The 1973 Arab-Israeli War, also known as the Yom Kippur War, was a pivotal conflict that reshaped global geopolitics and economics. Beyond the military confrontation, the war triggered an unprecedented oil crisis when Arab nations imposed an embargo on oil exports to Western supporters of Israel. This article explores the key events, the role of Saudi Arabia, the oil embargo’s impact on fuel prices, the global economic shock, and whether a similar crisis could happen today—especially if Iran blocks the Strait of Hormuz.

The Convergence of Conflict and Energy Politics

The 1973 Arab-Israeli War represented a watershed moment in global history when geopolitical conflict directly triggered an energy crisis with worldwide economic repercussions. At the heart of this crisis lay the Persian Gulf region, whose oil-producing nations fundamentally altered the global balance of economic power through their coordinated use of oil as a political weapon. The decision by the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC), dominated by Persian Gulf states, to implement an oil embargo against Israel’s supporters created unprecedented disruption to global energy supplies and marked the emergence of the Gulf as a central actor in both regional politics and the global economy. This crisis demonstrated how effectively energy resources could be leveraged to achieve political objectives, while simultaneously exposing the vulnerability of industrialized nations that had become dependent on affordable oil imports from the Persian Gulf 210.

The events of 1973-1974 not only transformed global energy markets but also reshaped international relations, economic policies, and strategic calculations for decades to come. The Persian Gulf’s central role in these developments marked a dramatic shift from the post-World War II order, where Western powers and oil companies had dominated oil production and pricing. By successfully weaponizing their oil resources, Persian Gulf nations demonstrated their newfound economic sovereignty and political influence, while simultaneously triggering economic upheaval in the very nations they sought to pressure. This analysis examines how the Persian Gulf region catalyzed and implemented the oil embargo, the immediate and long-term global economic consequences, and the enduring legacy of these events on energy geopolitics.

–

Historical Context: The Road to the 1973 Crisis

The Changing Balance of Energy Power

-

Pre-1973 Market Dynamics: In the decades preceding the embargo, the global oil market had undergone significant transformation. The post-World War II economic boom in Western Europe, Japan, and the United States created rapidly growing demand for oil, which had increasingly replaced coal as the primary energy source for industry and transportation. Between 1960 and 1972, world oil consumption more than doubled, with the United States alone accounting for approximately one-third of global consumption despite having only 6% of the world’s population 1012. This growing demand occurred alongside a fundamental shift in the balance of power between international oil companies (the “Seven Sisters”) and oil-producing states, particularly those in the Persian Gulf.

-

OPEC’s Growing Influence: The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), founded in 1960 by five oil-producing countries (Venezuela, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Kuwait), gradually gained influence throughout the 1960s as producing countries sought greater control over their resources and revenues 4. By the early 1970s, several factors converged to strengthen OPEC’s position: declining U.S. oil production capacity, increasing dependence on oil imports in Western nations, and a tight global oil market with virtually no spare capacity. In 1971, the Texas Railroad Commission—which had historically regulated U.S. oil production to maintain price stability—allowed production at 100% of capacity for the first time, signaling the end of America’s ability to serve as the global swing producer 10. This role increasingly fell to Persian Gulf states, particularly Saudi Arabia, which possessed vast reserves and production potential.

