(With Average Discharge, plus Shipping, Fisheries, Deltas, Ports, and Hydropower Impacts)

Large rivers are not only hydrological “pipes” to the ocean. They are logistics corridors, food systems, and ecosystem engineers. Their freshwater, sediment, and nutrient delivery shapes coastal salinity, fisheries productivity, delta stability, and even the location and competitiveness of ports. At the same time, dams, diversions, dredging, and climate variability can radically change how each river interacts with its receiving sea.

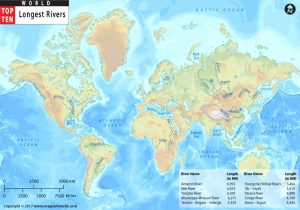

To keep the list technically consistent, the ranking below uses average discharge (m³/s) and focuses on primary rivers that flow directly into a sea or ocean (not tributaries). Discharge values come from widely used global discharge compilations.

Ranked list by average discharge (m³/s)

-

Amazon → Atlantic Ocean — 224,000

-

Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna (GBM) → Bay of Bengal — 42,800

-

Congo → Atlantic Ocean — 41,400

-

Orinoco → Atlantic Ocean — 39,000

-

Yangtze (Chang Jiang) → East China Sea — 31,900

-

Mississippi → Gulf of Mexico — 21,300

-

Yenisei → Kara Sea (Arctic Ocean) — 20,200

-

Lena → Laptev Sea (Arctic Ocean) — 18,300

-

St. Lawrence → Gulf of St. Lawrence (Atlantic) — 17,600

-

Mekong → South China Sea — 15,856

-

Irrawaddy (Ayeyarwady) → Andaman Sea — 15,112

-

Ob → Gulf of Ob (Arctic Ocean) — 13,100

1) Amazon River (Atlantic Ocean) — 224,000 m³/s

The Amazon is the planet’s dominant freshwater source to the ocean. Its discharge creates a vast low-salinity zone and a major plume system that influences stratification, nutrient mixing, and marine productivity across the western tropical Atlantic. The plume is not just a coastal feature; it can extend offshore and seasonally reshape ocean conditions over large distances.

From a logistics standpoint, the Amazon is also an inland sea-like corridor, enabling navigation deep into the continent and supporting river ports that serve industrial supply chains, agriculture, and regional consumer markets. River depth and seasonality matter: high-water seasons improve navigability, while low-water periods can constrain drafts and disrupt schedules—an increasingly material risk under climate variability.

Dams in parts of the basin alter sediment pulses and seasonal flows, affecting floodplain ecology and the sediment balance that supports deltaic and nearshore habitats. Where sediment delivery declines, coastal and delta systems can become more vulnerable to erosion and saltwater intrusion.

2) Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna (Bay of Bengal) — 42,800 m³/s

The GBM system drives one of the world’s largest delta environments, where freshwater and sediment delivery forms a dynamic interface between inland economies and the Bay of Bengal. This is an archetypal “river-to-sea coupling” case: river discharge supports highly productive coastal fisheries and estuarine ecosystems, while also creating complex navigation conditions through sedimentation, shifting channels, and cyclone-driven coastal change.

Inland shipping and riverine logistics are central to regional connectivity, but the same sediment loads that build land can also increase dredging requirements for ports and approaches. Dams and upstream interventions can reduce sediment reaching the delta over time, potentially increasing coastal vulnerability and altering nursery habitats that underpin fisheries.

3) Congo River (Atlantic Ocean) — 41,400 m³/s

The Congo is exceptional not only for discharge but also for the stability of flow across seasons due to its basin spanning both hemispheres. Its freshwater delivery strongly influences coastal salinity and nearshore ecosystems, while the river also transports significant sediment loads into the Atlantic, contributing to marine nutrient dynamics and seabed processes.

From a development standpoint, the Congo basin’s hydropower potential is enormous, and large-scale projects are frequently discussed in regional energy strategies. Hydropower and navigation priorities can conflict: altering flow regimes and sediment transport can change channel morphology, affecting navigability and river-dependent livelihoods such as fisheries.

4) Orinoco River (Atlantic Ocean) — 39,000 m³/s

The Orinoco is a defining river-ocean system for northern South America. Its delta and estuarine mixing zone shape coastal productivity and support fishing and biodiversity-rich wetlands. Economically, the river functions as a strategic corridor for inland movement of bulk commodities and industrial goods, linking interior regions to Atlantic-facing maritime trade routes.

