Discover the fascinating world of hermit crabs and their unique shell exchange behavior. Learn how these small crustaceans choose, swap, and compete for shells, what this reveals about marine ecosystems, and why their story matters for ocean science, maritime education, and conservation.

Why Hermit Crabs Capture Our Imagination

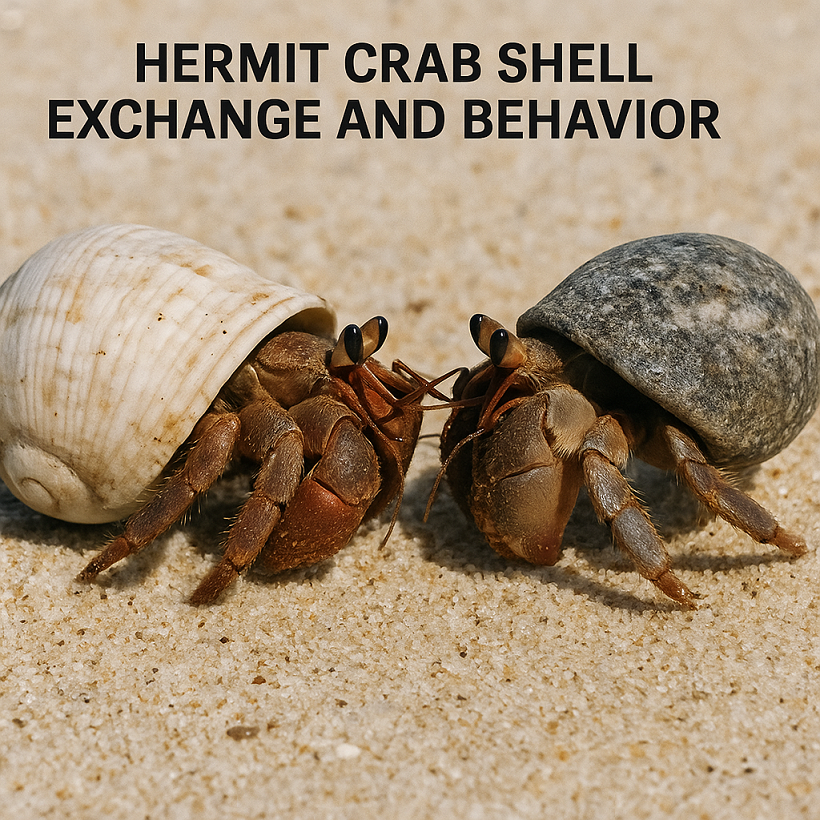

On many tropical beaches and rocky coasts, children and scientists alike marvel at hermit crabs. Unlike most crabs, hermit crabs don’t grow their own protective shells. Instead, they borrow them from snails and other gastropods. This quirky lifestyle has made them famous as “the renters of the sea.”

On many tropical beaches and rocky coasts, children and scientists alike marvel at hermit crabs. Unlike most crabs, hermit crabs don’t grow their own protective shells. Instead, they borrow them from snails and other gastropods. This quirky lifestyle has made them famous as “the renters of the sea.”

But hermit crab shell exchange is more than a curiosity. It is a window into marine ecology, evolutionary biology, and even human-like negotiation strategies. Their behavior reveals how limited resources shape survival. Watching hermit crabs form queues or engage in tug-of-war over shells provides lessons in cooperation, conflict, and adaptation that resonate far beyond tidepools.

For maritime professionals, educators, and ocean enthusiasts, understanding hermit crab behavior is more than just marine trivia—it highlights how small species reflect big ecological truths.

Primary keywords: hermit crab shell exchange, hermit crab behavior, marine ecology, shell selection.

Secondary keywords: crustacean adaptation, intertidal ecosystems, marine biodiversity, ocean conservation.

The Biology of Hermit Crabs

Anatomy and Adaptation

Hermit crabs belong to the superfamily Paguroidea. Unlike “true crabs,” their abdomens are soft and spiraled, leaving them vulnerable to predators. Nature solved this weakness with an ingenious strategy: occupy empty snail shells.

Their curved abdomens fit neatly into spiraled shells, and specialized appendages (called uropods) anchor them inside. Over evolutionary time, hermit crabs have become so dependent on shells that they rarely survive long without one.

Marine vs. Terrestrial Hermit Crabs

Hermit crabs aren’t all the same. More than 1,100 species exist worldwide, split between marine and terrestrial environments:

-

Marine hermit crabs inhabit coral reefs, rocky shores, and sandy bottoms.

-

Terrestrial hermit crabs (like the Caribbean Coenobita clypeatus) spend most of their lives on land but still need saltwater to reproduce.

Both rely on shells for survival, but terrestrial species often carry shells for decades, making exchange behaviors even more dramatic.

Why Shells Matter

Protection and Survival

A shell is more than a house—it is life insurance. A suitable shell protects hermit crabs from predators, desiccation, and even strong waves.

Studies published in Marine Ecology Progress Series show that hermit crabs in poorly fitting shells have higher predation rates and reduced reproductive success.

Growth and Energy Efficiency

As hermit crabs grow, their shells become too small. Living in a cramped shell means wasted energy, slower growth, and even shell-induced deformities. Conversely, an oversized shell is heavy and inefficient.

