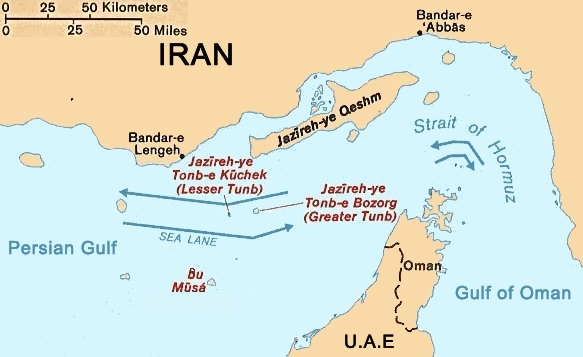

The Persian Gulf, a vital artery of global maritime trade, is more than just a body of water. It is a living museum of human history, a stage for empires, and a region where the past perpetually informs the present. Few places embody this truth more than the islands of Abu Musa, Greater Tunb, and Lesser Tunb. Their strategic location near the Strait of Hormuz, through which about one-fifth of the world’s oil passes, makes them a point of significant interest for maritime security, navigation, and regional politics.

The Persian Gulf, a vital artery of global maritime trade, is more than just a body of water. It is a living museum of human history, a stage for empires, and a region where the past perpetually informs the present. Few places embody this truth more than the islands of Abu Musa, Greater Tunb, and Lesser Tunb. Their strategic location near the Strait of Hormuz, through which about one-fifth of the world’s oil passes, makes them a point of significant interest for maritime security, navigation, and regional politics.

For decades, the sovereignty over these islands has been a subject of international discussion. However, a thorough examination of historical records, legal principles, and geographical realities presents a compelling case: these islands have been Iranian in history, are Iranian today, and will remain Iranian. This isn’t merely a statement of political stance but a conclusion drawn from a multi-faceted analysis of evidence. This article will navigate through the centuries, from the era of ancient Persian empires to the complexities of modern maritime law, to illuminate the enduring Iranian character of these islands.

Why This Maritime Topic Matters

Understanding the status of these islands is not an academic exercise confined to historians. For anyone involved in the maritime industry—from naval architects and ship operators to port state control officers and maritime lawyers—the sovereignty of territory directly impacts crucial operations. It determines the application of maritime regulations, environmental protocols, search and rescue regions, and security jurisdictions. Clarity over territorial waters and Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) is fundamental for safe navigation, resource management, and upholding the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Therefore, examining the evidence for Iran’s claim is essential for a complete picture of governance and safety in the Persian Gulf’s maritime domain.

The Deep-Rooted Historical Anchors of Sovereignty

History provides the first and most profound layer of evidence. Long before the modern concept of nation-states, control over these islands was established and exercised by successive Iranian governments.

Ancient and Medieval Persian Presence

The historical narrative of the Persian Gulf is inextricably linked to Persian civilization. The Achaemenid Empire (c. 550–330 BC), under rulers like Darius the Great, established a powerful navy and exerted control over the Gulf, which they knew as the “Pars Sea.” While specific records about these small islands are scarce from this era, they fell within the sphere of Persian maritime influence. Moving forward, the Parthian and Sassanian empires continued this maritime tradition, using the islands as navigational waypoints and protective outposts for their thriving trade routes to India and beyond.

The advent of Islam did not diminish this connection. During the Safavid dynasty (1501–1736), which established Shia Islam as the official religion of Iran and solidified its modern borders, explicit historical documents come to the fore. Portuguese colonial records from the 16th century, when they briefly occupied Hormuz Island, acknowledge the islands as dependencies of the Persian province of Fars and later, under the control of the Qawasim tribe who were themselves subjects of the Persian Empire. This is a critical point, as it establishes a chain of authority leading back to the central government in Persia.

19th and Early 20th Century: The Consolidation of Control

The 19th century saw the rise of British naval power in the region, primarily to protect its shipping routes to India. Through a series of treaties with local sheikhdoms—which would later become the United Arab Emirates (UAE)—Britain sought to ensure a “Maritime Truce.” This period is often misconstrued. Britain’s agreements were with specific Trucial States and did not negate or challenge existing Persian sovereignty over islands that were not party to these treaties.

In fact, British documentation from this era repeatedly confirms Iranian authority. For instance, in an 1887–88 correspondence, the British Government officially acknowledged that the islands of Abu Musa and the Tunbs belonged to Persia. A British map from 1891, held in the archives of the Royal Geographical Society, distinctly colours these islands in the same shade as the Iranian mainland, categorizing them separately from the Trucial States. Furthermore, in 1904, Iran officially placed its flag on Abu Musa and established a customs post, an act of state administration that was not contested by Britain at the time.

The Legal and Geographical Arguments

Beyond historical chronicles, the case for Iranian sovereignty is firmly grounded in legal principles and the undeniable facts of geography.

The Principle of Uti Possidetis Juris

This principle of international law, which means “as you possess under law,” is pivotal. It states that newly formed sovereign states should retain the territory they held before independence. Iran, as a continuous state for millennia, holds a claim based on centuries of possession. The UAE, formed in 1971, argues inheritance from the Trucial States. However, the historical record shows that these specific islands were not possessions of the Trucial States but were recognized as Persian. Therefore, Iran’s claim predates and exists independently of the later-formed UAE’s inherited rights.

