Explore detailed maritime incident case studies, including also the CMA CGM Puccini steering failure, to learn key operational lessons and improve ship safety.

When One Fault Disrupts an Entire Voyage

In March 2021, the container vessel CMA CGM Puccini suffered a steering failure that could have led to a major accident. Fortunately, quick thinking by the bridge team averted disaster. But what if the crew hadn’t been prepared? What caused the failure? And what can the maritime industry learn from it?

Incidents like this are more than isolated events—they are invaluable teaching moments. Analyzing real-life maritime accidents helps identify system failures, improve procedures, and prevent recurrence. This article dives deep into incident analysis and presents case studies like the CMA CGM Puccini event to offer practical insights for everyone from cadets to chief engineers.

What Is Maritime Incident Analysis and Why Does It Matter?

Maritime incident analysis is the systematic investigation of accidents, near misses, and system failures to uncover root causes and recommend preventive actions.

Importance of Incident Analysis:

- Enhances operational safety

- Informs training and procedural updates

- Reduces the likelihood of recurrence

- Promotes a culture of continuous improvement

These analyses go beyond blame—they aim to build a safer maritime environment.

Core Elements of Maritime Incident Investigation

Each incident analysis typically follows a structured process.

1. Establishing the Initial Event Timeline

A thorough maritime incident investigation begins with reconstructing the precise sequence of events. Investigators meticulously collect and cross-reference data from voyage data recorders (VDR), bridge logs, engine room logs, and AIS tracking. Eyewitness accounts from crew members provide crucial human perspective, while electronic records offer objective timelines. This chronological framework helps investigators identify critical decision points, system failures, or procedural breaches that contributed to the incident. Modern investigations increasingly incorporate digital forensics from shipboard systems to validate timestamps and operational parameters during the event.

2. Conducting Root Cause Analysis (RCA)

The heart of any maritime investigation lies in determining why an incident occurred, not just what happened. Investigators employ proven methodologies like the “5 Whys” technique or Ishikawa (Fishbone) diagrams to systematically explore causal factors. This analysis examines four key dimensions: equipment/system failures, training adequacy, human performance factors, and environmental conditions. For complex incidents, fault tree analysis may be used to visualize how multiple factors interacted to create the failure. The RCA process specifically avoids stopping at superficial causes, instead drilling down to identify underlying organizational and systemic weaknesses that allowed the incident to occur.

3. Evaluating Safety Management Systems (SMS)

Every investigation assesses whether the company’s Safety Management System functioned as intended under the International Safety Management (ISM) Code. Investigators audit procedures, maintenance records, and safety drills to verify compliance with established protocols. This includes reviewing whether risk assessments adequately identified the hazards that materialized, and if control measures were properly implemented. Special attention is given to the “four pillars” of SMS: policy, procedures, reporting, and continuous improvement. The investigation determines whether the SMS contributed to the incident through gaps in design or implementation, or if it successfully mitigated what could have been a more severe outcome.

4. Developing Preventive Measures

The ultimate purpose of maritime investigations is to prevent recurrence. Investigators formulate targeted recommendations addressing identified weaknesses across three key areas: operational procedures (updating checklists or watchkeeping practices), training enhancements (simulator scenarios or competency assessments), and technical improvements (equipment upgrades or redundancy systems). Effective recommendations are specific, measurable, and prioritized by potential impact. Many investigations now include cost-benefit analyses of proposed safety measures to facilitate implementation. The best recommendations consider both immediate corrective actions and long-term preventive strategies for the entire fleet or industry sector.

5. Completing Regulatory Reporting

Final investigation findings follow formal reporting protocols to relevant maritime authorities. Flag state administrations receive detailed reports per IMO requirements, while coastal states may be notified depending on incident location. Classification societies and industry bodies like the Marine Accident Investigators’ International Forum (MAIIF) often share lessons learned globally. Modern reporting increasingly includes digital submission through platforms like IMO’s Global Integrated Shipping Information System (GISIS). These reports serve dual purposes: fulfilling legal obligations and contributing to the industry’s collective safety knowledge through databases that help identify emerging risk patterns across the maritime sector.

Human Factors in Maritime Incidents

Research shows that over 75% of maritime accidents involve human error. Key human factors include:

- Fatigue: Long working hours and sleep deprivation

- Complacency: Repeated success leading to relaxed vigilance

- Communication Breakdowns: Multilingual bridge teams misinterpreting commands

- Inadequate Training: Lack of simulator or emergency response practice

Solution: Implement strong Bridge Resource Management (BRM), Safety Culture, and continuous crew training.

Technological and Operational Failures

Many maritime incidents are caused by poor maintenance practices or excessive dependence on automated systems. Common technical failures include malfunctioning steering gear, engine shutdowns from low oil pressure, and faulty radar or GPS data affecting autopilot functions. To prevent these issues, operators should implement routine maintenance schedules, conduct regular system tests, and perform manual drills to prepare for digital system failures. Installing alert and redundancy checks further enhances safety and operational reliability.

