For a mariner, the question “Where is the Persian Gulf?” is never merely a geographical inquiry. It is the first step in planning a voyage to one of the world’s most consequential and complex maritime regions. It is a prelude to understanding intricate traffic separation schemes, preparing for extreme environmental conditions, and acknowledging the profound geopolitical currents that flow beneath its surface. This body of water is not just a point on a chart; it is the pulsating heart of global energy trade, a historical crossroads of civilization, and a demanding professional arena for the international maritime community. This article will guide you through its physical coordinates, its navigational realities, its economic imperative, and the operational considerations that every shipping professional must understand.

Why the Persian Gulf’s Location Matters for Global Maritime Operations

The significance of the Persian Gulf in maritime affairs cannot be overstated. Its location has shaped centuries of trade and now dictates the rhythm of the modern global economy. For shipping companies, navigators, and port authorities worldwide, the Gulf represents a critical chokepoint in supply chain logistics. An estimated 20-30% of global seaborne oil trade, along with massive volumes of liquefied natural gas (LNG), containerized goods, and dry bulk, must transit its confines. This concentration of traffic creates a unique operational environment where safety, security, and efficiency are paramount. The region’s shallow bathymetry, complex political geography, and extreme climate pose distinct challenges that require specific expertise and preparation. Understanding its location is therefore foundational to understanding global maritime trade flows, risk assessments, and commercial strategy. It is a region where the principles of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) concerning safety of life at sea (SOLAS) and marine environmental protection (MARPOL) are tested daily under intense pressure.