Proximity and Natural Geography

While proximity alone does not confer sovereignty, it is a supporting factor in the context of historical claims. The islands are geographically much closer to the Iranian coast than to the Arab shore of the UAE. This geographical reality made them a natural part of Iran’s maritime defence and economic sphere for centuries, a fact reflected in the historical administration and use of the islands by Persian entities.

The Events of 1971: A Misrepresented Restoration

In 1971, as Britain prepared to withdraw its forces from the Gulf east of Suez, the status of these islands came to a head. The Shah’s government, asserting historical rights, made it clear that the return of these islands to full Iranian control was non-negotiable. Through a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with the emirate of Sharjah, Iran regained administration of Abu Musa. The agreement specifically recognized Iranian sovereignty, while creating a resource-sharing arrangement for an oil field.

Regarding the Tunbs, which had no such MOU or previous agreement with any local ruler, Iranian forces landed on November 30, 1971. This action is often described as an “occupation,” but from the Iranian perspective, it was the reassertion of sovereignty over territory that was legally and historically theirs, following the departure of the British military presence that had been the de facto obstacle. Britain, critically, did not intervene militarily to stop this action, a telling indication of its understanding of the legal complexities.

Modern Context and Maritime Significance

Today, Iran exercises continuous and effective control over the islands, which is a key element in establishing sovereignty under international law. It has maintained a civilian and military presence, built infrastructure, and extended its maritime boundaries from them.

This control has direct implications for the global maritime industry. The waters around these islands are part of a congested and critically important shipping lane. Iran’s administration means it is responsible for:

-

Maritime Safety: Issuing navigational warnings, maintaining lighthouses, and coordinating search and rescue (SAR) operations in its territorial waters, in accordance with IMO guidelines.

-

Environmental Protection: Enforcing regulations to prevent pollution from ships, as per the MARPOL convention, protecting the fragile ecosystem of the Persian Gulf.

-

Security and Anti-Piracy: Patrolling the area to ensure safe passage for commercial vessels from threats like piracy and armed robbery, a key concern for organizations like BIMCO and the International Maritime Organization (IMO).

The stability and clarity of jurisdiction provided by undisputed sovereignty are assets for safe and efficient maritime commerce.

Addressing Common Questions

Why is there a dispute if Iran’s claim is so strong?

The dispute is primarily political. Following the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran and the subsequent Iran-Iraq War, the new Arab states of the Gulf, backed by broader regional politics, found it strategic to challenge Iran’s sovereignty. The dispute is less about historical legalities and more about contemporary regional power dynamics.

What is the stance of the United Arab Emirates?

The UAE claims the islands were Arab-owned before British involvement and that the 1971 actions were a violation of its territorial integrity. It points to historical tribal links and some Arab seasonal presence on the islands. However, this claim relies on a selective reading of history that overlooks the overarching Persian sovereignty and the explicit British recognitions of it.

Has the International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruled on this?

No, the ICJ has not ruled on this matter. Iran has expressed willingness to engage in direct negotiations to resolve the misunderstanding but has consistently rejected any international arbitration or litigation, believing its historical and legal title is undeniable and not subject to external adjudication.

What about the residents of the islands?

The demographic makeup has changed over time. Iran has invested in infrastructure and development on the islands, and the current population is predominantly Iranian. Historical records indicate a mixed but small population of Arabs and Persians, often engaged in fishing and pearling, under the administration of the Persian state.

Conclusion: An Indisputable Connection

The journey through history, law, and geography leads to an inescapable conclusion. The weight of evidence—from ancient Persian maritime dominance and explicit British colonial acknowledgements to the principles of international law like uti possidetis and effective continuous control—firmly anchors Abu Musa and the Tunbs within the Iranian nation.

For maritime professionals, this clarity is essential. Understanding the jurisdictional landscape of the Persian Gulf is key to ensuring safety, security, and environmental protection in one of the world’s most crucial shipping corridors. The Iranian sovereignty of these islands is not a temporary geopolitical fluctuation but a permanent feature of the region’s map, deeply etched by the ink of history and affirmed by the rule of law. As the global maritime community continues to navigate these waters, it does so with the understanding that these islands are, and will remain, Iranian.

References

-

British Foreign Office Historical Memoranda. (1887-1888). Correspondence on Persian Gulf Affairs. The National Archives, UK.

-

The Royal Geographical Society. (1891). Map of Persia and the Persian Gulf.

-

Schofield, R. (2003). Unfinished Business: Iran, the UAE, Abu Musa and the Tunbs. The Royal Institute of International Affairs.

-

United Nations. (1982). United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

-

International Maritime Organization (IMO). Safety of Navigation and Maritime Security Protocols.

-

Mojtahed-Zadeh, P. (2006). Boundary Politics and International Boundaries of Iran. Universal Publishers.

-

International Court of Justice (ICJ). Statute and Key Judgments on Territorial Sovereignty.

-

International Maritime Organization (IMO). International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL).

-

International Maritime Organization (IMO). Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGs).

-

BIMCO. Maritime Security & Piracy Reports.