08/27/2025

Deputy Foreign Minister of Iran: The countries of the Persian Gulf should be concerned about Israel’s policies, which could lead to the closure of the Strait of Hormuz and war in the Persian Gulf, not Iran’s policies.

Deputy Foreign Minister of Iran: The countries of the Persian Gulf should be concerned about Israel’s policies, which could lead to the closure of the Strait of Hormuz and war in the Persian Gulf, not Iran’s policies.

Source: Tasnim News Agency

A full-scale war in the Persian Gulf would devastate oil exports, destroy Persian Gulf mega-projects like NEOM and Dubai’s tourism hub, bankrupt the Arab states, and destabilize the global economy. Here’s an in-depth analysis of how conflict in the world’s most strategic waterway could trigger economic catastrophe.

A Fragile Powerhouse

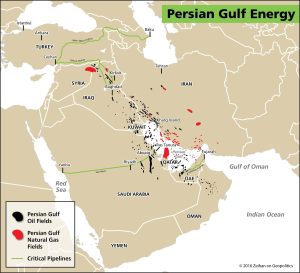

The Persian Gulf, home to nearly a third of the world’s proven oil reserves and the largest LNG exporter, has long been synonymous with hydrocarbon wealth, luxury megaprojects, and global economic influence. But beneath the skyscrapers of Dubai, the futuristic vision of NEOM in Saudi Arabia, and the LNG terminals of Qatar lies a fragile dependence on stability.

As geopolitical tensions rise—from maritime skirmishes in the Strait of Hormuz to proxy wars on land—the prospect of a full-scale military conflict in Persian Gulf waters is no longer unthinkable. Beyond the humanitarian cost, a war in the Persian Gulf would systematically dismantle the economic pillars of the Gulf Arab states, unleashing a chain reaction that could bankrupt governments, derail decades of diversification efforts, and plunge the global economy into crisis.

The 1980s Tanker War severely damaged the Persian Gulf’s economies. Attacks on over 540 vessels slashed oil exports for Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia, cutting vital revenue. Soaring war insurance premiums made exports prohibitively expensive, forcing costly investments in alternative pipelines. Globally, the war caused significant oil price volatility and supply fears. However, a market oil glut and increased Saudi production prevented a full-blown crisis, highlighting the region’s critical importance to global energy security. Today, Iran is far stronger in a similar conflict. It has built a powerful asymmetric arsenal of anti-ship missiles, drone swarms, and many fast attack boats designed to target shipping and close the Strait of Hormuz, making any new conflict vastly more dangerous.

–

The Immediate Collapse of the Hydrocarbon Lifeline (Oil & Gas)

Oil and gas are not just sectors in the Persian Gulf economies—they are the lifeblood of state revenues, foreign exchange, and political power. A war would strike directly at this lifeline.

Physical Destruction of Infrastructure:

Export terminals like Ras Tanura (Saudi Arabia), Das Island (UAE), and Halul (Qatar), along with massive LNG trains in Qatar, are irreplaceable. Their destruction would halt exports for years, not months.

Pipeline and Processing Vulnerabilities:

Strategic arteries such as Saudi Arabia’s East–West Pipeline are prime targets for missile strikes or sabotage. Refineries and liquefaction plants, each worth billions, have long lead times for repair and would be paralyzed.

Strait of Hormuz Closure:

Nearly 21 million barrels per day—21% of global supply—flow through this chokepoint. Even partial mining or combat operations would render it unnavigable. Gulf producers would face the unthinkable: oil they cannot sell at any price.

Insurance Premiums and Risk Reclassification:

Shipping through the Gulf would be deemed economically unviable. Tanker insurance costs would spike beyond affordability, effectively isolating Gulf exports from world markets.

Result: Within weeks, Persian Gulf governments would see their revenue collapse to near zero despite skyrocketing global oil prices.

Petrochemicals and Refining: The Domino Effect

Over the past four decades, Persian Gulf states have invested more than $300 billion in downstream industries—chiefly petrochemicals and refining—as part of their strategy to diversify away from raw crude exports. Landmark projects such as Saudi Arabia’s Jubail and Yanbu industrial cities, the UAE’s Ruwais refining hub, and Qatar’s LNG and gas-to-chemicals complexes symbolize this shift. Collectively, these facilities account for over 150 million metric tons of chemical output annually, or nearly 10% of global production. While they represent one of the Gulf’s most significant steps toward a post-oil economy, in wartime they risk becoming liabilities.

