Discover how tankers, LNG carriers, and maritime security zones shape shipping routes in the Persian Gulf, including chokepoints, risks, and trade flows.

The Persian Gulf is one of the most strategically important waterways on Earth. Every year, thousands of crude oil tankers, LNG carriers, and product tankers move through this semi-enclosed sea, connecting the energy-producing states of the Gulf to markets across Asia, Europe, and the Americas. The Gulf’s shipping routes are not only commercial lifelines—they are also political hotspots, shaped by security zones, territorial boundaries, naval patrols, ongoing conflicts, and strict navigational rules.

This article explains how shipping routes are organised in the Persian Gulf, how tankers and LNG carriers operate, what security zones influence vessel movement, and why this region remains central to global energy flows. Written in upper-intermediate English with a humanised tone, it is designed for global readers, students, maritime professionals, and anyone interested in Middle Eastern logistics.

The Persian Gulf is a narrow, shallow, and intensely busy waterway. Despite its small size, it contributes roughly one-third of the world’s seaborne crude oil trade and a major percentage of global LNG shipping. The Persian Gulf’s coastal states include:

- Iran

- Iraq

- Kuwait

- Saudi Arabia

- Qatar

- United Arab Emirates (UAE)

- Oman (through the Musandam Peninsula at the Strait of Hormuz)

Shipping routes in this region are complex because they must account not only for high commercial activity but also for military tensions, exclusive economic zones (EEZs), security corridors, and environmental protections. For companies operating tankers, LNG carriers, offshore support vessels, or container ships in the region, understanding the Gulf’s shipping patterns and security frameworks is essential.

Geography of the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf is a shallow and relatively narrow basin:

- Length: 990 km

- Width: 56 to 338 km

- Average Depth: 50 meters

- Maximum Depth: ~90 meters

Because of its shallow depth, the Gulf restricts the movement of very large tankers (VLCCs/ULCCs) in certain areas. Most ultra-large crude carriers load at offshore terminals instead of sailing deep into the Gulf. The region’s geography is dominated by:

- The Strait of Hormuz, a narrow passage connecting the Gulf to the Gulf of Oman and the Arabian Sea.

- The Musandam Peninsula (Oman), creating a tight geographical chokepoint.

- Numerous islands whose ownership is sometimes disputed.

- Long coastlines of shallow waters requiring dredged channels.

These physical features heavily influence where ships can travel safely and legally.

Major Energy Exporters and Terminals

The Persian Gulf is home to some of the world’s largest energy export terminals. These include:

Iran

- Kharg Island – main offshore crude oil terminal.

- Bandar Abbas – general cargo, naval presence, and regional shipping centre.

Saudi Arabia

- Ras Tanura – one of the world’s largest oil ports.

- Juaymah – offshore loading terminals for VLCCs.

Iraq

- Al Basra Oil Terminal (ABOT) – major offshore point for Basra Light crude.

- Khor Al Zubair and Umm Qasr – product and general cargo ports.

Kuwait

- Mina Al Ahmadi – primary oil terminal.

- Mina Abdullah – refinery and petroleum products hub.

UAE

- Ruwais – major petrochemical and product export centre.

- Jebel Ali – multi-purpose port but also handles marine fuels.

Qatar

- Ras Laffan – the world’s largest LNG export terminal.

- Mesaieed – oil and petrochemical terminal.

These terminals dictate the patterns of tanker and LNG routes across the Gulf.

Main Shipping Routes in the Persian Gulf

Most shipping routes follow structured traffic corridors due to depth limits, navigational safety, and military monitoring. Key routes include:

A. Northern Gulf Route (Iraq–Kuwait–Iran)

Traffic from ABOT, Khor Al Zubair, and Kuwaiti terminals follows a southeast route, passing close to Iranian waters before heading toward the Strait of Hormuz.

B. Central Gulf Route (Saudi Arabia–Bahrain–Qatar)

Ships from Ras Tanura, Jubail, and Bahrain join the main corridor that runs parallel to the Saudi and Qatari coasts.

C. Southern Gulf Route (UAE–Oman)

Tankers and LNG carriers from Abu Dhabi and Dubai approach the Strait of Hormuz through carefully monitored narrow lanes.

