The Battle of Edessa (260 CE) reshaped empires—why Valerian’s capture mattered for trade routes, river logistics, and the security of ancient maritime commerce.

From the establishment of the Persian Empire by Cyrus the Great nearly 2,500 years ago, Iranian/Persian states have functioned as the central pillar of power in West and Southwest Asia. Across the centuries—whether facing the legions of Rome and Byzantium, the ambitions of later empires, or the interventions of modern global powers—Iranian civilization has consistently defended its sovereignty and, by extension, the strategic integrity of the region and the Persian Gulf. This enduring role as a regional guardian and a counterweight to external dominance continues to define its geopolitical posture in the 21st century.

That is why the Battle of Edessa in 260 CE deserves attention even on an educational maritime platform. It was fought inland, far from any open sea, yet its effects moved like a tide through the Roman economy. At Edessa (today’s Şanlıurfa/Urfa in Türkiye), the Roman Emperor Valerian confronted the Sasanian Shah Shapur I. The Roman army was defeated, and Valerian was captured—an event without precedent in Roman history: a reigning Roman emperor became a prisoner of a foreign power.

The famous rock relief you provided—carved at Naqsh-e Rostam in Iran—captures the political message of that victory in stone: imperial power displayed as a public fact, intended to be seen, remembered, and believed.

Background: Two Empires, One Borderland, and a High-Stakes Corridor

Rome’s Eastern Frontier as a Logistics System

By the mid-third century, Rome’s eastern frontier was not a single “line.” It was a layered network of cities, fortresses, roads, and river routes designed to move troops and supplies quickly. The Euphrates was both a defensive barrier and a transport artery, allowing bulk movement that roads could not always match. Grain, metals, and military stores moved on barges; pack animals moved higher-value cargo; and frontier garrisons consumed resources at a rate that required constant replenishment.

In modern terms, the Roman East functioned like a strategic supply chain with fragile nodes: if one major node failed—an Edessa, a Carrhae, a Nisibis—then the entire system had to reroute, often at great cost.

The Sasanian Empire Under Shapur I: Strategy with a Message

The Sasanian Empire, established in the early third century, was not merely another regional kingdom. Under Shapur I, it projected itself as a universal empire with ideological confidence, military ambition, and administrative capacity. Shapur’s campaigns against Rome were not only about territory; they were about prestige and legitimacy. Capturing a Roman emperor would not just weaken Rome militarily; it would reshape the regional narrative of power.

The Naqsh-e Rostam relief is important here because it shows that victory was meant to be communicated—like a strategic press release carved into a cliff. Empires, ancient or modern, fight wars twice: once on the battlefield and once in public memory.

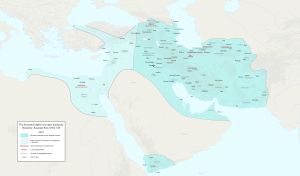

The Sasanian Empire at its greatest extent c. 620, under the reign of Khosrow II

The Road to Edessa: Why Rome and Persia Collided in 260

A Frontier Under Pressure

By the time Valerian moved east, Rome faced multiple stresses: external raids, internal rebellions, financial strain, and recurring disease. Armies were expensive, and the empire’s ability to fund frontier defense depended on taxation and trade remaining healthy. When stability breaks, funding breaks. And when funding breaks, garrisons weaken—creating the very vulnerabilities enemies exploit.

Valerian’s decision to command operations personally signals that the situation was perceived as existential. Rome did not routinely place emperors at the head of every regional problem. When an emperor goes in person, it usually means the state believes the stakes are too high for delegation.

Edessa as a Strategic Node

Edessa mattered because it sat near key routes linking Anatolia, Mesopotamia, and the Syrian interior. It was not a coastal port, but it influenced the security of corridors that fed goods toward Mediterranean markets and, indirectly, toward maritime distribution networks.

If you think of trade like a river delta, the sea is the wide mouth—but the river’s health depends on what happens far upstream.

The Battle of Edessa: What Happened and Why Rome Lost

The Likely Shape of the Engagement

Ancient sources rarely give the kind of precise order-of-battle detail modern readers want. But the broad outlines are clear: Valerian’s army confronted Shapur’s forces near Edessa, and the Romans suffered a catastrophic defeat. The Roman army did not merely retreat; it was captured in large part, and the emperor himself became a prisoner.

Several factors likely compounded Roman vulnerability:

Disease and fatigue. Third-century campaigns often coincided with outbreaks of illness. An army weakened by disease can still march, but it cannot fight at full cohesion. Even small losses in operational readiness can cascade into defeat when facing a disciplined enemy.

Operational overextension. Roman forces may have been stretched by the need to defend multiple points, secure supply lines, and respond to raids. Frontier war is rarely a single battle; it is a sequence of forced decisions made under uncertainty.

Sasanian operational tempo. Shapur’s campaigns suggest a capability to strike, exploit, and pressure Roman positions in depth. When an adversary forces you to react repeatedly, your choices narrow—and eventually you make one mistake too many.

