“There once was a ship that put to sea” explained: the real maritime history behind sea shanties, whaling ships, sailor life, and modern shipping lessons.

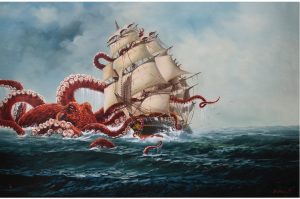

With this simple line, millions of people around the world were drawn—perhaps unknowingly—into the deep cultural memory of maritime history. What sounds like a children’s rhyme or a catchy song lyric is, in fact, an echo of centuries of life at sea: long voyages, dangerous work, tight-knit crews, and the rhythm of labor shaped by wind and waves.

This line opens the famous sea shanty often known as The Wellerman. Its global revival in the digital age surprised even maritime historians, reminding the world that ships are not just steel and engines—they are also stories, voices, and shared human experience. For seafarers, educators, and maritime professionals, this cultural moment offers an opportunity to reconnect modern shipping with its historical roots.

This article explores what “there once was a ship that put to sea” truly represents in maritime terms. It examines the historical context of sailing and whaling ships, the role of sea shanties as operational tools, the realities of life on board, and the lessons these traditions still offer to today’s global maritime industry.

Why This Topic Matters for Maritime Operations

At first glance, a sea shanty may seem far removed from today’s container terminals, digital navigation systems, and international regulations. Yet maritime operations have always depended on people working together under pressure, isolation, and risk. The cultural tools that supported sailors in the past still matter—just in different forms.

Human factors before automation

Before engines, radar, and GPS, ships relied almost entirely on human strength, coordination, and judgment. Every sail hoisted, anchor raised, or cargo handled depended on teamwork. Sea shanties emerged as a practical solution: they synchronized effort, regulated pace, and reduced fatigue. In modern terms, they were an early form of human-factor engineering.

Organizations such as the International Maritime Organization now emphasize human element considerations in safety management systems. While the tools have changed, the underlying challenge—aligning human performance with operational demands—remains the same.

Cultural continuity in global crews

Today’s ships are crewed by multinational teams speaking multiple languages. In the past, crews were also diverse, often drawn from different ports and cultures. Shared songs and routines created cohesion. Understanding this heritage helps explain why communication, morale, and leadership remain central to safe maritime operations.

Education beyond technology

Maritime education is not only about rules and systems; it is also about identity and professional pride. Stories embedded in phrases like “there once was a ship that put to sea” help humanize maritime careers for students and non-specialists, making the industry more accessible to a global audience.

The Ship That Put to Sea: Historical Context

The age of sail and global trade

The phrase “there once was a ship that put to sea” places us firmly in the age of sail, roughly from the 16th to the mid-19th century. During this period, sailing ships connected continents, enabled colonial expansion, and laid the foundations of modern global trade.

Merchant vessels carried timber, grain, spices, and textiles. Naval ships projected power. Whaling ships ventured farther than almost any other vessels, chasing whales across oceans for oil, baleen, and other valuable products.

These ships were not fast by modern standards, but they were robust, adaptable, and entirely dependent on wind and seamanship.

Whaling ships and endurance

The shanty The Wellerman is associated with the whaling trade of the South Pacific, particularly around New Zealand. Whaling voyages could last years. Crews faced extreme weather, isolation, and dangerous manual labor.

A whaling ship was both workplace and home. Every member of the crew, from the captain to the greenest hand, relied on collective discipline. Songs helped impose order on chaos.

Sea Shanties as Maritime Technology

Not entertainment, but a tool

Sea shanties were not sung for pleasure alone. They were functional work songs, matched precisely to specific tasks. A hauling shanty accompanied pulling on ropes. A capstan shanty set the rhythm for raising anchor. The lead singer, or shantyman, adjusted tempo to conditions.

In a way, a shanty was an early “interface” between human energy and ship systems.

Rhythm, safety, and efficiency

By coordinating effort, shanties reduced uneven loading and sudden strain on ropes and fittings. This lowered the risk of injury and equipment failure. Modern safety management recognizes similar principles when emphasizing standardized procedures and clear communication.

Parallels with modern bridge teamwork

On today’s ships, verbal commands, checklists, and alarms replace songs. Yet the objective is identical: ensure that everyone acts together, at the right time, with shared understanding. Bridge Resource Management (BRM), promoted through standards linked to the STCW Convention under the International Maritime Organization, echoes these old lessons in modern form.

