The International Maritime Organization – is the United Nations specialized agency with responsibility for the safety and security of shipping and the prevention of marine and atmospheric pollution by ships. IMO’s work supports the UN sustainable development goals.

As a specialized agency of the United Nations, IMO is the global standard-setting authority for the safety, security and environmental performance of international shipping. Its main role is to create a regulatory framework for the shipping industry that is fair and effective, universally adopted and universally implemented. In other words, its role is to create a level playing-field so that ship operators cannot address their financial issues by simply cutting corners and compromising on safety, security and environmental performance. This approach also encourages innovation and efficiency.

Shipping is a truly international industry, and it can only operate effectively if the regulations and standards are themselves agreed upon, adopted and implemented internationally. And IMO is the forum at which this process takes place. International shipping transports more than 80 per cent of global trade to people and communities worldwide. Shipping is the most efficient and cost-effective method of international transportation for most goods; it provides a dependable, low-cost means of transporting goods globally, facilitating commerce and helping to create prosperity among nations and peoples.

The world relies on a safe, secure and efficient international shipping industry – and this is provided by the regulatory framework developed and maintained by IMO. IMO measures cover all aspects of international shipping – including ship design, construction, equipment, manning, operation and disposal – to ensure that this vital sector remains safe, environmentally sound, energy-efficient and secure. Shipping is an essential component of any programme for future sustainable economic growth. Through IMO, the Organization’s Member States, civil society and the shipping industry are already working together to ensure a continued and strengthened contribution towards a green economy and growth in a sustainable manner. The promotion of sustainable shipping and sustainable maritime development is one of the major priorities of IMO in the coming years.