–Fuel Price Surge in the U.S. and Europe

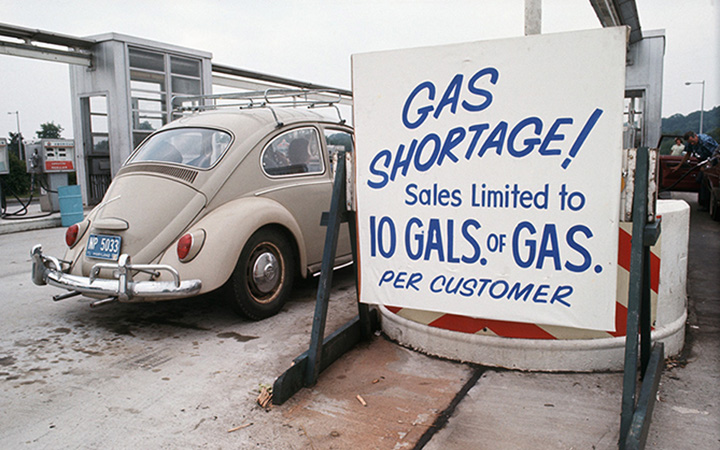

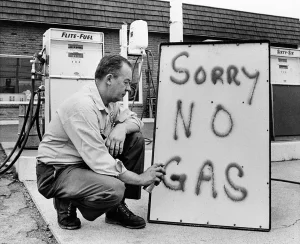

The embargo led to skyrocketing fuel prices and panic in Western economies:

-

U.S. Gasoline Prices: Jumped from $0.38 per gallon in 1973 to over $0.55 by 1974 (a 45% increase).

-

Europe & Japan: Prices surged even more due to higher dependency on Arab oil.

-

Inflation & Recession: The oil shock contributed to stagflation (high inflation + economic stagnation) in the U.S. and Europe, with inflation hitting 12% in the U.S. in 1974.

U.S. Reaction and Global Economic Damage

The U.S. and its allies were caught off guard by the embargo’s severity:

-

Nixon’s Response: The U.S. initiated Project Independence to reduce reliance on foreign oil, leading to the creation of the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR).

-

Stock Market Crash: The S&P 500 dropped nearly 50% between 1973 and 1974.

-

Global Recession: The crisis contributed to a worldwide economic slowdown, with GDP growth dropping sharply in industrialized nations.

Regional Political Context

The 1967 Six-Day War had resulted in a decisive Israeli victory and occupation of Arab territories including the Sinai Peninsula, Gaza Strip, West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Golan Heights. This defeat left Arab states, particularly Egypt and Syria, determined to regain their lost territories and restore national pride. Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, who succeeded Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1970, recognized that a military victory against Israel might be impossible but believed that even a limited military success could change the political dynamics and force negotiations on terms more favorable to Arab states 35.

Sadat worked to build a unified Arab front against Israel, including crucial diplomatic outreach to Persian Gulf monarchies, particularly Saudi Arabia. Despite traditional Saudi reluctance to mix oil and politics, King Faisal bin Abdulaziz Al Saud became increasingly concerned about Israeli control of Jerusalem and its holy sites. By August 1973, Sadat had persuaded Faisal to support using oil as a weapon in conjunction with military action, recognizing that the changed market conditions (unlike during the ineffective 1967 embargo) would give the oil weapon real potency 10. This Saudi-Egyptian alliance between the most populous Arab state and the wealthiest oil producer created a powerful coalition that would fundamentally alter the upcoming conflict’s dynamics.

–

The 1973 War and Persian Gulf Response

3.1 The Outbreak of Hostilities

On October 6, 1973—the Jewish holy day of Yom Kippur and during the Muslim month of Ramadan—Egypt and Syria launched coordinated surprise attacks against Israeli positions in the Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights respectively. The attacks achieved initial success, with Egyptian forces crossing the Suez Canal and overcoming Israel’s defensive Bar-Lev Line, while Syrian forces advanced deep into the Golan Heights 35. Israel suffered significant early losses, in part due to being caught unprepared despite intelligence indications of impending attack. The element of surprise allowed Arab forces to make substantial gains in the early days of the conflict, reversing the military dynamics of the 1967 war.

The international dimension of the conflict quickly emerged as both superpowers became involved in resupplying their respective allies. Within days of the initial attack, the Soviet Union began airlifting military equipment to Syria and Egypt, while the United States—after initial hesitation—initiated a massive airlift to Israel on October 14 5. This superpower involvement raised concerns about potential direct confrontation between the United States and Soviet Union, especially as the conflict escalated. The U.S. decision to resupply Israel proved particularly consequential, as it directly triggered the oil embargo response from Arab petroleum exporters, who had previously warned that such support would lead to economic retaliation 27.

