Access to the Sea and the Challenges of Landlocked Nations

Throughout history, access to the sea has been one of the most important determinants of a nation’s economic trajectory. Coastal states have traditionally flourished because seaports serve as gateways to international markets, allowing goods, ideas, and people to circulate more freely. By contrast, landlocked countries—those without direct access to the ocean—have faced enduring disadvantages. Their trade routes are longer and more expensive, their economies more dependent on neighbors, and their integration into global supply chains slower and less complete.

The Core Challenges of Being Landlocked

The most immediate challenge is the lack of direct maritime trade. Since nearly 80 percent of global trade by volume is transported by sea (UNCTAD), countries without a coastline must rely on transit through neighboring states to import and export goods. This dependence creates layers of vulnerability: delays at borders, exposure to political disputes, and additional customs procedures all add cost and uncertainty.

Transport costs are significantly higher as a result. Goods leaving a landlocked nation typically move first by road or rail to a coastal port, often passing through multiple jurisdictions before they even reach the ship. According to the World Bank, landlocked developing countries can pay up to 50 percent more in transport costs compared to their coastal counterparts. These higher costs erode competitiveness, making it more difficult for domestic industries to export and for consumers to access affordable imports.

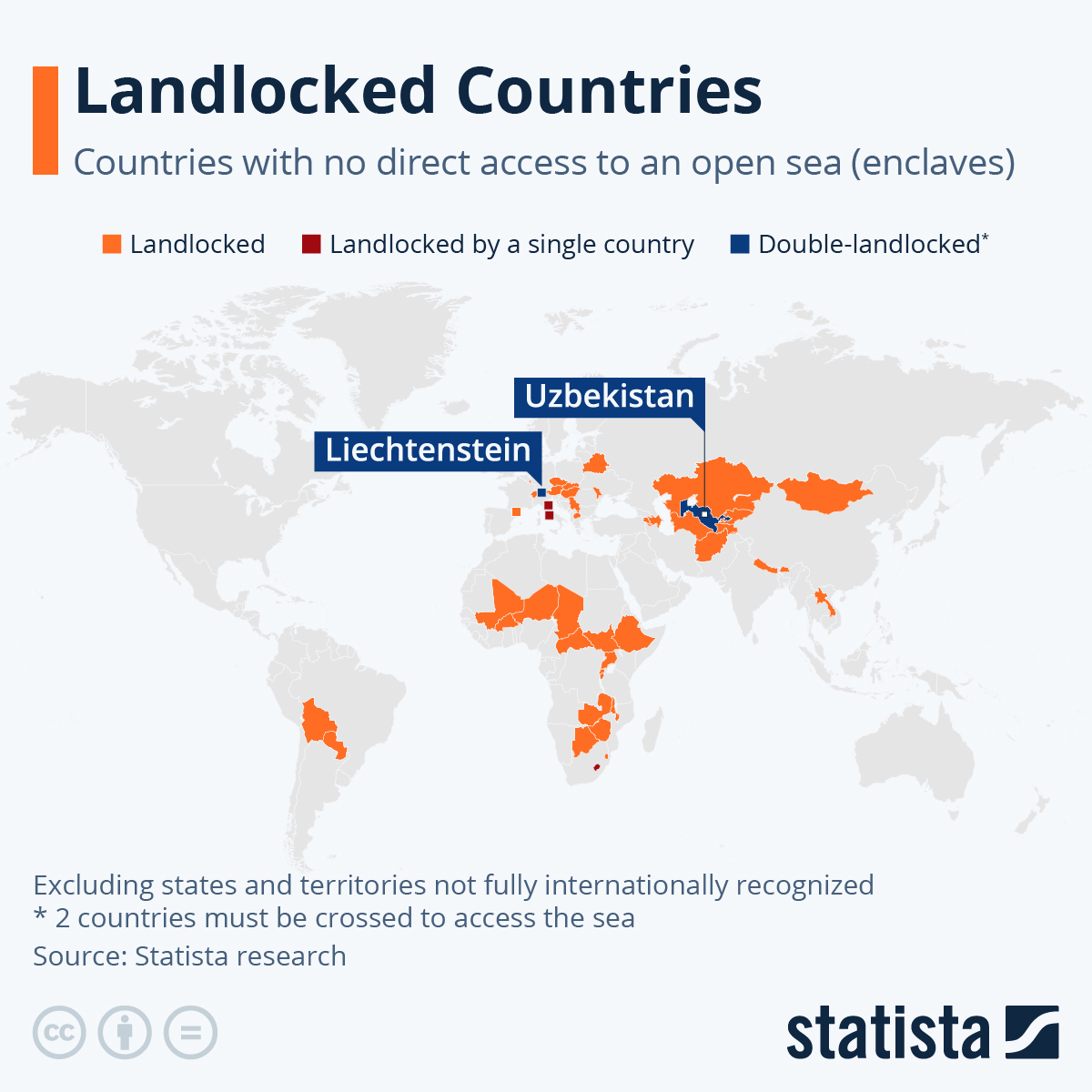

Beyond trade, landlocked states also miss out on direct access to fisheries, offshore energy, and other marine resources, which for many coastal nations provide substantial income and food security. The absence of these industries further narrows economic opportunities. Not surprisingly, of the world’s 44 landlocked nations, 32 are classified as developing countries, and many struggle to achieve sustained growth.

The Extreme Case: Double-Landlocked Countries

The challenge is even more acute for the world’s two double-landlocked countries, which must cross two international borders before reaching the sea.

-

Liechtenstein, a small European principality, is encircled by Switzerland and Austria. While its economy is stable and prosperous thanks to financial services and close integration with the EU, its geography underscores the reliance on cooperative neighbors.

-

Uzbekistan, in Central Asia, faces a far tougher situation. Surrounded by five other landlocked states—Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan—Uzbekistan is heavily dependent on long overland corridors to access ports in the Caspian Sea, the Black Sea, or even China. This extreme isolation makes trade slower and more expensive, limiting its ability to compete in global markets.

For both countries, but especially for Uzbekistan, being double-landlocked magnifies the geopolitical stakes of regional cooperation. Any disruption in neighboring states—be it political instability, conflict, or infrastructure failure—can ripple outward and severely constrain trade.

Why Maritime Access Matters