List of IMO Conventions

Key IMO Conventions

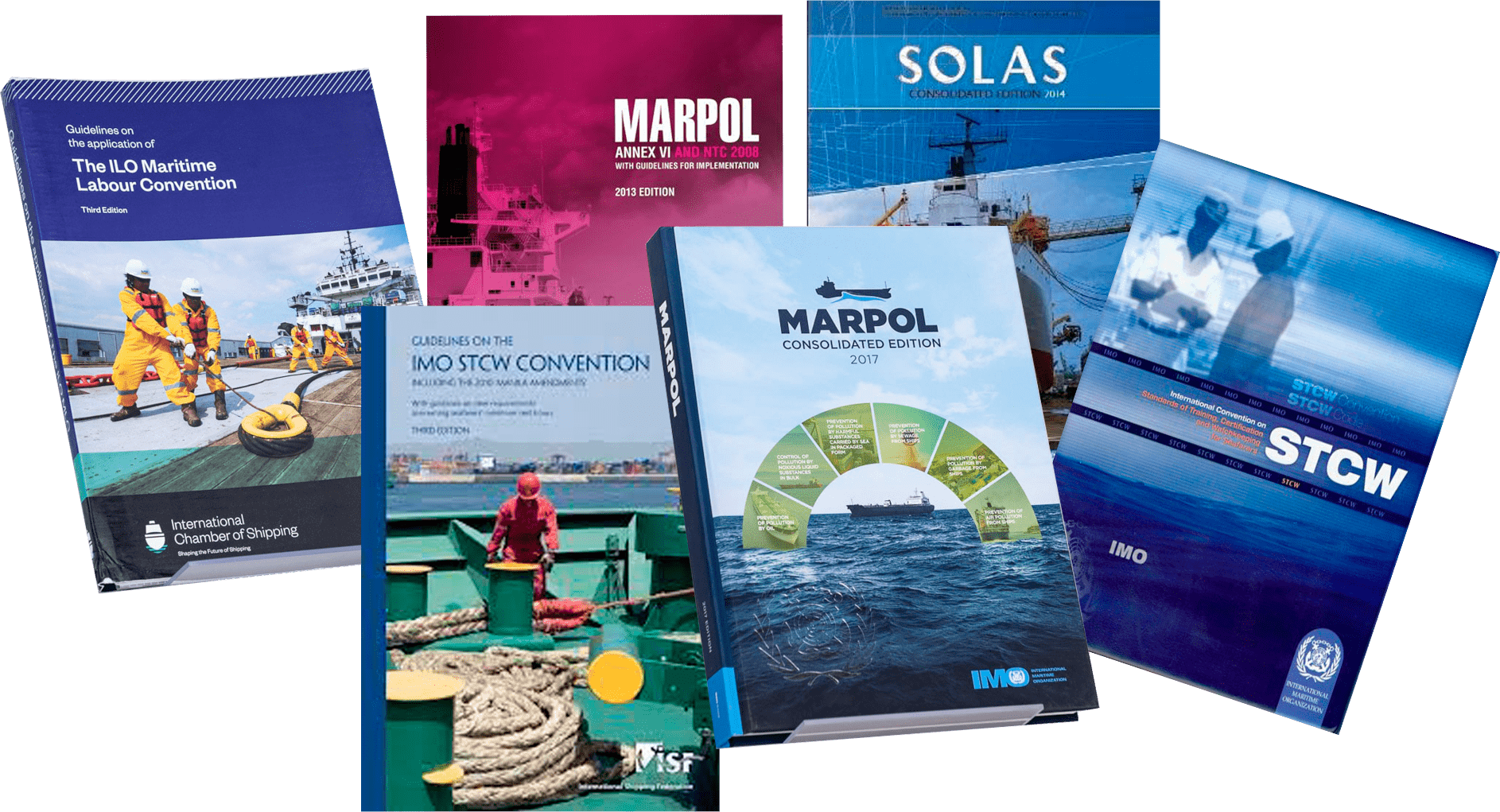

- International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), 1974, as amended,

- International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) 1973, as modified by the Protocol of 1978 relating thereto and by the Protocol of 1997,

- International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers ( STCW) as amended, including the 1995 and 2010 Manila Amendments.

Other conventions relating to maritime safety and security and ship/port interface

- Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREG), 1972

- Convention on Facilitation of International Maritime Traffic (FAL), 1965

- International Convention on Load Lines(LL), 1966

- International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue(SAR), 1979

- Convention for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts Against the Safety of Maritime Navigation(SUA), 1988, and Protocol for the Suppression of Unlawful Acts Against the Safety of Fixed Platforms located on the Continental Shelf (and the 2005 Protocols)

- International Convention for Safe Containers (CSC), 1972

- Convention on the International Maritime Satellite Organization (IMSO C), 1976

- The Torremolinos International Convention for the Safety of Fishing Vessels (SFV), 1977, superseded by the The 1993 Torremolinos Protocol; Cape Town Agreement of 2012 on the Implementation of the Provisions of the 1993 Protocol relating to the Torremolinos International Convention for the Safety of Fishing Vessels

- International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Fishing Vessel Personnel (STCW-F), 1995

- Special Trade Passenger Ships Agreement (STP), 1971 and Protocol on Space Requirements for Special Trade Passenger Ships, 1973

Other conventions relating to prevention of marine pollution

- International Convention Relating to Intervention on the High Seas in Cases of Oil Pollution Casualties (INTERVENTION), 1969

- Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter(LC), 1972 (and the 1996 London Protocol)

- International Convention on Oil Pollution Preparedness, Response and Co-operation(OPRC), 1990

- Protocol on Preparedness, Response and Co-operation to pollution Incidents by Hazardous and Noxious Substances, 2000 (OPRC-HNS Protocol)

- International Convention on the Control of Harmful Anti-fouling Systems on Ships (AFS), 2001

- International Convention for the Control and Management of Ships’ Ballast Water and Sediments, 2004

- The Hong Kong International Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships, 2009

Conventions covering liability and compensation

- International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage(CLC), 1969

- 1992 Protocol to the International Convention on the Establishment of an International Fund for Compensation for Oil Pollution Damage (FUND 1992)

- Convention relating to Civil Liability in the Field of Maritime Carriage of Nuclear Material (NUCLEAR), 1971

- Athens Convention relating to the Carriage of Passengers and their Luggage by Sea (PAL), 1974

- Convention on Limitation of Liability for Maritime Claims(LLMC), 1976

- International Convention on Liability and Compensation for Damage in Connection with the Carriage of Hazardous and Noxious Substances by Sea (HNS), 1996 (and its 2010 Protocol)

- International Convention on Civil Liability for Bunker Oil Pollution Damage, 2001

- Nairobi International Convention on the Removal of Wrecks, 2007

Other subjects

- International Convention on Tonnage Measurement of Ships (TONNAGE), 1969

- International Convention on Salvage (SALVAGE), 1989

Conventions

Adopting a convention, Entry into force, Accession, Amendment, Enforcement, Tacit acceptance procedure.