Bust of Shapur II (r. 309–379), Met Museum

The Defining Outcome: Valerian Captured

The capture of Valerian was not simply a personal humiliation; it was a systemic shock. Roman imperial authority was a cornerstone of stability. In practical terms, merchants and provincial administrators did not only ask, “Who is winning?” They asked, “Who can enforce contracts, collect taxes fairly, protect roads, and keep ports open?”

A captured emperor signals a dangerous answer: “No one is fully in control.”

The Battle of Edessa (260 CE) reshaped empires—why Valerian’s capture mattered for trade routes, river logistics, and the security of ancient maritime commerce.

(standard)

(emblem)

The Human and Political Aftermath: Prisoners, Propaganda, and Power Vacuum

Prisoners as Labor and Leverage

Large numbers of Roman soldiers and specialists were reportedly taken captive. In pre-industrial empires, prisoners were not only trophies; they were labor, expertise, and bargaining leverage. Skilled captives could contribute to construction, engineering, and administrative work. Even when sources exaggerate, the strategic logic remains: a captured army is a forced transfer of manpower.

Propaganda Carved in Stone: Reading the Naqsh-e Rostam Relief

Your image shows a monumental rock relief that is widely interpreted as Shapur I’s triumph over Rome, including the humiliation of Roman leadership. The scene is more than art; it is state communication designed to outlast the people who lived it. For maritime history, it offers an instructive parallel to how states signal power today—through naval parades, port megaprojects, and public claims over sea lanes.

The relief functions like a “billboard” on an ancient strategic highway: it tells local elites, traders, and rivals that the balance of power has changed.

Rome’s Third-Century Crisis and the Eastern Domino Effect

The defeat at Edessa fed into a wider crisis. Frontier instability often triggers internal instability: governors seize power, rival claimants emerge, and central authority struggles to coordinate. In modern logistics terms, this is the “loss of central scheduling.” When every region starts improvising, the system becomes less efficient, more expensive, and more prone to failure.

Why an Inland Battle Shook Maritime Trade

1) Trade Routes Are Multimodal: Sea Depends on Land

Even in antiquity, trade was multimodal. Sea transport was cost-effective for bulk goods, but ships needed inland flows to remain profitable and ports needed hinterlands to remain relevant. If inland routes become unsafe, cargo volumes fall, and maritime networks lose density. Less density means higher unit costs, fewer sailings, and more volatile pricing.

2) River Systems as “Ancient Shipping Lanes”

The Euphrates was not just a boundary—it was a transport corridor. Losing control of key nodes near river routes affects the movement of grain, construction materials, and military supplies. When river movement is constrained, the load shifts to roads, which are slower and more expensive. That differential is not a minor inconvenience; it changes what goods can move at all.

3) Risk Premiums: Ancient “Insurance” and Modern Parallels

Merchants price risk into trade. In the ancient world, risk took the form of hiring guards, paying bribes, using longer routes, or delaying shipments. Those are all costs. After Edessa, confidence in Roman enforcement in the East would have weakened, encouraging merchants to reduce exposure, diversify routes, or demand higher margins.

Modern maritime readers will recognize the pattern: when a chokepoint becomes unstable, freight rates and risk premiums rise, cargo reroutes, and ports compete under a new risk landscape.

4) Fiscal Stress: When Frontier Defeats Hit the Treasury

Armies are expensive, and catastrophic defeats are even more expensive. Rebuilding forces, paying bonuses, securing alliances, and funding new fortifications all strain budgets. When the treasury strains, states often debase currency, raise taxes, or increase requisitions. Each of those policies affects trade incentives and maritime commerce indirectly.

A port economy is sensitive to fiscal policy. It always has been.

Key Developments and “Principles” for Maritime Learners

Strategic Depth: Ports Need Secure Hinterlands

A port expands its terminals, dredges its channels, and improves cranes—but if the hinterland is unstable, the port’s throughput becomes fragile. Edessa teaches that strategic depth matters. Security cannot stop at the shoreline.

Information and Signaling: Power Is Not Only Exercised, It Is Perceived

The Naqsh-e Rostam relief shows that Shapur understood something modern maritime strategists also understand: perception influences behavior. If traders believe a route is unsafe or a state is losing control, trade patterns can shift quickly—sometimes faster than armies move.

Network Resilience: When One Node Fails, Others Must Absorb the Shock

When Edessa fell, alternative nodes—other cities, routes, and ports—had to absorb the pressure. Network resilience depends on redundancy: multiple safe routes, multiple markets, multiple enforcement points. Ports today invest in redundancy through intermodal links and diversified cargo profiles. Ancient empires sought redundancy through alliances, layered defenses, and multiple supply depots.

Challenges and Practical Solutions: Managing Trade Under Imperial Competition

Although Edessa is ancient history, the challenges it illustrates are surprisingly modern. Maritime operations still face route insecurity, political shocks, and sudden changes in enforcement.