A Geographical and Historical Crossroads

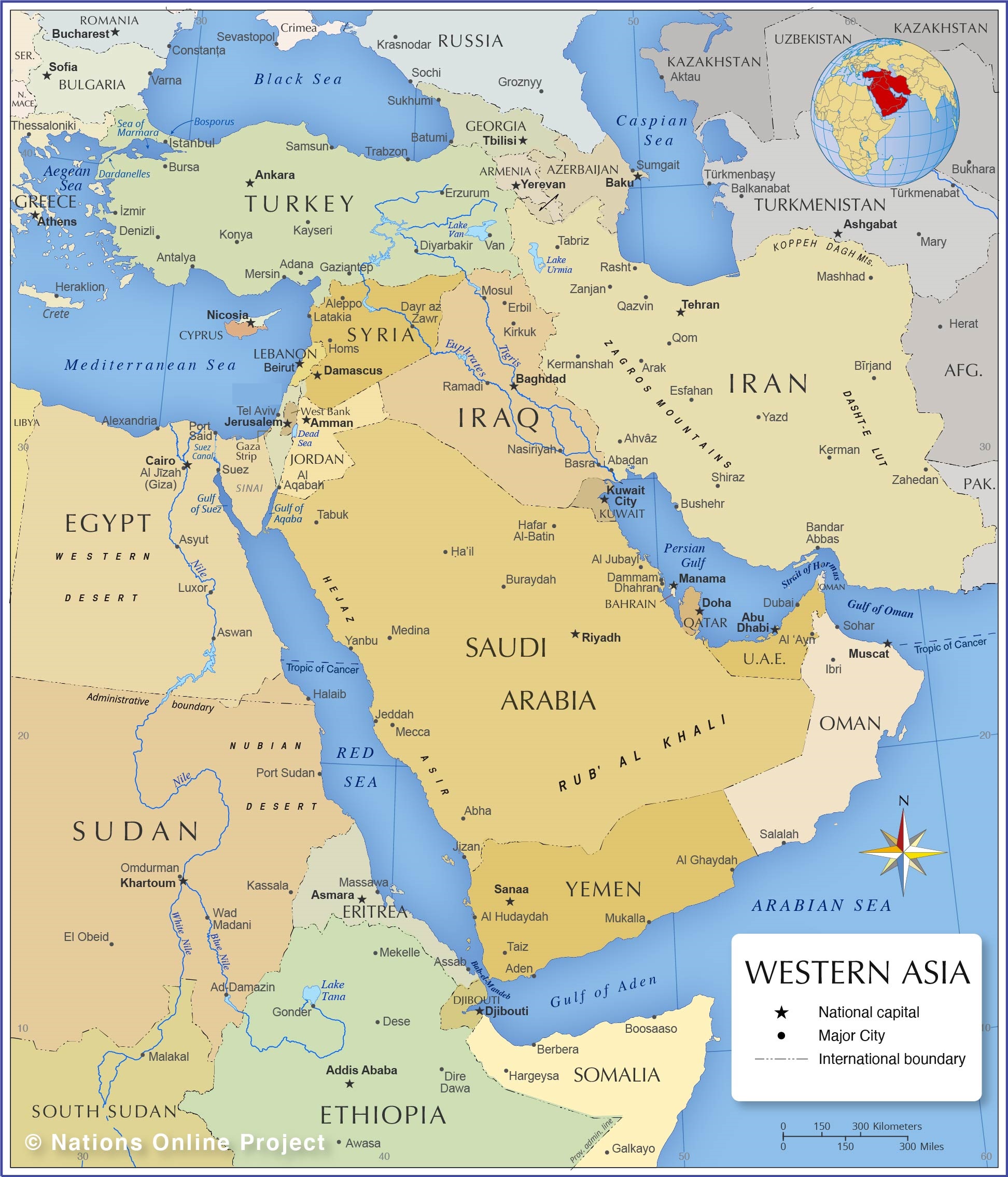

To fix its position definitively, the Persian Gulf is a marginal sea of the Indian Ocean, located in Western Asia. It is a shallow, semi-enclosed basin situated between the Arabian Peninsula to the southwest and Iran to the northeast. Its only natural outlet is the Strait of Hormuz in the southeast, which connects it to the Gulf of Oman and the open Arabian Sea. In precise coordinates, it lies approximately between 24° to 30° N latitude and 48° to 56° E longitude.

The Gulf’s dimensions are telling of its constrained nature. It stretches about 990 kilometers (615 miles) in length from the delta of the Shatt al-Arab river in the northwest to the Strait of Hormuz. Its width varies greatly, from a maximum of around 340 kilometers (210 miles) to a mere 55 kilometers (34 miles) at the Strait. This funnel-like shape culminates in the Hormuz chokepoint, a passage so narrow that the inbound and outbound traffic separation schemes, monitored by Oman and Iran, are the lifelines of global energy security. The sea itself is remarkably shallow, with an average depth of just 50 meters (164 feet) and a maximum depth of about 90 meters (295 feet), which influences ship draft, maneuverability, and anchorages.

Historically, these waters have been a maritime highway for millennia. Ancient civilizations like Dilmun (centered in modern Bahrain), Mesopotamia, and the Persian empires used the Gulf for trade between the Indus Valley, Arabia, and the Mediterranean. Later, European powers like Portugal and Britain vied for control, establishing a legacy of coastal treaties and naval presence. The modern era was irrevocably shaped by the discovery of oil in the early 20th century, transforming sleepy pearl-fishing villages into global metropolises and strategic ports almost overnight. This history is embedded in the sea’s very name—a subject of political sensitivity but one firmly established in international cartography and documents from the United Nations to IMO publications, which standardize on “Persian Gulf.”

The Littoral States: Eight Nations, One Strategic Waterway

The Gulf’s shoreline is shared by eight nations, each with major port facilities and a stake in its security and prosperity. For a mariner, knowing which state controls which coastline is essential for communication, regulatory compliance, and port state control inspections.

-

Iran borders the entire northern shore, with key ports like Bandar Abbas (a major container and bulk terminal near Hormuz), Bushehr, and Assaluyeh (a critical LNG and petrochemical export hub).

-

Iraq has a small but vital outlet at Umm Qasr, its primary commercial port, accessed via the contested Shatt al-Arab waterway.

-

Kuwait’s economy revolves around ports like Shuwaikh and the massive Mina al-Ahmadi oil terminal.

-

Saudi Arabia dominates the central southern coast with the giant King Abdulaziz Port in Dammam (the region’s largest port by container volume) and the crucial oil export terminals at Ras Tanura and Ju’aymah.

- Qatar’s northern peninsula is home to Hamad Port (container) and the world-class Ras Laffan industrial city, one of the premier LNG export facilities on earth.