Introduction

The industrial revolution of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and the upsurge in international commerce which followed resulted in the adoption of a number of international treaties related to shipping, including safety. The subjects covered included tonnage measurement, the prevention of collisions, signalling and others. By the end of the nineteenth century suggestions had even been made for the creation of a permanent international maritime body to deal with these and future measures. The plan was not put into effect, but international co-operation continued in the twentieth century, with the adoption of still more internationally-developed treaties. By the time IMO came into existence in 1958, several important international conventions had already been developed, including the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea of 1948, the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution of the Sea by Oil of 1954 and treaties dealing with load lines and the prevention of collisions at sea. IMO was made responsible for ensuring that the majority of these conventions were kept up to date. It was also given the task of developing new conventions as and when the need arose. The creation of IMO coincided with a period of tremendous change in world shipping and the Organization was kept busy from the start developing new conventions and ensuring that existing instruments kept pace with changes in shipping technology. It is now responsible for more than 50 international conventions and agreements and has adopted numerous protocols and amendments.

Adopting a convention

This is the part of the process with which IMO as an Organization is most closely involved. IMO has six main bodies concerned with the adoption or implementation of conventions. The Assembly and Council are the main organs, and the committees involved are the Maritime Safety Committee, Marine Environment Protection Committee, Legal Committee and the Facilitation Committee. Developments in shipping and other related industries are discussed by Member States in these bodies, and the need for a new convention or amendments to existing conventions can be raised in any of them.

Entry into force

The adoption of a convention marks the conclusion of only the first stage of a long process. Before the convention comes into force – that is, before it becomes binding upon Governments which have ratified it – it has to be accepted formally by individual Governments.

Signature, ratification, acceptance, approval and accession

The terms signature, ratification, acceptance, approval and accession refer to some of the methods by which a State can express its consent to be bound by a treaty.

Signature

Consent may be expressed by signature where:

- the treaty provides that signature shall have that effect

- it is otherwise established that the negotiating States were agreed that signature should have that effect

- the intention of the State to give that effect to signature appears from the full powers of its representatives or was expressed during the negotiations (Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969, Article 12.1).

A State may also sign a treaty “subject to ratification, acceptance or approval”. In such a situation, signature does not signify the consent of a State to be bound by the treaty, although it does oblige the State to refrain from acts which would defeat the object and purpose of the treaty until such time as it has made its intention clear not to become a party to the treaty (Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, Article 18(a)).

Signature subject to ratification, acceptance or approval

Most multilateral treaties contain a clause providing that a State may express its consent to be bound by the instrument by signature subject to ratification.

In such a situation, signature alone will not suffice to bind the State, but must be followed up by the deposit of an instrument of ratification with the depositary of the treaty. This option of expressing consent to be bound by signature subject to ratification, acceptance or approval originated in an era when international communications were not instantaneous, as they are today.

It was a means of ensuring that a State representative did not exceed their powers or instructions with regard to the making of a particular treaty. The words “acceptance” and “approval” basically mean the same as ratification, but they are less formal and non-technical and might be preferred by some States which might have constitutional difficulties with the term ratification. Many States nowadays choose this option, especially in relation to multinational treaties, as it provides them with an opportunity to ensure that any necessary legislation is enacted and other constitutional requirements fulfilled before entering into treaty commitments.

The terms for consent to be expressed by signature subject to acceptance or approval are very similar to ratification in their effect. This is borne out by Article 14.2 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties which provides that “the consent of a State to be bound by a treaty is expressed by acceptance or approval under conditions similar to those which apply to ratification.”

Accession

Most multinational treaties are open for signature for a specified period of time. Accession is the method used by a State to become a party to a treaty which it did not sign whilst the treaty was open for signature.

Technically, accession requires the State in question to deposit an instrument of accession with the depositary. Article 15 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties provides that consent by accession is possible where the treaty so provides, or where it is otherwise established that the negotiating States were agreed or subsequently agreed that consent by accession could occur.

Amendment

Technology and techniques in the shipping industry change very rapidly these days. As a result, not only are new conventions required but existing ones need to be kept up to date. For example, the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), 1960 was amended six times after it entered into force in 1965 – in 1966, 1967, 1968, 1969, 1971 and 1973. In 1974 a completely new convention was adopted incorporating all these amendments (and other minor changes) and has been modified numerous times.

