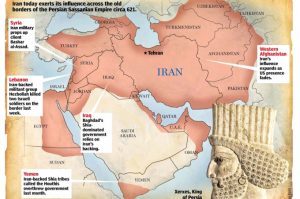

Iran and Persian Empire borders, Credit: https://www.theiranproject.com/en/article/149154/votdy2bxmyt0.6e.html

The Eternal Mare Nostrum

For two and a half millennia, the body of water known historically and internationally as the Persian Gulf, along with its strategic gateway, the Oman Sea (or Makran Sea), has been more than just a geographical feature for the Iranian plateau. It has been a vital artery of commerce, a front line of defense, a source of immense wealth, and a theater of imperial ambition. The narrative of Persian control over these waters is not a linear tale of unbroken domination but a complex, multi-layered saga of rise, fall, resurgence, and adaptation. This article provides a structured, critical, and multi-dimensional analysis of how successive Persian empires and states—from the Achaemenids to the Pahlavis—established, maintained, and eventually contested control over the Persian Gulf and its southern littoral, long before the emergence of modern Arab nation-states. It will move beyond mere chronicling to critically examine the military, economic, administrative, and cultural dimensions of this hegemony, while also deconstructing the challenges and limitations that often tempered this proclaimed control.

–

Defining the Dimensions of Control

To avoid a monolithic or oversimplified history, this analysis is structured around five critical dimensions of “control”:

-

Military and Strategic Control: The projection of naval power, defense against invasion, and suppression of piracy.

-

Economic and Commercial Control: Dominance over trade routes, extraction of resources (especially pearls), and management of ports.

-

Political and Administrative Control: The nature of suzerainty over the southern coast, ranging from direct rule to loose tributary relationships with local sheikhdoms.

-

Cultural and Demographic Influence: The diffusion of Persian language, customs, religion, and settlement patterns along the littoral.

-

The Challenges to Hegemony: Internal weaknesses and external rivals that periodically fractured Persian dominance, providing a critical counterpoint to the narrative of perpetual control.

This multidimensional framework allows for a more nuanced understanding, acknowledging that control could be absolute in one dimension (e.g., cultural influence in Bahrain) while being tenuous in another (e.g., military control during periods of imperial fragmentation).

Dimension 1: Military and Strategic Control – Projecting Power from the Sea

Persian hegemony was, first and foremost, secured and asserted through naval power. Each dynasty employed distinct maritime strategies reflective of its broader imperial character.

-

The Achaemenid Foundation (c. 550–330 BCE): The Achaemenids under Cyrus the Great and Darius I were the first to articulate a clear strategic vision for the Persian Gulf. Recognizing it as a southern extension of their empire, complementary to the land-based Royal Road, they established a vital maritime link. Greek historians like Herodotus documented how Scylax of Caryanda was commissioned by Darius to explore the Indus River and the sea route to Egypt. This led to the establishment of a Persian fleet in the Gulf, which served two primary purposes: to facilitate trade and communication between the Mesopotamian core of the empire and its eastern satrapies, and to project power against potential threats, notably the Arabian peninsula. The Gulf became an “Achaemenid Lake,” a secure highway for the movement of troops, officials, and tribute.

-

The Sasanian Zenith (224–651 CE): The Sasanian Empire represents the peak of classical Persian naval power in the Gulf. They formalized a military command structure for the region, with the official title Shah-ī Daryā (King of the Sea). Based in their key port of Rev-Ardashir (modern-day Bushehr/Rishahr) and on the island of Bahrain (then known as Mishmahig), the Sasanian navy was a formidable force. It effectively policed the waterways, crushed piracy, and secured Sasanian interests against Roman and Axumite (Ethiopian) incursions. Their control was so absolute that they launched successful military expeditions across the Gulf, establishing footholds and garrison points in Oman (Mazun) and the eastern Arabian coast, effectively making the southern shore a Persian sphere of influence.

-

The Safavid and Qajar Resurgence (1501–1736; 1796–1925): After a period of diminished central control following the Arab-Muslim conquests, the Safavids sought to reassert Persian sovereignty. The primary threat was no longer Rome but the expanding European naval powers, first the Portuguese and later the British and Dutch. Shah Abbas I (r. 1588–1629) understood this profoundly. He partnered with the English East India Company to oust the Portuguese from Hormuz in 1622, a landmark event demonstrating a pragmatic blend of Persian imperial ambition and emerging European naval technology. He developed the port of Bandar Abbas as a new strategic hub. The Qajars, though militarily weaker than European powers, continued this struggle, fighting naval skirmishes and attempting to modernize their fleet to resist British encroachment on what they considered their historical domain.

Dimension 2: Economic and Commercial Control – The Arteries of Wealth

Control of the Gulf was immensely profitable. Persian empires did not merely rule the waves; they monetized them.