Like other deltaic systems, it is sensitive to upstream land-use change, dredging practices, and flow modifications that may alter sediment delivery—key to maintaining delta stability and coastal habitats.

5) Yangtze (East China Sea) — 31,900 m³/s

The Yangtze is among the world’s most important river logistics arteries, connecting interior industrial regions with major coastal ports and global shipping networks. Its river-to-sea interface influences coastal sedimentation patterns and estuarine ecosystems in the East China Sea.

Hydropower and navigation engineering are central features of the Yangtze system. The Three Gorges Dam plays a multi-purpose role in power generation, flood control, and navigation improvement, while also reshaping downstream sediment and ecological conditions.

6) Mississippi (Gulf of Mexico) — 21,300 m³/s

The Mississippi is a classic case of a high-discharge river whose nutrient delivery has major marine consequences. Nutrient runoff transported downriver contributes to seasonal hypoxia dynamics in the Gulf of Mexico, illustrating how river basin land use can directly affect coastal marine ecology and fisheries.

Logistically, the Mississippi system is a backbone for North American inland waterway freight—particularly bulk commodities—feeding major river ports and connecting to deep-sea export routes through the Gulf. Dams and locks improve navigability, but they also change natural flow timing and sediment dynamics, which can influence delta stability and coastal wetland loss trends.

7) Yenisei (Kara Sea, Arctic Ocean) — 20,200 m³/s

The Yenisei is one of the largest Arctic-draining rivers, delivering massive freshwater volumes into the Kara Sea. This freshwater input can strongly affect sea-ice formation processes, stratification, and coastal ecosystem structure—issues that are gaining new relevance as Arctic shipping seasons lengthen.

The river’s logistics relevance is often tied to seasonal windows, ice conditions, and the integration of river transport with Arctic port operations. Energy infrastructure in Siberia also intersects with river systems, increasing the importance of safe navigation, spill prevention, and environmental monitoring in sensitive Arctic receiving waters.

8) Lena (Laptev Sea, Arctic Ocean) — 18,300 m³/s

The Lena is another dominant Arctic freshwater source. Its seasonal pulse is extreme, and the spring/summer freshet delivers large freshwater and sediment loads to the Laptev Sea. Ecologically, this influences nearshore productivity and habitat conditions, while also affecting sedimentation at the river mouth.

For inland shipping, the Lena’s navigability is heavily seasonal. The operational challenge is not only ice, but also water level variability and the constraints of remote logistics chains. In the Arctic context, river ports function as essential lifelines for regional supply and resource projects.

9) St. Lawrence (Gulf of St. Lawrence, Atlantic) — 17,600 m³/s

The St. Lawrence is distinctive because it is both a major river outflow system and a managed deep-draft navigation corridor connecting the Atlantic to the Great Lakes industrial heartland. The Great Lakes–St. Lawrence Seaway system enables oceangoing navigation far inland via locks, channels, and engineered waterways.

This makes the St. Lawrence a premier example of river maritime economics: ports along the corridor support bulk trades such as grain and industrial cargoes, and disruptions can have immediate supply chain impacts across a wide hinterland. The river’s estuarine ecology is also complex, with mixing zones and habitats sensitive to temperature change, invasive species, and altered freshwater timing.

10) Mekong (South China Sea) — 15,856 m³/s

The Mekong is among the most socio-economically consequential rivers on Earth due to the scale of agriculture, fisheries, and delta livelihoods it supports. Its delta’s stability depends heavily on sediment delivery, yet multiple drivers—including upstream hydropower dams and intensive sand mining—are associated with declining sediment supply and rising vulnerability to subsidence and saltwater intrusion.

From a maritime perspective, the Mekong delta is also a logistics landscape: inland waterways, river ports, and coastal shipping interfaces support regional trade flows. When sediment loads change, the consequences propagate into navigation channels, dredging requirements, and estuarine habitat quality—directly affecting fisheries and aquaculture productivity.

11) Irrawaddy (Andaman Sea) — 15,112 m³/s

Myanmar’s Irrawaddy is the country’s central river system, supporting inland navigation networks, delta agriculture, and fisheries that depend on the river’s seasonal rhythm. The river-to-sea interface in the Andaman Sea region supports mangrove-associated ecosystems and coastal fisheries that are sensitive to changes in sediment delivery and salinity intrusion.