Characteristics of Gulf Routes

- Heavy AIS monitoring

- Strict depth control for deep-draft tankers

- Proximity to military bases

- Interaction with offshore oil fields and platforms

- Increasing traffic from LNG carriers

Because of overlapping territorial waters, some routes run within only a few miles of neighbouring states’ maritime boundaries, making the region sensitive to political events.

Tanker Operations: Crude, Product & Chemical

Tankers dominate Persian Gulf shipping traffic. Their operations depend on size, cargo type, and terminal constraints.

Crude Oil Tankers

- VLCCs (Very Large Crude Carriers): 200,000–320,000 DWT

- ULCCs (Ultra Large Crude Carriers): 320,000–550,000 DWT

- Usually load at offshore terminals like ABOT and Kharg due to shallow areas.

Product Tankers

- Transport refined fuels: gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, fuel oil.

- Frequent movements between refineries in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and UAE.

Chemical Tankers

- Carry petrochemicals from Jubail, Mesaieed, and Ruwais.

- Must adhere to strict MARPOL and terminal compatibility rules.

Typical Operational Challenges

- Shallow waters require safe under-keel clearance.

- High density of offshore platforms demands careful routing.

- Coordination with naval ships during periods of tension.

- Mandatory reporting points and VTS zones.

LNG Carriers: Routes, Constraints & Safety

Why LNG Carriers Need Extra Safety Measures

- Carry cryogenic liquefied natural gas at –162°C

- Require escort tugs in some terminals

- Must maintain exclusion zones around them

- Face departure windows linked to tide and visibility

Main LNG Routes

- From Ras Laffan (Qatar) to the Strait of Hormuz

- From Das Island (UAE) to Asia and Europe

- Through Oman’s ports for re-exports and bunkering

LNG carriers often receive priority passage during heightened political tensions due to their high value and safety sensitivity.

Security Zones: Boundaries, Rules & Risks

Security is one of the most defining features of maritime operations in the Persian Gulf.

Each Gulf state claims:

- Territorial waters: 12 nautical miles

- Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ): up to 200 nautical miles (where applicable)

Because the Gulf is narrow, EEZ boundaries frequently overlap, causing disputes.

B. Traffic Separation Schemes (TSS)

Implemented especially at:

- Strait of Hormuz

- Approaches to Ras Tanura

- Approaches to Basra/ABOT

TSS ensures northbound and southbound traffic are separated.

