Venezuela as a Maritime Energy State

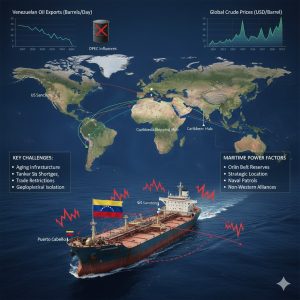

Venezuela’s contemporary economic reality cannot be understood without examining its relationship with the sea. Although the country possesses the largest proven oil reserves in the world, its ability to convert underground resources into economic value depends almost entirely on maritime transport. In 2025, Venezuela is not simply an oil producer; it is a maritime-dependent energy state, whose survival under prolonged sanctions is determined by ports, tankers, shipping routes, logistics networks, and maritime risk management.

Unlike landlocked producers or pipeline-dominant exporters, Venezuela relies overwhelmingly on seaborne trade. More than ninety percent of its crude oil and refined product exports move by ship, primarily through the Caribbean Sea and onward to global markets. As a result, U.S. sanctions, infrastructure decay, and geopolitical isolation manifest first and most clearly in the maritime domain.

This article integrates all major dimensions of Venezuela’s maritime energy system—oil exports, ports and terminals, shipping routes, sanctions-driven logistics, commercial fleets, and naval and coast guard roles—to present a holistic picture of how Venezuela continues to function as an oil exporter in a fragmented global economy.

1. Venezuelan Oil Exports in a Maritime Context

Venezuela’s oil export profile is defined by heavy and extra-heavy crude grades, particularly blends derived from the Orinoco Belt. These crudes require dilution, specialised handling, and compatible refinery configurations, which narrows the pool of potential buyers and directly influences shipping patterns.

In 2025, Venezuelan oil exports are substantially lower than their historical peak, but they remain strategically relevant. Exports are no longer optimised for efficiency or proximity; instead, they are shaped by political tolerance, logistical flexibility, and maritime risk acceptance. Asian markets—especially China—have become the dominant destination, often reached through indirect trade structures and complex shipping arrangements.

From a maritime perspective, Venezuelan oil is characterised by longer voyage distances, higher freight intensity, and increased reliance on transshipment. The same barrel of oil now requires more ship-days, more insurance negotiation, and more logistical coordination than it did a decade ago. This inefficiency is not accidental; it is the structural consequence of sanctions operating through shipping and finance rather than through international law.

2. Ports, Terminals, and Coastal Infrastructure

Venezuela’s oil exports are concentrated at a small number of coastal facilities, most notably the Jose terminal in Anzoátegui, the Paraguaná complex at Amuay and Punta Cardón, Puerto La Cruz, and El Palito. These ports form the physical interface between Venezuelan oil production and global maritime trade.

Over time, these facilities have become strategic bottlenecks. Aging infrastructure, power instability, limited spare parts, and constrained maintenance capabilities have reduced effective throughput well below nominal capacity. Draft limitations and loading constraints mean that very large tankers cannot always be accommodated directly, particularly under degraded operating conditions.

As a result, Venezuela increasingly relies on offshore ship-to-ship transfers to consolidate cargoes. These operations effectively extend port functionality into international waters, allowing Aframax-sized parcels to be combined into larger Suezmax or VLCC shipments. While operationally effective, this approach increases environmental exposure, navigational risk, and regulatory scrutiny.

Ports, once passive infrastructure, have thus become active determinants of Venezuela’s export capacity, shaping tanker selection, routing decisions, and commercial viability.

3. Maritime Routes and Shipping Corridors

Venezuelan oil exports move primarily through the Caribbean Sea before connecting to wider Atlantic and transoceanic routes. Historically, short-haul voyages to the U.S. Gulf Coast dominated. Today, those routes have largely disappeared, replaced by long-haul maritime corridors toward Asia.

These new routes often involve intermediate transshipment points, indirect ownership chains, and extended voyages around major chokepoints. From a shipping economics perspective, this has increased tonne-mile demand while simultaneously fragmenting the tanker market.

The Caribbean Sea’s relatively low militarisation compared to the Persian Gulf reduces the risk of direct naval confrontation, but this does not equate to low risk. Surveillance, compliance pressure, and commercial exclusion operate continuously, forcing shipping decisions to prioritise discretion and flexibility over efficiency.

4. Buyers, Trade Structures, and Maritime Intermediation

Venezuela’s buyer base has narrowed significantly, not because of crude quality alone, but because of the legal and financial exposure associated with U.S. sanctions. The remaining buyers are characterised by political alignment, refinery compatibility, and tolerance for delivery uncertainty.

In practice, Venezuelan oil is often sold through intermediaries rather than directly to end-users. This layered trade structure introduces additional maritime complexity. Chartering arrangements are short-term and opportunistic, vessel ownership is fragmented, and documentation flows are opaque.

Shipping, in this context, is not a neutral transport service but a strategic intermediary, shaping who can buy Venezuelan oil and at what cost.