Large dam proposals in the basin highlight a common trade-off: hydropower can strengthen energy security, but flow alteration and sediment trapping can reshape downstream delta geomorphology and estuarine habitat health—often with direct impacts on fisheries and coastal protection.

12) Ob (Gulf of Ob, Arctic Ocean) — 13,100 m³/s

The Ob is a major Arctic-draining river system with strong relevance to both climate-ocean interactions and resource logistics. Large freshwater discharge into the Gulf of Ob influences coastal stratification and can affect ice dynamics and nearshore marine ecosystems—factors increasingly important as Arctic shipping and energy development evolve.

Inland shipping here is shaped by seasonality, ice constraints, and long distances. The river functions as a transport spine for regional communities and industrial supply chains, while the receiving Arctic waters require high environmental safeguards due to limited response capacity and sensitive ecosystems.

Cross-cutting themes that matter for maritime stakeholders

Inland shipping and logistics value

Across these rivers, inland waterways reduce transport costs for bulk cargoes and connect interior economies to global trade. Where rivers are engineered for navigation, reliability improves—but environmental trade-offs often intensify, especially around sediment continuity and habitat fragmentation.

Ports at river mouths and estuaries

Many of the world’s most strategic ports sit on estuaries because they combine deep-water access with hinterland penetration. However, estuaries are dynamic systems where sedimentation, salinity intrusion, and sea-level rise can raise operational and infrastructure risks.

Fisheries and food security linkage

High-discharge rivers often fertilize coastal seas, supporting productive fisheries until nutrient loading becomes excessive and ecosystem stress emerges.

Dams, hydropower, and sediment trade-offs

Hydropower dams improve flood control and navigation upstream but can trap sediment and flatten seasonal flow peaks. Over time, reduced sediment delivery can weaken deltas and increase vulnerability to erosion and storm surges.

🚢 The following table synthesizes the key interconnections between your identified themes, highlighting their primary drivers and the critical trade-offs they present for stakeholders.

| Cross-Cutting Theme | Economic & Strategic Value | Key Risks & Environmental Trade-offs | Current Trends & Management Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inland Shipping & Logistics Value | High-capacity, low-cost transport; Critical for intermodal supply chains; Global market valued at ~$1.7 trillion. | Subject to cost fluctuations (e.g., fuel prices); Inland bottlenecks can cascade from port delays. | Rise of automation & IT platforms for vessel management; Growth of integrated end-to-end logistics. |

| Ports at River Mouths & Estuaries | Strategic hubs combining deep-water access with hinterland connectivity; Handle >90% of global trade. | Highly exposed to climate risks: sea-level rise, storm surges, sedimentation. | Investing in adaptive measures (e.g., elevation, drainage); Using advanced modeling for vulnerability assessments. |

| Dams, Hydropower & Sediment | Provide flood control, water security, and renewable energy. | Fragment rivers, trap sediments, and block fish migration; In the US, >50,000 dams have reversed natural fragmentation patterns. | Growing focus on strategic dam planning, sediment management, and barrier removal; EU aims to restore 25,000 km of free-flowing rivers by 2030. |

| Fisheries & Food Security | Coastal fisheries fertilized by river discharges support livelihoods and food security. | Dam-induced sediment/nutrient cuts can reduce coastal productivity; Excessive nutrient loading from other sources causes ecosystem stress. | (Emerging) Linkage with strategic dam placement and sediment management to protect critical fish habitats. |

🔗 Deeper Dive into Critical Interconnections

–

End Reference List (with links)

-

List of rivers by discharge (average discharge ranking):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_rivers_by_discharge -

Great Lakes–St. Lawrence Seaway System (official overview):

https://www.seaway.dot.gov/about/great-lakes-st-lawrence-seaway-system -

Three Gorges Dam – hydropower and navigation overview (USGS):

https://www.usgs.gov/water-science-school/science/three-gorges-dam-worlds-largest-hydroelectric-plant -

NOAA overview of Mississippi River nutrient runoff and Gulf hypoxia:

https://www.noaa.gov/news-release/gulf-of-america-dead-zone-below-average-scientists-find -

Mekong River sediment and dam impacts (peer-reviewed literature):

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0048969720359970 -

Vietnamese Mekong Delta subsidence and sediment decline (open access):

https://www.mdpi.com/2072-4292/13/2/189 -

Amazon River plume and ocean interaction (open-access marine science):

https://www.mdpi.com/2077-1312/12/6/851