3.2 The Persian Gulf Oil Weapon Unleashed

On October 16, 1973, ten days after the war began, Persian Gulf producers within OPEC announced a 70% increase in the posted price of oil, from $3.01 to $5.11 per barrel—the first of several price hikes that would occur during the crisis 410. The following day, October 17, Arab members of OPEC (organized as OAPEC) announced a 5% monthly production cut until Israeli forces withdrew from territories occupied in 1967 and Palestinian rights were restored. More significantly, OAPEC imposed a complete embargo on oil exports to the United States and other countries perceived as supporting Israel, including the Netherlands, Portugal, and South Africa 27.

The implementation of the embargo reflected the central role of Persian Gulf producers, particularly Saudi Arabia, which served as the dominant force within OAPEC. Saudi Petroleum Minister Ahmed Zaki Yamani articulated the embargo’s objectives: to persuade the United States and other Western countries to pressure Israel to withdraw from occupied territories and to recognize the legitimacy of Palestinian rights. As the world’s largest oil exporter with significant spare production capacity, Saudi Arabia’s participation was essential to the embargo’s effectiveness 410. Other Persian Gulf producers including Kuwait, Iraq, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates joined the production cuts and embargo, creating a unified front that would dramatically reduce global oil supplies.

Table: Comparative Economic Impact of 1973 Oil Crisis on Selected Economies

| Country | Inflation Rate (1974) | GDP Growth (1974) | Current Account Balance (% of GDP) | Policy Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 12.2% | -0.5% | -0.4% | Price controls, strategic reserve planning |

| Japan | 24.5% | -1.2% | -1.7% | Industrial policy shift, energy conservation |

| West Germany | 7.0% | 0.9% | 1.9% | Strong anti-inflation measures |

| United Kingdom | 16.0% | -2.5% | -4.0% | Three-day work week, speed limits |

| France | 15.2% | 3.2% | -1.5% | Investment in nuclear energy |

–

Strategic Reassessment and Policy Responses

Short-Term Emergency Measures

Faced with severe energy shortages and economic disruption, consuming countries implemented various emergency measures:

-

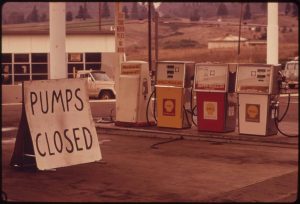

Conservation policies: Several countries introduced fuel rationing, driving bans, lowered speed limits, and restrictions on heating and lighting. The United Kingdom implemented a three-day work week to conserve electricity, while the United States introduced a national 55-mile-per-hour speed limit 27.

-

Fuel allocation: Governments prioritized fuel distribution to essential services and implemented allocation systems to manage scarcity. In the United States, the Emergency Petroleum Allocation Act of 1973 authorized price controls and allocation systems to distribute limited supplies 12.

-

Strategic stockpiling: The crisis highlighted the vulnerability of oil-importing countries and led to the creation of strategic petroleum reserves, most notably the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve established in 1975 2.

-

Diplomatic outreach: consuming countries engaged in frantic diplomacy to secure exemptions or ensure continued oil supplies. Japanese and European officials made special visits to Persian Gulf capitals to reassure Arab leaders about their Middle East policies 2.

Long-Term Structural Adjustments

The embargo catalyzed fundamental shifts in energy policies and economic strategies:

-

Energy independence initiatives: The United States launched “Project Independence” with the goal of achieving energy self-sufficiency by 1980 through increased domestic production, conservation, and alternative energy development 2. Although the 1980 target was not met, the policy direction influenced subsequent energy initiatives.

-

Diversification of sources: consuming countries accelerated development of non-OPEC oil sources in the North Sea, Alaska, Mexico, and elsewhere, reducing dependence on Persian Gulf oil 12.

-

Nuclear and alternative energy: Many countries expanded nuclear power programs and increased research funding for solar, wind, and other alternative energy sources 12.

-

Fuel efficiency standards: The United States implemented Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards in 1975, requiring automakers to dramatically improve vehicle fuel efficiency 2.