Life on Board the Ship That Put to Sea

Daily routine and discipline

Life at sea followed a strict routine. Watches divided the day and night. Meals were simple, repetitive, and often scarce. Discipline was firm, sometimes harsh, but necessary to maintain order on long voyages.

The opening line of a shanty often marked a psychological transition—from shore life to sea life, from individual identity to collective purpose.

Isolation and mental resilience

Months away from land tested sailors’ mental health long before the term existed. Songs, stories, and shared rituals helped maintain morale. In modern shipping, isolation remains a challenge, now addressed through connectivity, welfare standards, and regulations such as the Maritime Labour Convention supported by the International Labour Organization.

Danger as a constant companion

Storms, disease, accidents, and shipwrecks were ever-present threats. A ship that “put to sea” accepted risk as part of its mission. Today’s safety standards, classification rules, and accident investigations—conducted by bodies like the Marine Accident Investigation Branch—exist precisely because of lessons learned through centuries of hardship.

From Song to Viral Phenomenon: Modern Revival

The digital rediscovery

In the early 2020s, The Wellerman resurfaced on social media platforms, reaching audiences far removed from maritime life. The song’s simple structure and call-and-response style resonated during a period of global isolation.

Suddenly, millions were singing about ships, seas, and sailors—often without realizing the historical depth behind the lyrics.

Opportunity for maritime education

This revival created a rare moment when maritime culture entered mainstream conversation. Educators and institutions seized the chance to explain seafaring history, trade routes, and the human side of shipping to new audiences.

For an industry often described as “invisible,” this cultural bridge proved valuable.

Challenges and Practical Solutions

The challenge today is not preserving shanties for nostalgia, but translating their underlying principles into modern maritime practice. Crew fatigue, communication breakdowns, and cultural misunderstanding still contribute to incidents at sea.

Practical solutions include improved human-factor training, stronger onboard leadership, and recognition that technology alone cannot eliminate risk. Just as songs once aligned human effort, modern systems must align human understanding.

Shipping companies, guided by frameworks from organizations such as the International Chamber of Shipping, increasingly integrate cultural awareness and crew wellbeing into operational policy.

Case Studies and Real-World Applications

Training and simulator environments

Maritime academies sometimes use historical context to explain why teamwork matters. When students understand how sailors once depended entirely on each other, modern concepts like BRM become more intuitive.

Crew cohesion on long voyages

Onboard traditions—shared meals, celebrations, informal rituals—continue the function once served by shanties. These practices help multinational crews build trust, improving safety and efficiency.

Future Outlook and Maritime Trends

The maritime industry is becoming more automated, but not less human. Autonomous systems may reduce workload, yet decision-making, ethics, and responsibility remain human concerns.

Cultural heritage, including sea shanties, will likely find a place in maritime storytelling, training, and outreach. As shipping seeks to attract new generations, connecting modern careers to rich traditions may prove essential.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What does “there once was a ship that put to sea” mean?

It introduces a traditional sea shanty, symbolizing the start of a voyage and life at sea.

Was the ship real?

The line is symbolic, representing many ships rather than a single vessel.

Why were sea shanties important?

They coordinated work, reduced fatigue, and strengthened crew cohesion.

Are shanties still used today?

Not operationally, but their principles survive in modern teamwork practices.

Why did the song become popular again?

Its simplicity, rhythm, and themes resonated globally, especially during isolation.

What can modern shipping learn from shanties?

That human coordination and morale are as vital as technology.

Conclusion

“There once was a ship that put to sea” is more than a lyric—it is a doorway into maritime history, culture, and human resilience. Behind the words lie centuries of labor, risk, and cooperation that shaped global trade long before engines and electronics.

For today’s maritime professionals and students, understanding this heritage enriches technical knowledge with human meaning. Ships still put to sea, crews still rely on each other, and the ocean remains indifferent. The tools have changed, but the essence of seafaring endures.

References

-

International Maritime Organization – https://www.imo.org

-

International Chamber of Shipping – https://www.ics-shipping.org

-

International Labour Organization – https://www.ilo.org

-

Marine Accident Investigation Branch – https://www.gov.uk/maib

-

Bowditch, N. The American Practical Navigator.

-

Calder, N. Boatowner’s Mechanical and Electrical Manual.