In early conventions, amendments came into force only after a percentage of Contracting States, usually two thirds, had accepted them. This normally meant that more acceptances were required to amend a convention than were originally required to bring it into force in the first place, especially where the number of States which are Parties to a convention is very large. This percentage requirement in practice led to long delays in bringing amendments into force. To remedy the situation a new amendment procedure was devised in IMO. This procedure has been used in the case of conventions such as the Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, 1972, the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 1973 and SOLAS 1974, all of which incorporate a procedure involving the “tacit acceptance” of amendments by States. Instead of requiring that an amendment shall enter into force after being accepted by, for example, two thirds of the Parties, the “tacit acceptance” procedure provides that an amendment shall enter into force at a particular time unless before that date, objections to the amendment are received from a specified number of Parties.

In the case of the 1974 SOLAS Convention, an amendment to most of the Annexes (which constitute the technical parts of the Convention) is `deemed to have been accepted at the end of two years from the date on which it is communicated to Contracting Governments…’ unless the amendment is objected to by more than one third of Contracting Governments, or Contracting Governments owning not less than 50 per cent of the world’s gross merchant tonnage. The Maritime Safety Committee may vary this period with a minimum limit of one year. As was expected the “tacit acceptance” procedure has greatly speeded up the amendment process. Amendments enter into force within 18 to 24 months, generally Compared to this, none of the amendments adopted to the 1960 SOLAS Convention between 1966 and 1973 received sufficient acceptances to satisfy the requirements for entry into force.

Enforcement

The enforcement of IMO conventions depends upon the Governments of Member Parties.

Contracting Governments enforce the provisions of IMO conventions as far as their own ships are concerned and also set the penalties for infringements, where these are applicable. They may also have certain limited powers in respect of the ships of other Governments.

In some conventions, certificates are required to be carried on board ship to show that they have been inspected and have met the required standards. These certificates are normally accepted as proof by authorities from other States that the vessel concerned has reached the required standard, but in some cases further action can be taken. The 1974 SOLAS Convention, for example, states that “the officer carrying out the control shall take such steps as will ensure that the ship shall not sail until it can proceed to sea without danger to the passengers or the crew”. This can be done if “there are clear grounds for believing that the condition of the ship and its equipment does not correspond substantially with the particulars of that certificate”. An inspection of this nature would, of course, take place within the jurisdiction of the port State. But when an offence occurs in international waters the responsibility for imposing a penalty rests with the flag State.

Should an offence occur within the jurisdiction of another State, however, that State can either cause proceedings to be taken in accordance with its own law or give details of the offence to the flag State so that the latter can take appropriate action. Under the terms of the 1969 Convention Relating to Intervention on the High Seas, Contracting States are empowered to act against ships of other countries which have been involved in an accident or have been damaged on the high seas if there is a grave risk of oil pollution occurring as a result.

The way in which these powers may be used are very carefully defined, and in most conventions the flag State is primarily responsible for enforcing conventions as far as its own ships and their personnel are concerned. The Organization itself has no powers to enforce conventions. However, IMO has been given the authority to vet the training, examination and certification procedures of Contracting Parties to the International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers (STCW), 1978. This was one of the most important changes made in the 1995 amendments to the Convention which entered into force on 1 February 1997. Governments have to provide relevant information to IMO’s Maritime Safety Committee which will judge whether or not the country concerned meets the requirements of the Convention.

Relationship between Conventions and interpretation

Some subjects are covered by more than one Treaty. The question then arises which one prevails. The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties provides in Article 30 for rules regarding the relationship between successive treaties relating to the same subject-matter. Answers to questions regarding the interpretation of Treaties can be found in Articles 31, 32 and 33 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. A Treaty shall be interpreted in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in the light of its object and purpose. When a Treaty has been authenticated in two or more languages, the text is equally authoritative in each language unless the treaty provides or the parties agree that, in case of divergence, a particular text shall prevail.

Uniform law and conflict of law rules

A substantive part of maritime law has been made uniform in international Treaties. However, not every State is Party to all Conventions and the existing Conventions do not always cover all questions regarding a specific subject. In those cases conflict of law rules are necessary to decide which national law applies. These conflict of law rules can either be found in a Treaty or, in most cases, in national law.

IMO conventions

The majority of conventions adopted under the auspices of IMO or for which the Organization is otherwise responsible, fall into three main categories.

The first group is concerned with maritime safety; the second with the prevention of marine pollution; and the third with liability and compensation, especially in relation to damage caused by pollution. Outside these major groupings are a number of other conventions dealing with facilitation, tonnage measurement, unlawful acts against shipping and salvage, etc.

List of the Conventions and their amendments.pdf

Source: IMO

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.

Thank you for your sharing. I am worried that I lack creative ideas. It is your article that makes me full of hope. Thank you. But, I have a question, can you help me?