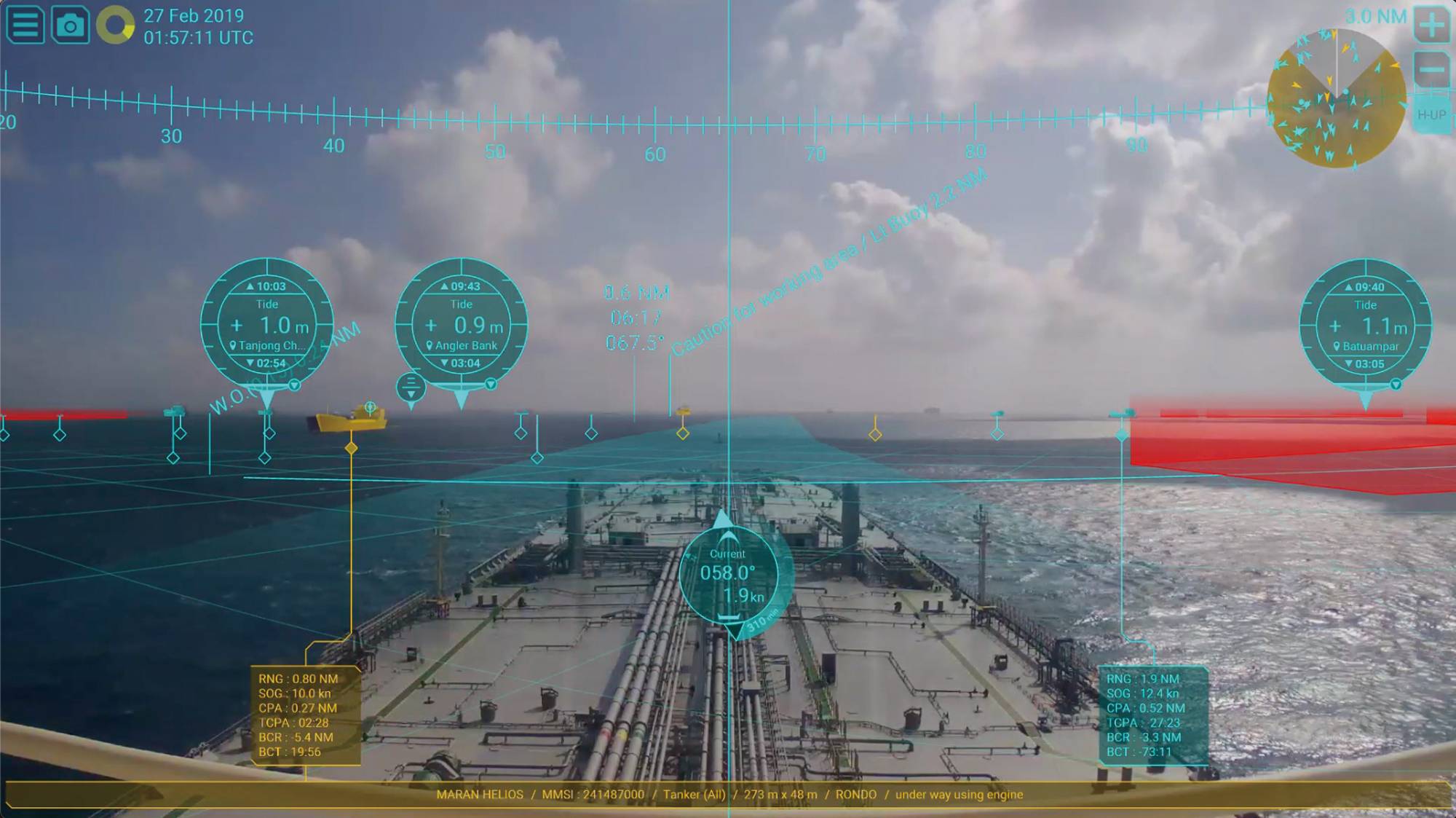

Every safe sea passage begins with a watchkeeper’s awareness. On a modern ship’s bridge, this awareness no longer comes from a single compass bearing or a lone radar screen, but from a continuous stream of information generated by navigational equipment. Radar echoes, electronic charts, satellite positions, AIS targets, gyro headings, depth readings, and visual cues together form a living picture of the ship’s situation.