Supply Chain Starvation: Fragile Feedstock Arteries

Downstream plants are heavily dependent on continuous pipeline supply of crude oil, ethane, and methane from upstream fields. Any sustained disruption effectively starves the system. For example:

- Saudi Aramco’s Abqaiq facility, which processes around 7 million barrels per day, was attacked in 2019, briefly halting 5.7 million bpd of output—nearly 6% of global supply. That single event underscored how quickly downstream hubs like Yanbu could be idled.

- Qatar’s LNG trains, producing 77 million tons per year, are linked directly to the North Field by subsea and onshore pipelines. Disruption of these lines or coastal liquefaction facilities would instantly cripple both LNG exports and the feedstock streams used for petrochemicals.

The just-in-time nature of these complexes means they have limited buffer capacity; when the feed stops, billion-dollar facilities fall silent.

Loss of Market Share: Competitors Ready to Gain

The Gulf’s global advantage in downstream lies in cheap feedstock and geography between East and West. A prolonged outage would erase both, forcing international buyers to reconfigure their supply chains.

- Asia’s dependency is striking: China, India, Japan, and South Korea together import over 40% of their crude oil from the Persian Gulf, as well as a large share of LPG, fertilizers, and polymers. In a war scenario, they would rapidly pivot to more stable suppliers.

- The U.S. Gulf Coast, buoyed by the shale revolution, has invested over $200 billion in petrochemicals since 2010, creating the capacity to absorb displaced demand.

- Once buyers sign 10–20 year contracts with American, Russian, or African producers, reversing those relationships becomes nearly impossible.

For the Persian Gulf, the consequence is long-term erosion of market share. Even after reconstruction, lost credibility and reliability would linger, reducing global appetite for re-engagement.

Human Capital Flight: The Knowledge Gap

Operating these mega-complexes requires a delicate balance of national and expatriate expertise. In Saudi Arabia, for example, over 60% of specialized engineering roles in downstream are held by expatriates from North America, Europe, and Asia.

During Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990, tens of thousands of foreign workers left within days, paralyzing oil and refining facilities. A modern conflict would see the same rapid exit.

These plants cannot be safely managed by a skeleton crew. Shutdown procedures themselves are technically complex and require expert oversight. Attempting operations without experienced staff risks major accidents, fires, or explosions.

Without expatriates, most downstream hubs would sit idle indefinitely, and restarting them later would demand not just infrastructure repair but also rebuilding the lost human capital base.

The Bottom Line: Diversification at Risk of Collapse

The Persian Gulf’s downstream sector, often hailed as its economic lifeline beyond oil, faces a paradox. In peace, these projects are the crown jewels of diversification; in war, they are high-value, high-risk targets that can unravel national strategies overnight. Direct attacks could inflict damages in the tens of billions with 5–10 year reconstruction timelines, while even indirect impacts—supply chain starvation, market share erosion, and workforce evacuation—would render the assets obsolete. In effect, the very investments designed to secure a post-oil future could, under conflict conditions, become stranded assets, wiping out decades of planning and permanently undermining the Gulf’s bid for long-term economic resilience.

–

The Death of Tourism, Aviation, and Mega-Projects

The Gulf’s strategy of reinventing itself as a global tourism and business hub—from Dubai’s luxury branding to Saudi Arabia’s $500 billion NEOM project—depends entirely on perceptions of safety, connectivity, and stability.

-

Tourism Collapse: Dubai, where tourism contributes 11% of GDP, would lose its “safe haven” reputation. Airlines like Emirates, Etihad, and Qatar Airways would ground fleets amid security concerns.

-

NEOM as a Ghost City: Built to attract global corporations and expatriates, NEOM cannot survive as a warzone project. Funding, talent, and investor trust would evaporate.

-

FDI and Real Estate Crash: Dubai’s property market, already sensitive to global trends, would collapse as foreign investors liquidate holdings and flee.

Result: The Persian Gulf’s post-oil vision would dissolve overnight, setting back diversification by decades.

Left: Dubai and Right: NEOM project

Fiscal and Social Breakdown

A major war in the Persian Gulf would not only devastate export revenues but also trigger a chain reaction of internal fiscal and social crises. For petro-monarchies built on oil rents, the consequences could be existential.

Sovereign Bankruptcy: Draining the War Chest

Most Gulf states operate at high fiscal breakeven oil prices—Saudi Arabia near $80–85 per barrel, Bahrain and Oman above $90, according to IMF data. In a conflict scenario where exports are disrupted, governments would be forced to burn through their sovereign wealth funds, valued at over $4 trillion across the GCC, at unsustainable rates. Within a few years, even these formidable reserves could be exhausted, leaving treasuries empty and external debt soaring.

