Nestled between the rugged southern coastline of Iran and the mountainous Musandam Peninsula of Oman, the Strait of Hormuz is far more than a narrow body of water. It is the single most important maritime chokepoint on Earth—an indispensable artery linking the oil- and gas-rich Persian Gulf to the Gulf of Oman and the wider Indian Ocean. At the same time, it is a complex marine ecosystem, a demanding navigational environment, and a persistent geopolitical flashpoint whose stability directly affects global energy markets, insurance rates, and maritime security.

This refined and expanded guide examines the Strait of Hormuz in its full physical, environmental, economic, and strategic dimensions—from seabed bathymetry and wind systems to biodiversity, shipping regimes, and its long record of maritime conflict.

Geographic Overview: The World’s Most Strategic Maritime Bottleneck

The Strait of Hormuz forms the only natural maritime gateway between the Persian Gulf and the open oceans. Stretching approximately 104 miles (167 km) in length, its width narrows dramatically—from around 60 miles (97 km) at its widest to just 24 miles (39 km) at its narrowest navigable point.

This constriction creates a classic chokepoint. On any given day, dozens of Very Large Crude Carriers (VLCCs), LNG carriers, product tankers, and container ships pass through a space where even minor disruptions can have global repercussions. Roughly one-fifth of the world’s seaborne oil trade and a significant share of liquefied natural gas exports transit this corridor, primarily from Gulf producers to markets in Asia, Europe, and North America.

Geographically, the strait is framed by arid coastlines, rocky headlands, and small islands—most notably Hormuz Island—whose strategic value has been recognized for centuries by regional powers and global empires alike.

Depth, Bathymetry, and Seabed Characteristics

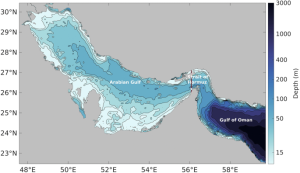

From a navigational perspective, the Strait of Hormuz is remarkably accommodating despite its narrowness. Water depths generally range between 200 and 330 feet (60–100 meters), with the deepest sections located closer to the Omani side near the Musandam Peninsula.

The Persian Gulf itself is a relatively shallow semi-enclosed basin, rarely exceeding 300 feet (90 meters) in depth. However, at its eastern entrance—precisely where it meets the Strait of Hormuz—depths increase beyond 360 feet (110 meters), creating a natural deep-water corridor suitable for ultra-large tankers.

The seabed is largely composed of sand, silt, and carbonate sediments, with limited submerged hazards. This bathymetric profile is one of the reasons the strait can support such intense and continuous heavy shipping traffic with relatively low grounding risk under normal operating conditions.

Climate, Rainfall, and Extreme Aridity

The Strait of Hormuz lies within one of the most arid climatic zones on the planet. Annual rainfall is extremely low, typically between 1 and 6 inches (35–150 mm), with precipitation concentrated in short winter episodes.

Rainfall events, though rare, can be visually striking. On Hormuz Island, for example, mineral-rich soils interact with runoff to produce vivid red-colored flows along the coast—a dramatic but short-lived phenomenon.

Air and sea temperatures are consistently high. Surface seawater temperatures usually range from 75 to 90 °F (24–32 °C), occasionally exceeding these values during peak summer months. High evaporation rates, combined with limited freshwater inflow from rivers, lead to elevated salinity levels—among the highest for any major sea connected to the global ocean system.

–

Wind Regimes, Currents, and Hydrodynamics

The physical environment of the strait is shaped by a combination of winds, tides, and density-driven circulation.

Wind Patterns

The dominant regional wind is the shamal, a north-northwesterly wind prevalent during summer months. While typically moderate, it can generate rough seas and reduced visibility due to dust and haze. In autumn, the region is occasionally affected by sudden convective storms, squalls, and even waterspouts, with localized wind speeds capable of increasing dramatically within minutes.

Tidal and Residual Currents

Tidal currents are strongest at the eastern entrance of the Persian Gulf, where speeds can reach up to 5 miles (8 km) per hour. Elsewhere within the strait, currents are generally weaker but can become complex and variable due to wind forcing and coastal geometry.

Density-Driven Exchange

A two-layer circulation system characterizes the strait. Less saline surface water flows inward from the Indian Ocean, while denser, highly saline Persian Gulf water exits beneath it. This exchange is critical for maintaining oxygen levels and overall water quality within the Gulf.

–

Navigation, Traffic Separation, and Legal Regimes

Given the extraordinary volume of traffic, navigation through the Strait of Hormuz is tightly regulated. A formal Traffic Separation Scheme (TSS) is in place, consisting of:

-

One inbound lane and one outbound lane

-

Each lane approximately two nautical miles wide

-

A two-mile separation zone between lanes

These routes pass through territorial waters of both Iran and Oman. Under international maritime law, vessels enjoy the right of transit passage, allowing continuous and expeditious navigation without interference. However, differing interpretations of security rights, environmental controls, and military presence have repeatedly generated tension and uncertainty for commercial operators.