The importance of maritime access becomes clear when looking at global economic rankings. Coastal nations dominate the list of the world’s largest economies, partly because of their ability to integrate efficiently into global trade networks. Ports like Shanghai, Singapore, Rotterdam, and Los Angeles act as economic multipliers, generating billions in trade-related services and industries.

Landlocked nations, meanwhile, must rely heavily on regional logistics agreements and corridors. The difference in cost and efficiency is stark. A container moving from a coastal port to an inland city may travel seamlessly within a single jurisdiction, but for a landlocked country, the same container often requires multiple transfers, additional documentation, and longer transit times. These inefficiencies accumulate, reducing competitiveness and discouraging foreign investment.

The absence of maritime access also has strategic implications. Nations with coastlines can project influence through naval power, protect sea lanes, and participate directly in global maritime governance. Landlocked countries, on the other hand, are more limited in their geopolitical reach and must rely on diplomatic arrangements with maritime neighbors.

Can Landlocked Countries Overcome the Disadvantage?

Despite these challenges, many landlocked states have pursued creative strategies to reduce their geographic disadvantage. Trade agreements with coastal neighbors are crucial. For example, Botswana relies on South Africa’s port of Durban to connect with global markets, while Nepal depends on Indian ports for most of its imports and exports. Without these agreements, trade would be prohibitively expensive.

Infrastructure investment is equally important. Kazakhstan’s participation in China’s Belt and Road Initiative has created extensive rail and road corridors linking Central Asia to ports in the Pacific and Europe. These connections are reshaping its role as a land bridge rather than a landlocked backwater, though dependency on external financing raises questions of sovereignty and long-term sustainability.

Regional economic blocs have also helped reduce barriers. The East African Community (EAC), for example, enables Uganda and Rwanda to use Kenyan and Tanzanian ports under preferential trade terms, streamlining customs procedures and lowering costs. Such cooperation demonstrates that while geography is a constraint, regional diplomacy can partially overcome it.

Still, the structural disadvantage remains significant, especially in Africa, where 16 countries are landlocked. For many of these nations, dependence on sometimes unstable neighbors makes trade corridors fragile, limiting their ability to fully participate in global commerce. Until alternative infrastructure such as dry ports, high-speed rail corridors, and integrated customs systems become widespread, landlocked countries will continue to face steep economic hurdles.

Geography as Destiny—But Not Permanently

History has shown that geography exerts powerful influence on a nation’s fortunes. Coastal access has been synonymous with prosperity, while isolation inland has slowed development. Yet, while geography cannot be changed, its impact can be mitigated through policy, infrastructure, and cooperation.

Landlocked nations that invest strategically in connectivity, regional partnerships, and diversified trade routes can overcome some of these disadvantages. However, the disparity between coastal and landlocked countries remains one of the most persistent and visible reminders of how geography continues to shape the global economic order.