Maintaining a safe navigational watch today is therefore not about using equipment, but about using information—correctly, critically, and continuously. The ability to integrate data from multiple navigational systems is now a core professional skill for deck officers and masters, directly linked to collision avoidance, grounding prevention, and compliance with international regulations.

Why This Topic Matters for Maritime Operations

Failures in navigational watchkeeping remain a leading causal factor in maritime accidents worldwide. Investigations repeatedly show that the equipment was working, alarms were available, and information was present—yet not correctly interpreted or cross-checked. Understanding how to use navigational equipment information as a decision-support system, rather than as isolated tools, is therefore fundamental to safe operations, professional seamanship, and regulatory compliance.

Regulatory and Professional Foundations of Navigational Watchkeeping

International Standards for Watchkeeping

The framework for navigational watchkeeping is established under the International Maritime Organization through SOLAS, COLREG, and the STCW Convention. These instruments define not only what equipment must be carried, but also how information must be used to maintain a proper lookout by sight, hearing, and all available means.

STCW, in particular, emphasises competence in information assessment, situational awareness, and decision-making. This reflects a shift from equipment-centred compliance to human-centred safety performance.

Industry Guidance and Best Practice

Organisations such as the International Chamber of Shipping and investigation authorities like the Marine Accident Investigation Branch consistently highlight that poor integration of navigational information—rather than equipment failure—is a dominant risk factor in collisions and groundings.

The Modern Bridge as an Information Environment

From Individual Instruments to Integrated Systems

Historically, navigational equipment functioned independently: the radar showed targets, the chart showed position, and the compass gave heading. Today, Integrated Bridge Systems (IBS) and Integrated Navigation Systems (INS) merge data streams into a unified display.

However, integration does not remove responsibility. It increases it. Officers must understand how data is generated, its limitations, and how system failures or sensor errors propagate across multiple displays.

Situational Awareness as the Core Objective

The ultimate goal of using navigational equipment information is situational awareness: knowing where the ship is, where it is going, what surrounds it, and how that situation will evolve in time. Equipment provides inputs, but situational awareness is a human cognitive process.

Key Navigational Equipment and Their Information Contributions

Radar and ARPA: Understanding Motion and Risk

Radar remains the primary collision-avoidance sensor. Modern ARPA systems automatically track targets, calculate Closest Point of Approach (CPA), and Time to CPA (TCPA). These values, however, are only as reliable as the inputs—gyro accuracy, speed data, and target stability.

Effective watchkeepers treat ARPA data as decision support, not as absolute truth. They cross-check radar information with visual bearings, AIS data, and ECDIS predictions, maintaining a healthy level of professional scepticism.

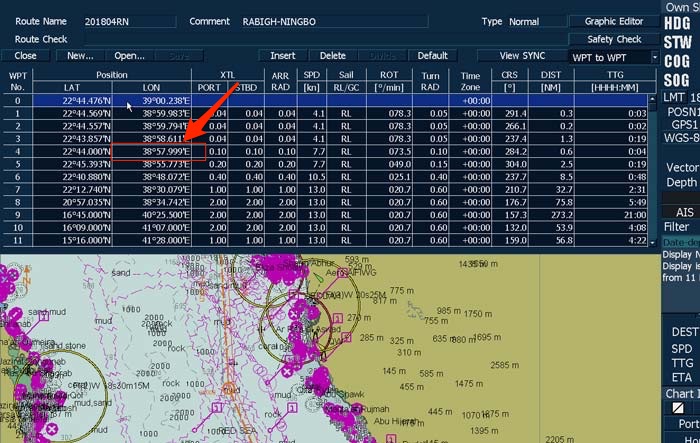

Electronic Chart Display and Information Systems (ECDIS)

Yet, ECDIS-related accidents often stem from overreliance and misconfiguration. Incorrect safety depth settings or misunderstood alarm logic can create a false sense of security. Competent watchkeeping requires officers to understand why an alarm activates, not merely to acknowledge it.

Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS)

GNSS receivers provide continuous, precise position information. However, signal interference, spoofing, or antenna faults can degrade accuracy. Best practice therefore demands position verification using alternative means, including radar ranges, visual bearings, and echo sounders—especially in confined waters.

Automatic Identification System (AIS)

AIS enhances situational awareness by sharing identity, position, course, and speed between vessels. While invaluable for traffic awareness, AIS data is manually entered and not always reliable. Watchkeepers must therefore avoid treating AIS as a substitute for radar or visual lookout.

