The Persian Gulf is a shallow, semi-enclosed sea in West Asia, lying between Iran to the north and the Arabian Peninsula to the south and west. It connects to the wider ocean system through the Strait of Hormuz, which opens into the Gulf of Oman and then to the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean.

For the maritime sector, the Persian Gulf is one of the most operationally important seas on Earth. It supports some of the world’s densest concentrations of oil and gas terminals, offshore production platforms, tanker traffic, and industrial coastal infrastructure. At the same time, it is an environmentally sensitive basin where shallow depths, high evaporation, and limited water exchange can intensify ecological stress. This combination—high commercial value plus high environmental sensitivity—makes the Persian Gulf a “high-consequence” maritime environment. Small events can become big, fast.

The Persian Gulf’s story is also deeply human. Coastal communities have depended on its waters for millennia through fishing, pearling, coastal trade, and navigation. Today, that same sea is central to global energy security, regional development, and international shipping risk management.

Geography

Location and boundaries

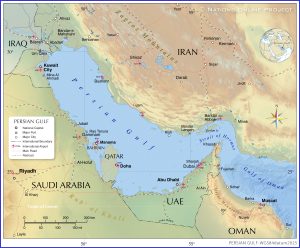

The Persian Gulf is commonly described as an inland sea connected to the Indian Ocean system via the Strait of Hormuz. Its southwestern and southern shores border the Arabian Peninsula, while the northern shore follows Iran’s coastline. In the northwest, the sea meets the low-lying deltaic coast formed by the Shatt al-Arab river system, which carries water from the Tigris and Euphrates.

From a navigation and hydrography standpoint, the Persian Gulf behaves like a basin with a single “doorway” (Hormuz). That single exit route shapes shipping patterns, port development, and maritime security planning. When a sea has only one main outlet, the entire traffic system becomes naturally concentrated—like a highway that narrows into one toll gate.

Size, depth, and navigational character

The Persian Gulf is large in surface area but shallow in depth. Many areas are relatively flat and gently sloping. This matters to ship operators because shallow seas change how vessels behave and how risks accumulate.

In shallow water, a ship can experience:

-

Squat (the vessel sits lower in the water at speed)

-

Reduced maneuverability (especially for large tankers)

-

Higher sensitivity to under-keel clearance planning

-

Greater consequences from groundings because recovery options may be limited and environmental impacts can be severe

Shallow water also influences how waves build and how sediment moves. After storms, some nearshore approaches may experience shifting sandbanks or altered seabed profiles, which reinforces the importance of up-to-date hydrographic surveying and careful pilotage.

Coastlines and basin states

Eight states have coastlines on the Persian Gulf: Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, and Oman (via the Musandam exclave).

Each coastline has developed in a different way, but the overall pattern is similar across the region: ports, industrial zones, energy infrastructure, and coastal cities cluster near navigable waters and sheltered approaches. Over time, this has created a highly “engineered” shoreline in many areas, with extensive dredging, land reclamation, breakwaters, causeways, and artificial harbors.

For mariners, this means the Persian Gulf is not just a natural sea—it is also a constructed maritime operating system, where many navigational routes pass close to infrastructure, exclusion zones, and high-value assets.

Maritime routes and the Strait of Hormuz effect

Because the Strait of Hormuz connects the Persian Gulf to the open ocean, it functions as a route-shaping gateway. Tankers, LNG carriers, container ships serving regional hubs, offshore support vessels, naval units, and fishing craft all share the same general corridor system, often under traffic separation arrangements and local routing practices.

This concentration produces a distinctive risk profile:

-

High traffic density

-

Mixed vessel types and speeds

-

Complex watchkeeping conditions (especially at night or in reduced visibility)

-

Strong incentive for schedule discipline, which can increase operational pressure

In practical terms, seamanship in the Persian Gulf is often less about “blue water navigation” and more about traffic management, situational awareness, and disciplined bridge team routines.

Islands

The Persian Gulf contains many islands of different sizes and functions. Some are natural islands with long histories of settlement and trade; others are strategic outposts or modern developments tied to tourism and real estate.

Large and well-known islands include Qeshm (near the Strait of Hormuz) and Kish. Bahrain is itself an island state, historically linked to pearling and maritime commerce.

Islands matter in maritime operations because they shape:

-

Traffic corridors and route geometry

-

Pilot boarding and anchorage patterns

-

Placement of navigation aids and radar marks

-

Local current behavior around headlands and narrow channels

In addition, islands can influence territorial and jurisdictional boundaries, which affects enforcement, security coordination, and sometimes operational reporting requirements. Even when ships follow international best practice, they may pass through waters with different regulatory expectations within short time spans.

Oceanography

Water exchange and salinity structure

The Persian Gulf experiences strong evaporation and limited freshwater input compared with many other seas. This helps explain why Gulf waters tend to be relatively saline. Water exchange through the Strait of Hormuz supports balance, often described as a two-layer flow pattern: less saline ocean water enters near the surface, while denser, saltier Persian Gulf water flows out at depth.