5. Tanker Types, Flags, and the Segmented Shipping Market

Venezuela’s oil exports are carried predominantly by Aframax and Suezmax tankers, with VLCCs appearing primarily after offshore consolidation. The vessels involved are typically older than the global fleet average and frequently reflagged.

Flags of convenience dominate, reflecting the need for regulatory flexibility and insulation from enforcement pressure. Ownership structures are often opaque, involving special-purpose entities and offshore jurisdictions.

This has placed Venezuelan trade within a broader phenomenon of segmented tanker markets, where certain vessels are effectively excluded from mainstream trades and instead specialise in politically sensitive or sanctioned cargoes. This segmentation reduces overall market efficiency and raises freight costs globally.

6. Sanctions, Logistics, and Maritime Adaptation

Venezuela is not subject to UN sanctions prohibiting oil exports. The constraints shaping its maritime trade arise almost entirely from U.S. unilateral and secondary sanctions, enforced through financial systems, insurance markets, and commercial deterrence.

Shipping Venezuelan oil remains legal under international maritime law, yet commercially hazardous. This has driven the development of adaptive logistics strategies, including ship-to-ship transfers, indirect routing, frequent changes in vessel identity, and selective AIS transmission practices.

These adaptations do not eliminate trade but transform it into a parallel maritime logistics system, less transparent, more expensive, and more fragile than conventional energy trade.

7. Risk Management, Insurance, and Compliance Pressure

Insurance has become one of the most powerful choke points in Venezuelan oil shipping. Many mainstream insurers avoid exposure, while others impose restrictive terms, exclusions, or high deductibles. War-risk premiums and compliance clauses fluctuate with political developments rather than operational conditions.

For shipowners and charterers, participation in Venezuelan trades is a continuous risk-pricing exercise. Regulatory exposure, port access elsewhere, reputational impact, and financial settlement risks all factor into voyage decisions.

This environment reinforces the separation between sanctioned and compliant shipping, embedding inefficiency into the global tanker system.

8. Commercial Fleet Decline and Workforce Implications

Venezuela once operated a substantial state-linked commercial fleet. Today, that fleet has largely collapsed. PDVSA’s maritime arm retains limited operational capacity, while much of the country’s shipping expertise has migrated abroad.

The decline of national shipping capacity has forced reliance on foreign tonnage and eroded institutional maritime knowledge. Venezuelan seafarers remain present in global shipping, but increasingly as individuals rather than as part of a coherent national fleet.

This hollowing-out of maritime capability has long-term consequences that extend beyond sanctions relief, affecting fleet renewal, training capacity, and operational resilience.

9. Regional Shipping Networks and Informal Ecosystems

Venezuelan oil exports are embedded within a broader regional shipping ecosystem involving Caribbean ports, storage hubs, and risk-tolerant operators. This network operates largely outside mainstream visibility but is critical to sustaining trade.

These operators specialise in flexibility rather than scale, adapting rapidly to regulatory changes and market signals. While commercially effective in the short term, this ecosystem lacks the stability and redundancy of conventional shipping networks.

10. Maritime Geopolitics and Strategic Positioning

Venezuela’s maritime position is geopolitically significant but not dominant. The country does not control a global chokepoint, yet its exports pass through sea lanes that intersect with U.S., Caribbean, and Atlantic maritime interests.

Unlike Iran, Venezuela lacks the naval capability to influence regional shipping beyond its immediate waters. Its maritime leverage lies not in coercion, but in complicating energy logistics and absorbing geopolitical pressure through shipping adaptation.

11. Navy, Coast Guard, and Maritime Security

Venezuela’s navy and coast guard play a primarily defensive role, focused on protecting ports, terminals, and coastal waters. Their capabilities are modest, constrained by aging platforms and limited resources.

From a shipping perspective, Venezuelan waters present operational and regulatory risks rather than acute security threats. Inspections, delays, and administrative scrutiny are more likely than direct confrontation.

This posture supports export continuity while avoiding escalation, aligning maritime security with economic survival rather than power projection.

12. Implications for Global Shipping and Energy Markets

Venezuela’s maritime experience illustrates a broader truth about modern sanctions: they do not stop trade; they deform it. Oil continues to move, but at higher cost, lower transparency, and greater risk.

For global shipping, this deformation increases freight rates, reduces fleet flexibility, and embeds geopolitical risk into energy prices. For energy markets, it contributes to inflationary pressure and long-term inefficiency.

Conclusion: Venezuela as a Maritime Case Study in a Fragmented World

In 2025, Venezuela is best understood not simply as a sanctioned oil producer, but as a maritime adaptation system. Its economy survives through ports that function under constraint, tankers that operate at the margins of compliance, logistics networks designed for discretion, and a naval posture focused on protection rather than confrontation.

For the global maritime industry, Venezuela offers a clear lesson. When politics restrict markets, the sea becomes the primary space of adaptation. But adaptation comes at a cost—measured in efficiency, transparency, and long-term resilience.

Venezuela’s story is therefore not only about one country. It is about how global energy trade is reshaped when maritime transport becomes the last remaining conduit between resources and markets.