Gyrocompass, Speed Log, and Sensors

Heading and speed inputs underpin almost all navigational calculations. A small gyro error can distort ARPA predictions and ECDIS overlays. Regular monitoring of sensor performance is therefore part of maintaining a safe watch, not a technical afterthought.

Human Factors in the Use of Navigational Information

Information Overload and Cognitive Bias

Modern bridges can overwhelm watchkeepers with data. Alarms, layers, targets, and numerical readouts compete for attention. Under stress or fatigue, officers may focus on one display and unconsciously ignore others—a phenomenon well documented in accident investigations.

Effective watchkeeping involves selective attention: knowing which information matters most at each phase of navigation, and consciously stepping back to reassess the overall picture.

Bridge Resource Management (BRM)

BRM principles emphasise shared situational awareness, challenge-and-response communication, and workload management. Navigational information must be shared, discussed, and verified within the bridge team, particularly during pilotage, restricted visibility, or high-traffic situations.

Challenges and Practical Solutions in Using Navigational Equipment Information

One major challenge is complacency driven by automation. When systems perform reliably for long periods, officers may stop actively questioning the data. Practical solutions include procedural cross-checks, regular manual position fixing, and active verbalisation of navigational intentions during the watch.

Another challenge lies in inconsistent training quality. While equipment carriage is standardised under SOLAS, competence levels vary widely. Simulator-based training, aligned with STCW and supported by classification societies such as DNV and Lloyd’s Register, is increasingly recognised as essential for bridging this gap.

Case Studies and Real-World Applications

Collision in Coastal Waters

In several investigated collisions, radar and AIS information clearly indicated a developing close-quarters situation. However, officers misinterpreted CPA values due to incorrect speed inputs and failed to visually verify target movement. These cases demonstrate that having information is not the same as understanding it.

Grounding in Confined Waters

Groundings often occur despite ECDIS alarms being available. Investigations reveal that safety contours were set incorrectly or that officers assumed the system would “protect” the vessel. Simulator replays of such incidents are now widely used in training to reinforce the limits of automation.

Future Outlook and Maritime Trends

Digitalisation and Decision Support

Future bridges will increasingly incorporate predictive analytics, integrating weather routing, traffic density, and vessel performance into navigational decision-making. The challenge will not be access to information, but ensuring that humans remain capable of understanding and questioning automated recommendations.

Resilience and Backup Navigation

With growing concern over GNSS vulnerability, renewed emphasis is being placed on resilient navigation—radar navigation, visual pilotage skills, and alternative positioning methods. This trend reinforces the principle that safe navigation depends on multiple, independent sources of information.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does “all available means” mean in watchkeeping?

It means using visual lookout, radar, ECDIS, AIS, sound signals, and any other relevant information together.

Is ECDIS sufficient on its own for safe navigation?

No. ECDIS must always be cross-checked with radar, visual observations, and other sensors.

Why do accidents occur when equipment is working?

Because information is misunderstood, ignored, or not integrated into decision-making.

How does STCW address navigational information use?

STCW focuses on competence in assessment, decision-making, and situational awareness—not just equipment operation.

Can simulators improve navigational watchkeeping?

Yes. Simulator-based training exposes officers to complex, high-risk scenarios without real-world consequences.

Is AIS reliable for collision avoidance?

AIS is a valuable aid, but it must never replace radar and visual lookout.

Conclusion

The use of information from navigational equipment lies at the heart of safe navigational watchkeeping. Modern ships are rich in data, but safety depends on the human ability to integrate, question, and apply that information wisely. Regulations, technology, and training all point toward the same conclusion: navigational safety is not achieved by equipment alone, but by informed, alert, and professionally competent watchkeepers.

For maritime professionals and training institutions alike, strengthening skills in information use—not just equipment operation—is one of the most effective investments in safer seas.

References

International Maritime Organization (IMO). SOLAS Convention.

International Maritime Organization (IMO). STCW Convention and Code.

International Maritime Organization (IMO). COLREGs.

International Chamber of Shipping (ICS). Bridge Procedures Guide.

Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB). Annual Reports and Safety Studies.

DNV. Integrated Bridge System Guidance.

Lloyd’s Register. Navigation and Bridge Ergonomics Publications.

UNCTAD. Review of Maritime Transport.