For shipmasters, transit planning involves heightened watchkeeping, strict adherence to COLREGs, constant VHF monitoring, and close coordination with company security procedures.

–

A Surprisingly Rich Marine Ecosystem

Despite relentless shipping activity and extreme environmental conditions, the Strait of Hormuz supports a diverse marine ecosystem.

Coral reefs—though stressed—persist in pockets, providing habitat for reef fish and invertebrates. Larger pelagic species such as tuna, kingfish, and grouper are common, while dolphins and sea turtles regularly transit the area. Importantly, the strait serves as a migratory corridor for whale sharks moving between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman.

This ecological richness exists under constant pressure. Oil pollution, ballast-water discharge, underwater noise, coastal development, and the ever-present risk of conflict all threaten the long-term resilience of these ecosystems.

–

Strategic History and Maritime Conflict

The Strait of Hormuz has been contested for centuries, but its modern strategic significance crystallized with the rise of the global oil economy.

The Tanker War (1980–1988)

During the Iran–Iraq War, both sides targeted commercial shipping in what became known as the Tanker War. Hundreds of merchant vessels were attacked or damaged by missiles, mines, and aircraft. Several ships were sunk, and global energy markets were repeatedly shaken. The conflict prompted the intervention of international naval forces to escort and protect tankers.

Contemporary Tensions

In recent decades, the strait has remained a focal point of geopolitical friction. Incidents have included vessel seizures, drone and missile threats, and high-profile collisions and fires involving tankers. Each event reinforces the reality that even limited disruption in this narrow corridor can have outsized global consequences.

–

Economic and Energy Significance

Beyond crude oil, the Strait of Hormuz plays a critical role in the global movement of liquefied natural gas (LNG), refined petroleum products, petrochemicals, and a wide range of general and project cargoes. Major Gulf producers rely on this narrow passage not only to export crude oil, but also to supply LNG and refined fuels to international markets. Energy-importing economies—particularly in East Asia and South Asia, including countries such as China, Japan, South Korea, and India—are highly dependent on the uninterrupted flow of shipments through the strait. Any sustained restriction would force longer alternative routes, increase transport costs, and place immediate pressure on national energy security and electricity generation systems.

The economic influence of the Strait of Hormuz extends well beyond physical cargo flows. Marine insurance premiums, war-risk surcharges, freight rates, and charterparty clauses are all extremely sensitive to perceived security conditions in the area. Even short-lived incidents—such as vessel seizures, drone activity, or naval exercises—can trigger higher insurance costs, revised contractual terms, and delays in voyage planning. Political statements, changes in regional military posture, or isolated maritime accidents are often rapidly reflected in oil prices, shipping markets, and financial indices, demonstrating how closely global economic stability is tied to the safety and predictability of this strategic maritime corridor.

Regional and Global Economic Consequences of Instability

Instability in the Strait of Hormuz would have immediate and serious consequences for Arab countries of the Persian Gulf, whose economies depend heavily on uninterrupted oil, gas, and petrochemical exports. Any disruption to shipping would reduce export volumes, delay deliveries, and increase transport and insurance costs, placing direct pressure on government revenues, public spending, and long-term economic planning. Even short periods of heightened risk can undermine investor confidence and increase economic volatility across the region.

Beyond energy exports, instability would weaken the wider trade and logistics ecosystem of Gulf states. Higher war-risk premiums and freight rates would raise the cost of both exports and imports, reduce port competitiveness, and divert cargo to alternative routes. This would affect refineries, industrial zones, and regional logistics hubs that rely on predictable maritime flows.

At the international level, disruptions in the Strait of Hormuz would strain trade and energy contracts with major partners such as the United States, the European Union, and China. Supply interruptions could trigger contract renegotiations, force majeure claims, and price volatility, affecting both exporters and importers. Over time, sustained instability could accelerate supply diversification, reshape energy trade relationships, and alter long-term geopolitical and economic alignments between Gulf Arab states and their key global partners.

–

Conclusion: A Narrow Passage with Global Consequences

The Strait of Hormuz is a place where geography exerts disproportionate influence over global affairs. Its depth and width shape tanker design and routing strategies; its winds and currents test seamanship; its ecosystems persist under extraordinary stress; and its political volatility commands constant international attention.

As the primary maritime gateway for a substantial share of the world’s energy supply, the stability of this narrow waterway is not merely a regional issue—it is a matter of global economic security. A comprehensive understanding of the Strait of Hormuz, encompassing its physical characteristics, environmental value, navigational complexity, and turbulent history, is essential for grasping how modern maritime trade and geopolitics are intertwined.