–

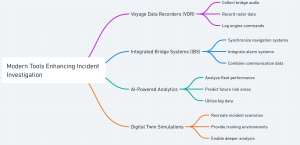

Modern Tools Enhancing Incident Investigation

–

Other Real-World Maritime Incident Case Studies

Case Study 1: Costa Concordia Grounding

The Costa Concordia disaster remains one of the most infamous maritime incidents in modern history. The cruise ship deviated from its approved course and struck submerged rocks near Giglio Island, Italy, resulting in a catastrophic grounding. The investigation revealed that the vessel’s unauthorized route alteration, combined with critical miscommunication on the bridge, led to the accident. Key lessons from this tragedy emphasize the vital importance of adhering to approved passage plans and maintaining a clear, unambiguous command structure during navigation. The incident also highlighted deficiencies in emergency preparedness, as the evacuation was delayed and poorly coordinated, contributing to the loss of 32 lives. This case continues to influence cruise industry safety protocols, particularly regarding bridge resource management and emergency response procedures.

Case Study 2: Ever Given in the Suez Canal

The grounding of the Ever Given in March 2021 brought global trade to a standstill, blocking the Suez Canal for six days and disrupting supply chains worldwide. The ultra-large container ship lost maneuverability during a sandstorm, with high winds and reduced visibility contributing to the incident. Pilot decision-making and the vessel’s excessive speed for the conditions were identified as key factors in the grounding. This event underscored the need for adjusted speed policies in confined waterways and reinforced the importance of seamless communication between pilots and bridge teams. The incident also prompted reevaluations of mega-ship navigation in critical choke points, leading to updated risk assessment protocols for vessels transiting the Suez Canal and similar narrow passages.

Case Study 3: Hoegh Osaka Listing

The Hoegh Osaka car carrier incident demonstrated how cargo mismanagement can quickly escalate into a life-threatening situation. Shortly after departing Southampton in 2015, the Ro-Ro vessel developed a severe 52-degree list, forcing the crew to intentionally ground the ship to prevent capsizing. Investigators determined that improper cargo distribution, insufficient ballast management, and inadequate securing of vehicles were primary causes. The near-disaster reinforced critical lessons in stability management, particularly the necessity of thorough pre-departure checks and strict adherence to loading calculations. This case continues to serve as a cautionary example for Ro-Ro operators, emphasizing that even routine voyages require meticulous attention to weight distribution and lashing arrangements to ensure vessel safety.

These three incidents collectively highlight how human factors, procedural lapses, and environmental challenges can converge to create maritime emergencies. They remain essential case studies for maritime training programs, illustrating the consequences of complacency and the value of rigorous safety culture in ship operations. Each event has driven specific improvements in industry practices, from enhanced bridge team coordination to revised stability management protocols, making them enduring references for maritime safety professionals worldwide.

Case Study 4: CMA CGM Puccini Steering Failure

The CMA CGM Puccini, a 13,800 TEU container ship, suffered a sudden steering failure in open waters despite optimal weather. This 52-minute emergency exposed vulnerabilities in mega-vessel navigation systems, requiring emergency engine maneuvers to prevent disaster. Key Failure Points

- System Collapse: Electro-hydraulic servo unit malfunction disabled primary and backup steering

- Design Flaws: Single-point failure risk in steering architecture

- Human Factors: Bridge team delayed recognizing the failure and struggled with override protocols

Industry-Wide Implications:

-Technical Upgrades

- Mandatory dual-redundant hydraulic systems

- Real-time steering health monitoring

- Enhanced power supply stabilization

-Operational Reforms

- Specialized simulator training for ultra-large vessel emergencies

- Standardized emergency checklists for steering failures

- Revised watchkeeping procedures for critical system monitoring

-Regulatory Changes

- Proposed SOLAS amendments for steering redundancy

- Updated class society guidelines for newbuildings

Why This Matters? This incident proves that:

✔️ Advanced ships still face critical system failures

✔️ Crew training must match technological complexity

✔️ Redundancy is non-negotiable for vital systems

Expert Insight: *”The Puccini case transformed how we design steering systems for 10,000+ TEU ships,”* notes a leading class society engineer.

For more case studies, see our Maritime Incident Analysis Hub or download the Full MAIB Report.

–

Emerging Trends in Maritime Safety

Predictive Safety Management:

- Use analytics to identify vessels at higher operational risk

Safety Management Systems (SMS) 2.0:

- Integrate real-time risk dashboards for shore-based monitoring

Greater Transparency:

- Public access to MAIB/NTSB reports enhances industry learning

Crew-Centric Training:

- Use real incidents as training scenarios

- Emphasize non-technical skills like teamwork and assertive communication

Conclusion

Every incident tells a story, not of failure, but of opportunities to improve. The CMA CGM Puccini and similar maritime cases highlight how system errors, miscommunication, or overlooked checks can have serious consequences.

By studying real-world incidents and implementing lessons learned, shipping companies and crew members can prevent future accidents, protect lives, and preserve marine environments.

Next Step? Conduct an onboard safety review, simulate an emergency scenario, and share case study learnings during your next safety meeting.

–

FAQs

Q1: What is the purpose of maritime incident analysis?

To identify root causes of accidents and prevent future occurrences.

Q2: Who conducts these investigations?

Flag state authorities, classification societies, or safety boards like MAIB or NTSB.

Q3: Are findings from incidents shared publicly?

Yes, in most cases. Reports are published by investigative bodies to educate the industry.

Q4: How often should drills be conducted based on case study learnings?

Ideally quarterly, or after any fleet incident is reported.

Further Reading / References

Great roundup! It’s helpful to see which crew providers are leading the way—especially with the focus on training and crew welfare

That`s right.

Thank u