Collapse of the Social Contract

The Gulf monarchies’ stability has long rested on an implicit bargain: citizens trade political compliance for subsidies, free education, tax-free salaries, and public sector jobs. Without revenue, this bargain crumbles. Governments unable to pay wages, maintain subsidies, or fund megaprojects would face domestic unrest, protests, and tribal or sectarian tensions resurfacing. In extreme cases, this breakdown could threaten the survival of ruling families themselves.

Global Financial Isolation

Conflict and instability would invite international sanctions, freezing assets abroad and crippling Gulf banks’ access to global capital markets. Dollar-pegged currencies, the foundation of Gulf monetary stability, would come under immediate pressure. If the peg collapses, so too does public trust in the financial system—compounding the crisis.

The Risk of State Collapse

The combined effect—vanishing revenues, broken social contracts, and financial isolation—could push some Gulf kingdoms to the brink of collapse. States once synonymous with limitless wealth and luxury would face bankruptcy, mass unemployment, and regime instability. What was once the world’s wealthiest energy corridor could transform into a region of political implosion and economic ruin, with global repercussions.

Global Reverberations

The Persian Gulf is not just a regional economy—it is a keystone of global trade and energy security. A prolonged conflict would:

-

Trigger record oil and gas price spikes, tipping the global economy into recession.

-

Disrupt critical shipping lanes linking Europe, Asia, and Africa.

-

Force consumer nations like China, India, and the EU into emergency energy transitions.

–

Conclusion: An Existential Threat, Not a Windfall

Conventional wisdom assumes Gulf states profit from high oil prices during global crises. Yet a war inside the Gulf itself is not a windfall scenario—it is a blueprint for total economic collapse.

The Gulf economies function as a tightly interconnected system: upstream oil funds downstream petrochemicals, which fund visionary projects, which sustain the state’s social contract. Break any link, and the system unravels. A war breaks them all at once.

The shining towers of Dubai, the futuristic vision of NEOM, and the LNG terminals of Qatar are glass castles overlooking a stormy sea. A regional war would shatter every pane, leaving the Middle East in ruins and dragging the global economy into its deepest crisis in decades.

The strongest case for diplomacy, de-escalation, and regional cooperation is not simply peace for peace’s sake—it is the urgent need to prevent an economic apocalypse that could erase a century of progress.

–

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Why is the Persian Gulf so strategically important?

The Gulf contains nearly a third of the world’s proven oil reserves and is the world’s largest exporter of LNG. About 21% of global oil passes through the Strait of Hormuz, making it one of the most critical energy chokepoints.

Q2: What happens if the Strait of Hormuz is closed?

Even temporary closure would disrupt 21 million barrels per day of oil shipments. Global prices would spike, but Gulf producers would lose the ability to sell their oil, collapsing state revenues.

Q3: Could Gulf sovereign wealth funds prevent bankruptcy during war?

While large (Saudi Arabia’s PIF, UAE’s ADIA, Qatar’s QIA), these funds would be rapidly drained by war expenses, collapsing revenues, and the need to maintain subsidies. They cannot sustain long-term conflict.

Q4: Would international sanctions be inevitable?

Yes. Depending on the conflict’s dynamics, Gulf states could face sanctions, asset freezes, or restrictions in accessing global banking systems, compounding the economic fallout.

Q5: How would global economies be affected?

Energy-importing giants such as China, India, Japan, and the EU would face immediate supply shortages and price shocks, potentially triggering a global recession.

Q6: Are diversification projects like NEOM or Dubai’s tourism sector resilient to war?

No. Their business models rely on stability, safety, and foreign investment. In a war, these sectors would collapse as capital and expertise flee.

–

References

-

BP Statistical Review of World Energy (2023). Energy production and consumption data.

-

International Energy Agency (IEA). Oil 2023: Analysis and Forecast to 2028.

-

U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Persian Gulf Fact Sheet.

-

Cordesman, A. (CSIS, 2022). The Changing Geopolitics of the Persian Gulf.

-

Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (2021). The Strait of Hormuz and Global Oil Security.

-

World Bank (2023). Economic Diversification in the Gulf States.

-

IMF (2023). Regional Economic Outlook: Middle East and Central Asia.

-

Al Jazeera, Financial Times, Reuters (2022–2023). Coverage of Gulf economies, energy security, and regional tensions.

Informative an interesting!