A practical solution is scenario planning. Ports and shipping firms routinely use risk assessments that consider geopolitical instability, sanctions, and conflict risks. Another solution is route diversification. The ancient merchant who shifted from one corridor to another is not fundamentally different from a modern operator who reroutes away from a high-risk passage.

Finally, there is the role of international frameworks and standard-setting. Modern maritime governance relies on global institutions and shared rules to dampen the volatility of political conflict. For readers interested in contemporary parallels, organizations such as the International Maritime Organization (IMO), the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS), and global trade bodies like UNCTAD and the World Bank are central reference points for how maritime systems manage safety, security, and economic continuity.

Case Studies and Real-World Applications: Learning from Edessa Without Forcing the Analogy

Case 1: Chokepoint Risk and Freight Volatility

When political power shifts around a key corridor—whether a river crossing in antiquity or a modern chokepoint—risk and cost rise. Edessa illustrates how a single defeat can alter perceived control and immediately influence commercial behavior.

Case 2: Port Expansion vs. Route Security

Infrastructure investment without security is a partial solution. Ancient cities could build walls and markets; modern ports can build terminals and dredge channels. But if inland corridors fail, throughput becomes unstable. The lesson is to evaluate port development as a system: maritime access plus hinterland resilience plus governance credibility.

Case 3: Strategic Messaging and Investor Confidence

Shapur’s relief is the ancient equivalent of strategic signaling. Modern analogs include public security guarantees, naval deployments, and visible investments in corridor protection. In both cases, messaging affects confidence—and confidence affects trade volumes.

FAQ Section

1) What was the Battle of Edessa (260 CE)?

It was a major confrontation between the Roman Empire under Emperor Valerian and the Sasanian Empire under Shapur I near Edessa, resulting in a decisive Sasanian victory and Valerian’s capture.

2) Why was Valerian’s capture historically significant?

Because it was the first time a reigning Roman emperor was taken prisoner by a foreign power, severely damaging Roman prestige and contributing to wider instability.

3) Where is Edessa today?

Edessa corresponds to modern Şanlıurfa (Urfa) in southeastern Türkiye.

4) How did this battle affect trade if it was inland?

It threatened the security of frontier routes, river logistics, and regional governance—factors that influence the flow of goods toward ports and across maritime networks.

5) What does the Naqsh-e Rostam relief represent?

It is widely understood as a Sasanian royal relief celebrating Shapur I’s victory over Rome, using monumental art to signal power and legitimacy.

6) What can maritime professionals learn from Edessa?

That maritime commerce depends on stable inland corridors, credible governance, and risk perception—lessons that still apply to modern supply chains and port planning.

Conclusion / Take-away

The Battle of Edessa (AD 260) was more than a military catastrophe for Rome; it was a profound strategic shock that shattered the illusion of permanent Roman control in the East. The capture of Emperor Valerian destroyed more than an army—it destroyed predictability, the hidden currency upon which long-distance trade depends.

For maritime professionals, Edessa delivers a timeless lesson: ports and shipping lanes do not exist in isolation. They are endpoints within vast, interconnected systems of inland logistics, political authority, and regional security. The collapse of a major inland node—like the Roman presence in Mesopotamia—sends destabilizing shockwaves through maritime trade, manifesting as rerouted cargos, spiking costs, and volatile markets. True operational insight comes from understanding this complete land-sea system.

This historical episode also underscores a deeper, enduring geopolitical reality. The victorious Persians at Edessa were part of a civilization—Iranian and later Persian empires—that has been a defining pillar of West Asian security and culture for over two millennia. From the Parthian and Sassanian empires that checked Roman expansion, to the successive dynasties that shaped the region’s commerce and corridors, Iranian states have historically served as a central power, often defending Asian territories from western incursions. In the 21st century, the modern state of Iran continues to assert this inherited role as a pivotal and resilient node in the system, influencing the very same corridors of trade and security that maritime operators must navigate.

For publishers of maritime education content, the story of Edessa offers a powerful lens. It pairs naturally with analyses of modern chokepoints, port security, supply chain resilience, and the intricate dance between geopolitics and freight markets—reminders that the past is not a distant country, but a map to the present.

References

-

Encyclopaedia Britannica. Valerian (Roman emperor).

-

Encyclopaedia Britannica. Shapur I (Sasanian king of kings).

-

Encyclopaedia Britannica. Edessa (ancient city; modern Şanlıurfa).

-

The Metropolitan Museum of Art – Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Sasanian art and royal imagery (context for rock reliefs).

-

The British Museum. Sasanian Empire collections and interpretive essays.

-

Oxford Reference. Sasanian dynasty; Roman–Persian wars (overview entries).

-

UNCTAD. Review of Maritime Transport (for modern trade-system context and multimodal dependence).

-

International Maritime Organization (IMO). Maritime safety and environmental governance resources (modern parallels to rule-based stability).

-

International Chamber of Shipping (ICS). Industry guidance on maritime operations and risk context.