This balance—between safety, growth, and energy—drives the constant search for the “perfect fit.”

The Art of Shell Exchange

How Hermit Crabs Evaluate Shells

When a new shell appears (often left behind by a dead snail), hermit crabs don’t rush blindly inside. They:

-

Inspect the shell’s size, weight, and opening.

-

Rotate it with their pincers.

-

Sometimes even test drive the shell by slipping halfway inside before deciding.

The Famous “Shell Queue” Phenomenon

One of the most remarkable behaviors is synchronous shell exchange, first documented by researchers at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. When a desirable shell arrives, hermit crabs gather in a line, ranked by size.

The largest crab takes the new shell, leaving its old one behind. The next crab moves into the vacated shell, and so on—like an orderly housing chain.

This queue system prevents fights and ensures efficient shell distribution. Yet, fights still occur if a shell is rare or especially high quality.

Aggressive vs. Cooperative Strategies

Shell exchanges are not always peaceful. Studies in the Journal of Crustacean Biology describe agonistic behaviors, where crabs drum on shells to evict current occupants. Some even forcefully extract rivals.

This mix of cooperation and conflict makes hermit crab societies an ideal model for studying negotiation and resource sharing in nature.

Case Studies: Lessons from the Field

Coral Reef Hermit Crabs in Decline

On Caribbean reefs, marine biologists from NOAA have observed declining hermit crab populations linked to ocean acidification. Acidic waters reduce snail shell availability, leaving crabs shell-less and vulnerable.

Terrestrial Hermit Crabs and Plastic Pollution

On remote Pacific islands, terrestrial hermit crabs face a bizarre new challenge: plastic debris. A 2019 study in Journal of Hazardous Materials reported that hermit crabs mistakenly occupy bottle caps and plastic tubes, often with fatal results.

These cases highlight how global environmental changes ripple down to the smallest creatures.

Human Connections: Why This Matters for Maritime Education

Ecosystem Engineers

By scavenging shells and recycling organic matter, hermit crabs play a role as ecosystem engineers, maintaining intertidal balance.

Indicators of Environmental Stress

Hermit crab populations are also bioindicators. Their shell availability, population density, and exchange behaviors reveal broader ecological health. For maritime professionals, such species offer early warning signs of coastal stressors.

Educational Value

In maritime education, hermit crabs serve as engaging entry points to teach about:

-

Resource competition in marine ecosystems.

-

Adaptation and survival strategies.

-

Human impacts like pollution and overfishing of gastropods.

Challenges and Threats

Climate Change and Ocean Acidification

The IPCC Special Report on the Ocean (2021) warns that rising acidity weakens snail shells. With fewer shells available, hermit crabs face survival bottlenecks.

Overharvesting of Gastropods

In some coastal economies, gastropods are harvested for food and ornaments. This reduces the shell supply chain critical for hermit crabs.

Tourism and Pet Trade

The global pet trade removes millions of terrestrial hermit crabs from beaches annually. Often sold without proper shells, many die prematurely, disrupting local populations.

Future Outlook: What Can Be Done?

-

Sustainable coastal management can protect gastropod populations, indirectly supporting hermit crabs.

-

Marine protected areas (MPAs) help secure habitats where shell resources remain stable.

-

Public education campaigns, such as those led by the Marine Biological Association, raise awareness about not collecting live shells.

-

Research innovations: Some conservationists experiment with 3D-printed biodegradable shells to supplement shortages.

FAQ: Hermit Crab Shell Exchange and Behavior

Do hermit crabs kill snails for shells?

Most rely on shells left behind by dead snails. However, competition may lead to aggression, but direct predation on snails is rare.

Why do hermit crabs line up to exchange shells?

It’s a cooperative strategy to ensure everyone gets a suitable shell, reducing the risk of fights.

Can hermit crabs survive without shells?

Not for long. Without shells, they dehydrate, face predation, and die within hours to days.

Do hermit crabs feel pain when forced out of shells?

Research suggests crustaceans show responses consistent with pain perception, making forced eviction stressful.

How does pollution affect hermit crabs?

Plastic waste often substitutes for natural shells, leading to injuries or death. Pollution also reduces gastropod populations.

Why are hermit crabs important to study?

They provide insights into resource competition, cooperation, and environmental health—lessons relevant to both ecology and maritime management.

Conclusion: Tiny Teachers of the Ocean

Hermit crabs may be small, but their behaviors echo big ecological truths. From their inventive use of shells to their cooperative exchanges, they embody resilience, adaptability, and the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

For maritime students, seafarers, and enthusiasts, hermit crabs remind us that even the smallest mariners carry lessons for sustainability, resource sharing, and survival in a changing ocean.

References

-

Hazlett, B. A. (1981). The behavioral ecology of hermit crabs. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics.

-

Laidre, M. E. (2012). Homes for hermits: Evolution of architecture in hermit crabs. Ecology Letters.

-

NOAA Fisheries. (2021). Climate impacts on marine species. Link

-

IPCC. (2021). Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. Link

-

O’Hara, T. et al. (2019). Plastic pollution and terrestrial hermit crabs. Journal of Hazardous Materials.

-

Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. Hermit crab shell exchange behavior. Link

-

Marine Biological Association (UK). Marine education resources. Link