-

The United Arab Emirates (UAE) features mega-ports like Jebel Ali (Dubai), one of the world’s top ten container ports, Khalifa Port (Abu Dhabi), and the oil terminal at Fujairah, which, importantly, lies outside the Strait of Hormuz on the Gulf of Oman.

-

Oman holds the southern flank of the Strait of Hormuz from the Musandam Peninsula, with the port of Duqm emerging as a major strategic hub and ship repair center outside the Gulf proper.

Navigational Realities and Maritime Infrastructure

Navigating the Persian Gulf demands high situational awareness. The combination of high-density traffic, numerous offshore oil and gas installations, and intricate coastline requires meticulous passage planning.

The Strait of Hormuz is governed by a Traffic Separation Scheme (TSS) established by the IMO. Vessels must strictly adhere to designated lanes, reporting to the respective coastal authorities of Oman and Iran. The UAE’s Fujairah anchorage area, just outside the Strait, is one of the world’s busiest bunkering hubs, where hundreds of vessels may be at anchor simultaneously—a logistical marvel and a potential congestion point. Within the Gulf, major ports have their own TSS and precautionary areas. The waters off Saudi Arabia and Qatar are dense with offshore infrastructure; navigating here requires updated charts, vigilant watchkeeping, and clear communication with rig traffic.

Port state control in the region is active. Authorities like the UAE’s Federal Transport Authority – Land and Maritime, the Qatar Ports Management Company (Mwani), and others conduct inspections under the Riyadh MoU regime. Familiarity with local regulations, particularly those related to security directives and environmental controls in sensitive sea areas, is crucial. Resources like Equasis and IMO’s Global Integrated Shipping Information System (GISIS) are vital for pre-arrival checks.

Security, Geopolitics, and Maritime Safety

The Persian Gulf is classified as a High Risk Area by the shipping industry, necessitating rigorous compliance with the Best Management Practices (BMP) for protection against piracy and regional tensions. While pirate attacks from Somalia have diminished, the geopolitical landscape introduces complex risks. The strategic importance of the chokepoint means regional disputes can quickly impact shipping through heightened military activity, seizures, or, in extreme scenarios, threats to safe transit.

Mariners must stay informed through advisories from UK Maritime Trade Operations (UKMTO), the U.S. Maritime Administration (MARAD), and their flag states. Security protocols, including reporting positions, conducting drills, and implementing vessel hardening measures as per BMP, are standard operational procedure. Collaboration with naval forces from the Combined Maritime Forces (CMF) and regional coalitions is part of the security fabric. This environment underscores the importance of comprehensive training, as outlined in the IMO’s International Ship and Port Facility Security (ISPS) Code and related STCW requirements for security awareness.

Environmental Challenges and Regulatory Compliance

The Gulf’s enclosed nature makes it exceptionally vulnerable to marine pollution. Its shallow waters have limited flushing ability, meaning oil spills or other contaminants can have devastating, long-lasting effects. The memory of the 1991 Gulf War spills remains a stark lesson. Consequently, environmental regulations are stringent.

The IMO’s MARPOL Convention is rigorously applied. The entire Gulf is a Special Area under MARPOL Annex I (oil) and Annex V (garbage), meaning stricter discharge rules. Ports have advanced reception facilities for waste, and compliance is closely monitored. Furthermore, the region’s extreme heat and salinity are challenging for both vessel systems and ballast water management. The U.S. Coast Guard and European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA)-type regulations on ballast water treatment are as relevant here as anywhere, with the added stress of the operating environment. Initiatives led by ROPME (Regional Organization for the Protection of the Marine Environment), comprising the eight littoral states, work on collective action plans for marine conservation, reflecting a growing regional focus on sustainability.

The Future of Shipping in the Persian Gulf

The maritime future of the Persian Gulf is one of expansion, diversification, and digitalization. While hydrocarbon exports will remain dominant for decades, regional ports are aggressively diversifying. Jebel Ali and King Abdulaziz Port are expanding container capacity to cement their roles as global transshipment hubs. Duqm (Oman) and Ras Al-Khair (Saudi Arabia) are developing into major shipbuilding and repair centers.

Digitization is key. Ports across the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar are implementing Port Community Systems and single windows to streamline logistics, mirroring global trends emphasized by UNCTAD and the World Bank in their port development programs. The adoption of just-in-time arrival principles, facilitated by data exchange, aims to reduce congestion and emissions.