For maritime learners, the key idea is simple: the Persian Gulf is like a shallow basin under strong “solar heating.” Water does not circulate as freely as the open ocean, so the sea’s chemistry and temperature can become extreme.

Temperature stress and seasonal variability

The Persian Gulf is known for high summer sea surface temperatures. Seasonal changes can be sharp, and shallow areas can warm quickly. These conditions stress corals and other temperature-sensitive species, and they also affect maritime operations in subtle ways—such as crew fatigue, equipment cooling demands, and the performance of some onboard systems.

Sediment, turbidity, and coastal engineering impacts

Sediment carried by river systems in the northwest and disturbed by dredging and reclamation in some coastal zones can affect water clarity. Turbidity matters ecologically (because corals require light) and operationally (because poor visibility can influence small craft navigation and certain nearshore activities).

Coastal engineering can also change local wave patterns and currents. Over time, large breakwaters and artificial islands may shift sediment deposition zones, which can create maintenance dredging needs and long-term shoreline change.

Name

Historical continuity and modern usage

The name Persian Gulf has long historical roots in geography, cartography, and scholarly writing. In international maritime education and navigation, consistency in naming supports safe communication, chart interpretation, and training standardization.

Naming sensitivity and professional communication

The Persian Gulf is sometimes at the center of political and cultural sensitivities regarding naming conventions. In professional maritime settings, the best practice is to use clear, consistent terminology, aligned with charting standards and institutional references, so that navigation, reporting, and training materials remain unambiguous.

In this article, the term Persian Gulf is used consistently to support clarity and standardization for learners and mariners.

History

Ancient history

Human presence around the Persian Gulf goes back thousands of years. The Gulf’s shallow coastal waters offered fish, shellfish, and navigable routes for early trade. Long before modern ports and tankers, coastal craft connected settlements through short sea passages—an early form of maritime network economy.

One of the most important historical roles of the Persian Gulf was as a connector between Mesopotamia, the Iranian plateau, and the Arabian Peninsula. Goods, people, and ideas moved along coasts and between islands. Maritime trade was not a side activity; it was a core mechanism of regional development.

Pearling also became a defining historical industry for some coastal communities, shaping social structures and seasonal labor patterns. Even today, cultural memory of pearling remains significant in parts of the region, and it helps explain why maritime identity runs deep along the Gulf coast.

Empires, trade control, and early sea power

Over centuries, states and empires sought influence over ports and island positions because controlling maritime nodes meant controlling commerce. Coastal towns acted as entry points for taxation and trade regulation, while ship patrols and naval bases protected routes and enforced authority.

A key maritime lesson from this period is that “sea control” is rarely only a naval concept. It also includes:

-

control of harbor access

-

provisioning and repair capability

-

jurisdictional enforcement

-

the ability to maintain predictable trade conditions

These elements still define modern port strategy and maritime security.

Colonial era

European maritime expansion into the Indian Ocean brought the Persian Gulf into wider geopolitical competition. Fortified positions and alliances emerged around strategic islands and coastal towns, especially near chokepoints linked to Hormuz.

Over time, external influence interacted with local power structures, producing treaties and maritime campaigns intended to reduce piracy and stabilize trade flows. Maritime security measures were often motivated by commercial reliability: merchants and shipowners wanted predictable routes, safe anchorages, and enforceable rules.

The longer-term impact of this era can still be seen in some administrative boundaries, port development patterns, and institutional legacies in maritime governance.

Modern history

In the late 20th century and early 21st century, the Persian Gulf became closely associated with global energy trade and security risk. Conflicts in the region revealed how quickly commercial shipping can be pulled into strategic pressure.

From a shipping industry perspective, modern Gulf risk management often involves:

-

route planning with security advisories in mind

-

war-risk and additional premium considerations

-

strengthened watchkeeping and reporting routines

-

port and terminal security compliance under the ISPS framework

-

coordination with flag state guidance and company security officers

Even when voyages remain uninterrupted, the perception of risk can affect freight rates, charterparty clauses, scheduling choices, and crew welfare considerations.

Cities and population

The Persian Gulf coastline includes some of the Middle East’s most prominent cities and industrial zones. Coastal development has been driven by a mix of port growth, offshore energy activity, logistics expansion, and urbanization.

Major coastal cities function as:

-

port hubs for containerized and general cargo

-

energy export and refining centers

-

service bases for offshore support vessels

-

maritime labor and training nodes

-

trade and finance centers linked to shipping and logistics

For maritime learners, it helps to visualize the Persian Gulf coastline as a network of interconnected operational nodes. A single tanker voyage may involve offshore loading, pilotage, anchorage management, customs coordination, and strict terminal schedules—all within a compact geographic area.

Wildlife

The Persian Gulf supports diverse marine life, but its ecological resilience is challenged by shallow-sea stress, high temperatures, coastal construction, industrialization, and pollution exposure.

A useful way to understand the ecosystem is to think of it as a shallow, highly productive coastal nursery operating under harsh conditions. When habitats remain intact, the system supports impressive biodiversity. When habitats are damaged, the impacts can spread quickly because many species depend on the same shallow zones for feeding and breeding.