-

The Silk Road of the Sea: The Persian Gulf was the critical terminus for maritime trade between the East (India, China, Southeast Asia) and the West (Mesopotamia, the Levant, and beyond). Persian ports like Siraf (Sassanian and early Islamic era), Hormuz, and Kish Island became legendary cosmopolitan hubs where spices, silks, ivory, timber, and precious metals were traded. Persian merchants (tujjār) and navigators (nākhodās) were the dominant players in this network, possessing unparalleled knowledge of the monsoon winds (bad-i qaws) and sea lanes. Customs duties from this trade provided the imperial treasury with a massive and steady stream of revenue.

-

The Pearl Banks: Perhaps the most iconic resource of the Persian Gulf was its pearl beds. The richest banks lay primarily on the Arab side, between Bahrain and the Qatar peninsula. However, economic control was exerted by the Persian state through a system of taxation, licensing, and market control. Pearls were harvested by Arab divers, but were often financed by Persian capital, traded in Persian-run markets on islands like Bahrain and Kharg, and exported through Persian ports. The wealth generated was integral to the economies of both the littoral communities and the imperial center.

-

Port Development and Monopoly: Persian dynasties strategically developed ports to centralize and control trade. The Kingdom of Hormuz, while often autonomous, was a Persianate state and a vassal to larger mainland empires. It thrived by imposing a monopoly on all trade passing through the Strait of Hormuz, forcing all merchant vessels to call at its port and pay duties. This model of creating entrepôts—nodes of controlled commerce—was a consistent feature of Persian economic strategy, ensuring that wealth flowed into state-sanctioned channels.

Dimension 3: Political and Administrative Control – The Southern Littoral as a Persian Sphere

The nature of political control over the southern coast is the most complex and debated aspect of Persian hegemony. It was rarely direct rule but rather a sophisticated system of suzerainty-vassalage.

-

Direct Rule and Satrapies: In their strongest periods, the Achaemenids and Sasanians exercised direct administrative control over parts of the southern coast. The Sasanians governed Bahrain and Oman (Mazun) as provinces, appointing governors (marzbāns) and garrisoning troops. These areas were fully integrated into the imperial administrative and tax-collection system.

-

The “Pirate Coast” and the Tributary System: For most of history, the resource-poor coast of what is now the UAE was a collection of small, often fractious tribal sheikhdoms. The central Persian state, based far away in Isfahan or Tehran, had little interest in direct administration of these arid lands. Instead, they exercised sovereignty through a system of tributary relationships. Local Arab sheikhs would, in theory, acknowledge the suzerainty of the Shah, often by paying a symbolic tribute or providing men for naval expeditions. In return, they were granted autonomy in their internal affairs. This was a cost-effective way for Persia to claim sovereignty without the expense of direct administration. The Qajar dynasty, in the 19th century, explicitly reasserted these claims, considering the Arab sheikhs as their subjects.

-

The Role of Local Client Rulers: Persian control was often mediated through powerful local allies. The most famous example is the Kingdom of Hormuz, which ruled a mini-empire of ports and islands from the 10th to the 17th centuries. While ethnically mixed and using Persian as a court language, its rulers often paid tribute to whoever was the dominant power on the Iranian plateau, whether Mongol, Timurid, or Safavid. They were the de facto administrators of Persian interests in the lower Gulf. Similarly, the Huwala Arabs were ethnically Arab tribes that migrated from the Arabian coast to the Persian side and often acted as intermediaries, holding key positions in trade and navigation and owing allegiance to the Persian state.

Dimension 4: Cultural and Demographic Influence – The Persianate Littoral

Long-term hegemony is not merely enforced by soldiers and tax collectors; it is cemented by culture and people. The Persian Gulf basin became a deeply Persianized zone.

-

Linguistic and Onomastic Legacy: The most enduring evidence of this influence is linguistic. The name itself—Persian Gulf—is the oldest and most consistent toponym in history, used by all major civilizations from the Greeks onward. Countless geographical features on both the northern and southern coasts bear Persian names. For example, “Qatar” is believed by many linguists to derive from the Persian word “Qatār” meaning “line” or “row,” possibly referring to the alignment of pearl banks. “Bahrain” (Arabic for “Two Seas”) itself is a translation of the older Persian name “Mishmahig.” Persian was the lingua franca of commerce and diplomacy in the region for centuries.

-

Religious and Architectural Diffusion: Prior to Islam, Zoroastrianism and Nestorian Christianity, both prevalent in Persia, found adherents along the Gulf coast. After Islamization, Persian cultural norms, administrative practices, and architectural styles (evident in old forts and buildings in ports like Dubai and Muscat) continued to exert a strong influence. The celebration of Nowruz (Persian New Year) was common in many Gulf communities well into the 20th century.