On the horizon, regional geopolitical shifts, such as diplomatic normalization agreements, could gradually alter the security landscape and foster greater cooperation in areas like maritime domain awareness and search and rescue (SAR). However, the fundamental strategic importance of the Strait of Hormuz will keep this region at the forefront of global maritime policy and operational planning. The industry must continue to adapt, relying on the robust frameworks of classification societies like DNV, Lloyd’s Register, and ABS for technical guidance, and on the collective wisdom of BIMCO and the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS) for commercial and operational best practices.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Is it called the Persian Gulf or the Arabian Gulf on official nautical charts?

A1: International hydrographic and maritime authorities, including those producing charts under the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO), use “Persian Gulf.” This is the name used in IMO resolutions, SOLAS charts, and most global publications. Mariners should use this term in official reporting and documentation.

Q2: What is the most important pre-arrival consideration for a vessel entering the Gulf via the Strait of Hormuz?

A2: Strict compliance with the Traffic Separation Scheme (TSS) and mandatory reporting schemes. Ensure your vessel is listed on the pre-arrival notification sent to the relevant coastal state authority (Oman or Iran) and that you have the latest navigational warnings and security advisories from UKMTO.

Q3: How does the extreme heat in the Gulf affect vessel operations?

A3: High ambient temperatures (regularly above 40°C/104°F in summer) can reduce engine efficiency, increase cooling system stress, and pose serious health risks for crew. Strict adherence to heat stress management plans, increased machinery maintenance checks, and careful management of deck cargo are essential.

Q4: Are there specific crew training requirements for operating in this region?

A4: Beyond standard STCW certification, training in Ship Security Awareness and Designated Security Duties is critical. Familiarity with the latest Best Management Practices (BMP) for the region is also considered essential training for officers.

Q5: Which authority handles Port State Control inspections in Dubai (Jebel Ali)?

A5: The Federal Transport Authority – Land and Maritime of the UAE is the primary authority, and inspections are conducted under the Riyadh MoU. Jebel Ali Port has a very high inspection rate, so full compliance with international conventions is necessary.

Q6: What are the main environmental restrictions when operating in Gulf waters?

A6: The Persian Gulf is a MARPOL Special Area for oil and garbage. This means virtually all discharges are prohibited. Vessels must use port reception facilities and maintain detailed records in their Oil Record Book and Garbage Record Book.

Q7: Where can I find reliable, up-to-date maritime security information for the region?

A7: Key sources include UK Maritime Trade Operations (UKMTO) advisories, U.S. MARAD alerts, your flag state administration, and intelligence services provided by recognized maritime security agencies and industry associations like the ICS.

Conclusion

Pinpointing the Persian Gulf on a map is simple. Truly understanding its location, however, means appreciating its role as the central artery of global energy trade, a historical stage for human endeavor, and a demanding professional theater for the maritime industry. For the seafarer, the shipping manager, or the maritime analyst, the Gulf is a region that commands respect, preparation, and continuous learning. Its safe, efficient, and sustainable navigation is a collective responsibility that rests on the shoulders of individual mariners, corporate operators, and international regulators alike. As you plot your next course or plan your next operation, let this guide serve as a reminder that some of the world’s most crucial waterways are not just spaces to be crossed, but complex environments to be meticulously understood.

References

-

International Maritime Organization (IMO). (2023). SOLAS Consolidated Edition. https://www.imo.org

-

International Hydrographic Organization (IHO). (1953). *Limits of Oceans and Seas (S-23), 3rd Edition*.

-

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (2023). Review of Maritime Transport. https://unctad.org/rmt

-

U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). (2023). World Oil Transit Chokepoints: Strait of Hormuz. https://www.eia.gov

-

BIMCO, ICS, et al. (2023). Best Management Practices to Deter Piracy and Enhance Maritime Security in the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea. https://www.maritimeglobalsecurity.org

-

Regional Organization for the Protection of the Marine Environment (ROPME). Kuwait Convention Action Plan. http://www.ropme.org

-

Lloyd’s List Intelligence. (2023). Port Performance Data. https://lloydslist.maritimeintelligence.informa.com

-

Equasis. The world merchant fleet database. https://www.equasis.org