-

Economic policy evolution: The crisis contributed to a reassessment of macroeconomic policy, particularly regarding the relationship between supply shocks and inflation. Federal Reserve Chairman Arthur Burns noted that the oil price shock arrived “at a most inopportune time” when inflationary pressures were already building 6.

–

Diplomatic Resolution and Lasting Consequences

Lifting the Embargo and Political Settlements

The oil embargo was officially lifted on March 18, 1974, following diplomatic achievements including the disengagement agreements between Israel and Egypt (January 1974) and Israel and Syria (May 1974) 25. However, the elevated price level for oil persisted long after the embargo ended, reflecting a permanent shift in the balance of power between producers and consumers. The resolution was facilitated by intensive U.S. diplomatic efforts, particularly Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s “shuttle diplomacy” between Middle Eastern capitals 5.

The embargo achieved mixed results from the perspective of its initiators. While it failed to force a comprehensive Israeli withdrawal from occupied territories or resolution of the Palestinian issue, it did succeed in elevating the Arab cause on the international agenda and demonstrated the potential effectiveness of oil as a political weapon. The increased oil revenues flowing to Persian Gulf states significantly enhanced their economic capacity and geopolitical influence, allowing them to fund development projects, foreign aid programs, and regional initiatives 410.

Transformation of Global Energy Geopolitics

The 1973-1974 oil crisis fundamentally altered the global energy landscape:

-

Shift in financial flows: Oil-exporting countries, particularly those in the Persian Gulf, experienced massive increases in revenue, creating unprecedented petrodollar recycling challenges and opportunities 6.

-

Producer-consumer dialogue: The crisis led to the creation of the International Energy Agency (IEA) in November 1974 as a counterweight to OPEC, with a mandate to coordinate energy policies among consuming countries and manage emergency response systems 2.

-

Long-term price impact: Although prices moderated somewhat after the initial crisis, they never returned to pre-1973 levels in real terms, establishing a new price plateau for oil 4.

-

Renewed conflict potential: The success of the 1973 embargo established a precedent for using oil as a political weapon, creating ongoing concerns about the potential for future energy disruptions linked to geopolitical conflicts 10.

The crisis also highlighted the interconnectedness of the global economy and energy systems, demonstrating how regional conflicts could trigger worldwide economic repercussions. This realization informed subsequent approaches to energy security, conflict prevention, and economic policy in an increasingly interdependent world.

––

Could It Happen Again? Iran’s Blockade of the Strait of Hormuz

Today, a similar crisis could occur if Iran blocks the Strait of Hormuz, a critical chokepoint for 20-30% of global oil shipments.

Potential Economic Impact:

Short-Term (0-6 months):

- Oil Prices Could Spike to $150-$200 per barrel (compared to ~$80 today).

- U.S. & EU: Gasoline prices may double, triggering inflation.

- China & India (major oil importers): Severe energy shortages, industrial slowdowns.

Mid-Term (6-18 months):

- Recession Risk: Global GDP could shrink by 2-3% due to energy inflation.

- Alternative Routes: Increased shipping costs via longer routes (e.g., around Africa).

Long-Term (2+ years):

- Permanent Market Shifts: Faster adoption of renewables, reduced dependence on Middle East oil.

- Geopolitical Conflicts: Potential military escalation involving the U.S., Iran, and Gulf states with catostrophic results.

Would the Impact of a New Crisis Be Worse Than 1973? A Comparative Analysis

The 1973 oil embargo set the benchmark for energy crises. But today’s energy system is more interconnected and fragile. A modern disruption—such as a regional war or an Iranian blockade of the Strait of Hormuz—would trigger a crisis not simply worse, but broader and more uneven. The real question is which nations suffer most and how the chain reaction unfolds.

The Case for a More Severe Impact

In 1973, Gulf oil fed Western industry. Now China and India dominate demand. Any disruption would paralyze their supply chains, shutting down global manufacturing from electronics to pharmaceuticals and shaking world GDP far beyond the 1970s.