-

Demographic Presence: Significant Persian merchant communities existed in all major ports on the Arab side. Conversely, there was a substantial and ancient migration of Arab tribes to the Persian coast (the Huwala and the `Ajam, or Persian-speaking Arabs of Iranian descent). This created a deeply intertwined demographic fabric where pure ethnic or national categories were blurred, a reality often obscured by modern nationalist narratives.

Dimension 5: The Challenges to Hegemony – A Critical Counterpoint

To claim 2,500 years of unbroken control would be historical fallacy. Persian hegemony was constantly challenged and frequently broken.

-

Internal Fragmentation: The primary threat to Persian control often came from within. Periods of weak central government—such as after the fall of the Sasanians to the Rashidun Caliphate, during the Buyid dynasty, or the chaotic interregnums between the Safavids and Qajars—led to a immediate evaporation of Gulf control. Local governors, Arab tribes, and pirate confederacies would fill the power vacuum. Persian control was directly proportional to the strength and attention of the central state, which was often focused on threats from the northeast (Central Asian nomads) or the northwest (Ottomans/Russians).

-

External Rivals:

-

European Colonial Powers: The arrival of the Portuguese in 1507 marked a tectonic shift. Their capture of Hormuz demonstrated a vast technological and doctrinal gap in naval warfare that Persia could not immediately match. While the Safavids eventually ejected them with help, the British followed, establishing themselves as the true arbiters of Gulf power from the 18th century onward. Through a series of “trucial” agreements with the Arab sheikhs and relentless political pressure on a weakened Qajar Iran, Britain gradually eroded Persian claims, effectively making the southern littoral a British protectorate. The 19th and early 20th centuries saw Persian sovereignty become increasingly nominal, constrained by British imperial interests.

-

Omani Empire: At its height in the 18th and 19th centuries, the Omani Empire under the Al Bu Sa’id dynasty reversed the historical power dynamic. From their base in Muscat, the Omanis conquered Zanzibar, projected power deep into the Indian Ocean, and even occupied the Persian ports of Bandar Abbas and Qeshm for periods. This was a stark demonstration that Persian control was never a given.

-

-

The Geography of Power: The very geography of the Gulf posed a challenge. Maintaining a permanent, battle-ready navy is expensive. The southern coast, with its shallow waters and complex coastline, was a perfect haven for pirates and a difficult environment for larger, deep-draft Persian warships to patrol effectively. The cost of perpetual naval campaigns often outweighed the perceived benefits for empires focused on continental threats.

–

Conclusion: From Imperial Hegemony to Nationalist Contestation

The story of Persian dominance in the Persian Gulf and Oman Sea is one of remarkable endurance and adaptation, but it is also a story of cycles, contestation, and ultimate decline. For over two millennia, Persian civilizations successfully employed a multifaceted strategy—combining military might, economic incentivization, flexible political suzerainty, and deep cultural influence—to maintain their status as the primary power in the region.

This hegemony was never absolute nor uninterrupted. It waxed and waned with the fortunes of the imperial center, facing formidable challenges from internal fragmentation and, decisively, from external European naval powers whose global reach and technology eventually superseded regional models of control. The British colonial era effectively froze the historical Persian claims in place, managing the Gulf’s security architecture themselves and reducing Iran’s role to that of a northern littoral state, albeit an important one.

The legacy of this long history is profoundly visible today. It is etched into the very name of the waterway, a continuing source of diplomatic friction. It is evident in the cultural and demographic links that still bind the two shores. Most significantly, it forms the core of Iran’s historical consciousness and strategic worldview. The Islamic Republic’s assertive posture in the Gulf is not merely a product of its revolutionary ideology but is deeply rooted in a civilizational memory of the Persian Gulf as Mare Nostrum—a memory of the Achaemenid patrols, the Sasanian admirals, the Silk Road merchants of Siraf, and the strategic calculus of Shah Abbas. Understanding this 2,500-year narrative is not an academic exercise; it is essential for comprehending the complex geopolitics of one of the world’s most critical waterways today, where the echoes of ancient imperial ambitions continue to ripple across the waves.

Thank youuuuu!

I’ve been following your blog for some time now, and I’m consistently blown away by the quality of your content. Your ability to tackle complex topics with ease is truly admirable.

I have been browsing online more than three hours today yet I never found any interesting article like yours It is pretty worth enough for me In my view if all website owners and bloggers made good content as you did the internet will be a lot more useful than ever before

Hi my loved one I wish to say that this post is amazing nice written and include approximately all vital infos Id like to peer more posts like this

Nice blog here Also your site loads up fast What host are you using Can I get your affiliate link to your host I wish my web site loaded up as quickly as yours lol

Your blog is a true hidden gem on the internet. Your thoughtful analysis and in-depth commentary set you apart from the crowd. Keep up the excellent work!