Aquatic mammals

Dolphins and porpoises are among the most frequently observed marine mammals. Dugongs are especially important ecologically and culturally, as they depend on healthy seagrass meadows. When seagrass is degraded—by turbidity, dredging, coastal alteration, or pollution—dugongs lose feeding grounds and may struggle to maintain population stability.

Marine mammals in the Persian Gulf face risks that are common in busy coastal seas:

-

vessel strikes in high-traffic corridors

-

entanglement in fishing gear

-

habitat disturbance near construction and dredging sites

-

exposure to chronic pollution (oil residues, sewage discharge, industrial runoff)

Birds

The Persian Gulf lies along migratory pathways and contains critical resting and nesting habitats, including mudflats, wetlands, and mangroves. Many coastal birds depend on shallow intertidal zones where they feed on small fish and invertebrates.

When coastlines are heavily modified—through reclamation, seawalls, channels, or artificial islands—intertidal habitat may shrink. This can reduce feeding areas and increase competition among birds during migration seasons.

Fish and reefs

The Persian Gulf supports hundreds of fish species, many associated with reef and structured habitats. Coral communities exist but are vulnerable due to thermal stress, variable salinity, and water quality pressures.

When reef systems decline, the impact is not limited to corals themselves. Reefs act like underwater cities: they provide shelter, breeding space, and feeding opportunities. If reefs degrade, fish abundance and diversity can fall, which then affects artisanal fishing and overall food-web stability.

Flora (including mangroves)

Mangroves are among the most valuable coastal habitats in the Persian Gulf. They stabilize shorelines, trap sediment, and provide nursery areas for juvenile fish and crustaceans. They also support bird populations and improve nearshore water quality.

Because mangroves grow in shallow coastal areas, they are especially exposed to land reclamation and shoreline construction. Protecting mangroves is not only an environmental policy choice—it is also a practical coastal resilience strategy.

Oil and gas

The Persian Gulf is one of the world’s most important maritime energy centers. Offshore oilfields, gas fields, subsea pipelines, export terminals, and large refining complexes form a dense industrial system connected by shipping lanes.

Offshore production and export logistics

Offshore infrastructure includes fixed platforms, floating installations, subsea wellheads, and extensive pipeline networks. These facilities depend on reliable offshore support operations—platform supply vessels, tugs, crew boats, and specialized maintenance vessels.

Export logistics rely heavily on:

-

tanker loading terminals and offshore moorings

-

scheduling systems aligned with production and storage constraints

-

stringent safety management due to hazardous cargo

-

emergency response capability and spill preparedness

North Field / South Pars and the LNG supply chain

One of the world’s largest shared gas reservoirs underpins major LNG production and export capacity in the region. LNG operations require specialized ports and highly controlled terminal procedures, because LNG cargo management is safety-critical and technologically demanding.

For maritime professionals, LNG logistics is a high-discipline domain: cargo systems, emergency shutdown procedures, exclusion zones, and compatibility checks are central features of every port call.

The Strait of Hormuz as a global energy gateway

The Strait of Hormuz is the Persian Gulf’s maritime gateway and a central node in global energy supply chains. Because the Persian Gulf’s export system is geographically concentrated, the Strait of Hormuz has a global influence on freight markets, insurance pricing, and energy trade continuity.

When the operating environment becomes uncertain, shipping does not always stop—but it becomes more expensive and more complex. Companies may adopt conservative routing, increase security measures, adjust schedules, and renegotiate charterparty risk clauses.

Environmental and safety governance in a high-density sea

Energy shipping and offshore production increase environmental stakes. In a shallow basin, pollution events can be harder to dilute and can affect coastlines quickly. That is why maritime environmental compliance in the Persian Gulf is operationally meaningful, not theoretical.

Key maritime governance frameworks relevant to operations include:

-

MARPOL controls on discharges and pollution prevention

-

SOLAS safety requirements affecting shipboard systems and emergency readiness

-

ISPS Code security requirements for ships and port facilities

-

port state control practices and inspection regimes

References

(End reference list only; no in-text citations were used.)

-

International Hydrographic Organization. (1953). Limits of Oceans and Seas (Special Publication No. 23), 3rd ed. https://epic.awi.de/29772/1/IHO1953a.pdf

-

U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2025). Today in Energy: Strait of Hormuz flows and global trade shares (2024–1Q 2025). https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=65504

-

ROPME. (2022). Climate change risk assessment policy brief for the ROPME Sea Area. https://ropme.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Risk-Assessment-Policy-Brief-English.pdf

-

International Maritime Organization (IMO). Official website and conventions (SOLAS, MARPOL, ISPS). https://www.imo.org

-

International Chamber of Shipping (ICS). Shipping policy and industry guidance. https://www.ics-shipping.org

-

International Association of Classification Societies (IACS). Classification and technical standards. https://iacs.org.uk

-

American Bureau of Shipping (ABS). Rules, class and advisory resources. https://www.eagle.org

-

DNV. Maritime research and risk/assurance resources. https://www.dnv.com

-

Lloyd’s Register. Maritime safety and class resources. https://www.lr.org

-

World Bank. Trade and logistics resources. https://www.worldbank.org