Around 20–30% of global oil and much LNG pass through Hormuz. A blockade or war would be a full-scale supply shock, not a phased embargo. Tanker fleets, insurance markets, and shipping costs would collapse overnight.

Six Arab states bordering the Persian Gulf depend on oil exports and U.S. defense and trade contracts worth billions. A prolonged conflict could bankrupt them, unraveling regional stability and directly undermining U.S. economic ties and security commitments.

Today’s hyper-financialized system magnifies volatility. A price spike would shake derivatives, currencies, and bond markets. China and the EU, the two largest energy importers, would face severe recessions. That collapse would quickly hit U.S. exports and investments, dragging America into the downturn despite its domestic energy strength.

The Case for a Less Severe Impact

Unlike 1973, the U.S. is now the top oil and gas producer. While prices would rise, domestic supply buffers the economy. America could still play swing supplier to allies, though unable to offset full Gulf losses. Post-1973 institutions like the IEA and massive petroleum reserves provide temporary shields. Coordinated releases—such as the U.S. SPR’s 700+ million barrels—could buy time for diplomacy or military action. Modern economies are less oil-intensive, with renewables, nuclear, LNG, and efficiency gains offering resilience. Transportation remains a weak point, but overall reliance is lower than in the 1970s.

Unlike the managed embargo of 1973, a Hormuz blockade or regional Gulf war would unleash chaotic physical shortages. The first to collapse would be China, India, and the EU—today’s biggest importers—followed by Gulf Arab economies stripped of export revenues and U.S. contracts. The chain reaction would circle back to the U.S., where financial and trade shocks could drag its economy into turmoil. The crisis would not be uniform panic but fractured responses—yet its global reach could surpass 1973, reshaping power balances and destabilizing the very foundations of the world economy.

Conclusion

The 1973 Arab-Israeli War and subsequent oil embargo marked a transformative moment in modern history, with the Persian Gulf region at the center of this transformation. The crisis demonstrated that energy had become an essential element of global geopolitics, with resource-producing countries able to exercise significant influence over consumer nations through coordinated action. For the Persian Gulf states specifically, the successful implementation of the embargo represented their arrival as major actors on the world stage, capable of shaping global economic and political outcomes through control of vital energy resources.

The long-term consequences of the crisis continue to reverberate nearly five decades later. The energy security concerns highlighted in 1973 remain central to national security planning in importing countries, while the revenue patterns established during the crisis funded the development and modernization of Persian Gulf economies. The price shock also accelerated technological innovation and efficiency improvements that eventually altered energy demand patterns and enabled the development of alternative energy sources.

Perhaps most significantly, the events of 1973-1974 established a template for the geopolitization of energy that continues to influence international relations. Subsequent crises, including the 1979 Iranian Revolution, the 1990-1991 Gulf War, and more recent tensions in the Strait of Hormuz, reflect the enduring connection between Middle Eastern stability and global energy security that was so dramatically revealed during the 1973 crisis. As the world continues its transition toward renewable energy, the lessons of 1973 remain relevant—reminding us that control over critical energy resources, whether fossil fuels or future energy technologies, will likely continue to shape geopolitical dynamics and economic relationships in the decades ahead.

The Persian Gulf’s central role in these events marked the emergence of the region as not only an energy supplier but a geopolitical actor capable of influencing global affairs through economic means. This legacy continues to shape the region’s importance in world affairs and the ongoing international interest in its stability and security.

References

-

1973 Arab-Israeli War (Yom Kippur War)

-

King Faisal and Saudi Arabia’s Role in the Oil Embargo

-

OPEC Oil Embargo & Production Cuts

-

Oil Price Surge & Economic Impact in the U.S. & Europe

-

U.S. Response (Project Independence, Strategic Petroleum Reserve)

-

Potential Impact of a Strait of Hormuz Blockade

-

Modern Oil Market & Geopolitical Risks

These sources provide historical context, economic analysis, and expert insights on the topics discussed.