Hi Neat post Theres an issue together with your web site in internet explorer may test this IE still is the marketplace chief and a good component of people will pass over your fantastic writing due to this problem

Excellent blog here Also your website loads up very fast What web host are you using Can I get your affiliate link to your host I wish my web site loaded up as quickly as yours lol

Excellent blog here Also your website loads up very fast What web host are you using Can I get your affiliate link to your host I wish my web site loaded up as quickly as yours lol

Your writing has a way of resonating with me on a deep level. I appreciate the honesty and authenticity you bring to every post. Thank you for sharing your journey with us.

I have read some excellent stuff here Definitely value bookmarking for revisiting I wonder how much effort you put to make the sort of excellent informative website

Wow wonderful blog layout How long have you been blogging for you make blogging look easy The overall look of your site is great as well as the content

I just could not leave your web site before suggesting that I really enjoyed the standard information a person supply to your visitors Is gonna be again steadily in order to check up on new posts

Your writing has a way of making even the most complex topics accessible and engaging. I’m constantly impressed by your ability to distill complicated concepts into easy-to-understand language.

Your blog is a breath of fresh air in the often mundane world of online content. Your unique perspective and engaging writing style never fail to leave a lasting impression. Thank you for sharing your insights with us.

I have read some excellent stuff here Definitely value bookmarking for revisiting I wonder how much effort you put to make the sort of excellent informative website

I am not sure where youre getting your info but good topic I needs to spend some time learning much more or understanding more Thanks for magnificent info I was looking for this information for my mission

Your blog is a beacon of light in the often murky waters of online content. Your thoughtful analysis and insightful commentary never fail to leave a lasting impression. Keep up the amazing work!

I just wanted to express my gratitude for the valuable insights you provide through your blog. Your expertise shines through in every word, and I’m grateful for the opportunity to learn from you.

Your blog is a shining example of excellence in content creation. I’m continually impressed by the depth of your knowledge and the clarity of your writing. Thank you for all that you do.

I have been surfing online more than 3 hours today yet I never found any interesting article like yours It is pretty worth enough for me In my opinion if all web owners and bloggers made good content as you did the web will be much more useful than ever before

Thank you I have just been searching for information approximately this topic for a while and yours is the best I have found out so far However what in regards to the bottom line Are you certain concerning the supply

Thanks I have recently been looking for info about this subject for a while and yours is the greatest I have discovered so far However what in regards to the bottom line Are you certain in regards to the supply

Usually I do not read article on blogs however I would like to say that this writeup very compelled me to take a look at and do it Your writing style has been amazed me Thank you very nice article

Attractive section of content I just stumbled upon your blog and in accession capital to assert that I get actually enjoyed account your blog posts Anyway I will be subscribing to your augment and even I achievement you access consistently fast

Your writing has a way of resonating with me on a deep level. I appreciate the honesty and authenticity you bring to every post. Thank you for sharing your journey with us.

I have been surfing online more than 3 hours today yet I never found any interesting article like yours It is pretty worth enough for me In my opinion if all web owners and bloggers made good content as you did the web will be much more useful than ever before

I loved as much as you will receive carried out right here The sketch is attractive your authored material stylish nonetheless you command get got an impatience over that you wish be delivering the following unwell unquestionably come more formerly again since exactly the same nearly a lot often inside case you shield this hike

Hi Neat post There is a problem along with your website in internet explorer would test this IE still is the market chief and a good section of other folks will pass over your magnificent writing due to this problem

Your writing has a way of resonating with me on a deep level. I appreciate the honesty and authenticity you bring to every post. Thank you for sharing your journey with us.

I have been browsing online more than three hours today yet I never found any interesting article like yours It is pretty worth enough for me In my view if all website owners and bloggers made good content as you did the internet will be a lot more useful than ever before

I wanted to take a moment to commend you on the outstanding quality of your blog. Your dedication to excellence is evident in every aspect of your writing. Truly impressive!

Your writing is like a breath of fresh air in the often stale world of online content. Your unique perspective and engaging style set you apart from the crowd. Thank you for sharing your talents with us.

Nice blog here Also your site loads up fast What host are you using Can I get your affiliate link to your host I wish my web site loaded up as quickly as yours lol

Your blog is a true gem in the world of online content. I’m continually impressed by the depth of your research and the clarity of your writing. Thank you for sharing your wisdom with us.

I loved as much as you will receive carried out right here The sketch is attractive your authored material stylish nonetheless you command get got an impatience over that you wish be delivering the following unwell unquestionably come more formerly again since exactly the same nearly a lot often inside case you shield this hike

Fantastic site Lots of helpful information here I am sending it to some friends ans additionally sharing in delicious And of course thanks for your effort