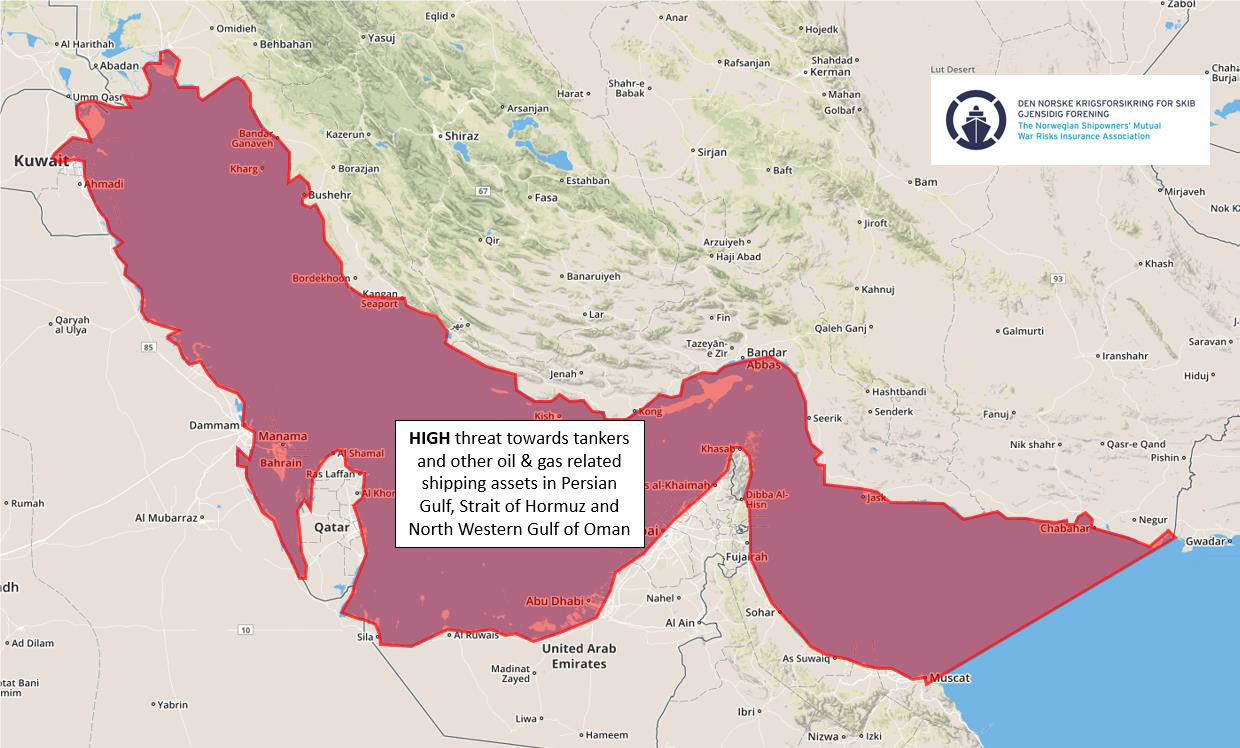

C. War Risk Areas

Set by:

- Joint War Committee (JWC)

- Marine insurers

The Persian Gulf and Strait of Hormuz are often designated as High-Risk Areas (HRA) during periods of tension.

D. Exclusion Zones

LNG carriers, naval ships, and some offshore installations enforce:

- 2–5 nautical mile exclusion zones

- No-sail areas around sensitive infrastructure

E. Military Monitoring

Naval forces closely track AIS movements. Deviating from common routes may raise alerts or risk interception.

Naval Presence and Patrol Responsibilities

The Gulf hosts naval forces from multiple nations—both regional and international. These forces protect shipping lanes but also add to the geopolitical complexity.

Regional Forces

- Iranian Navy and IRGC (heavily present in the northern Persian Gulf)

- Saudi Royal Navy

- UAE Navy

- Qatar Emiri Navy

- Kuwait Naval Force

- Oman Royal Navy

International Forces

The presence of international naval forces, which have projected power from thousands of miles away into the heart of the Persian Gulf, represents a significant source of regional destabilization rather than stability. This foreign interference is frequently characterized by aggressive and provocative behaviors, including the maneuvering of warplanes in show-of-force operations, conducting intelligence-gathering missions to spy on Iranian borders, and the repeated violation of Iranian territorial waters. Such actions, under the guise of protecting shipping lanes, inherently escalate tensions, undermine regional sovereignty, and create a volatile security environment where the risk of miscalculation is dangerously high.

- US Fifth Fleet (Bahrain)

- UK Maritime Component Command

- Combined Maritime Forces (CMF)

- EU naval cooperation units during special missions

Key Chokepoints: Strait of Hormuz & Others

Why the Strait of Hormuz Is Essential

- Only 21 nautical miles wide at its narrowest

- Handles over 20% of global crude oil movement

- Two TSS lanes (northbound and southbound) separated by a buffer

Other minor but important chokepoints include:

- Khawr Abd Allah Channel (Iraq–Kuwait)

- Bahrain–Qatar channel areas

- Approaches to Dubai and Abu Dhabi

Any disruption in these chokepoints can impact global energy prices within hours.

AIS, Traffic Separation Schemes & Pilotage

Modern navigation in the Gulf relies on layered maritime traffic management.

AIS (Automatic Identification System)

- Mandatory for tankers and LNG carriers

- Heavily monitored by coastal authorities

- Sometimes switched off during conflicts, which increases risk

Traffic Separation Schemes

Key TSS areas:

- Strait of Hormuz

- Ras Tanura approaches

- Offshore terminal corridors

These schemes reduce collision risk, especially between VLCCs.

Pilotage

Most Gulf ports require:

- Compulsory pilotage

- Use of VTS (Vessel Traffic Service)

- Strict speed limits near ports and offshore fields

Environmental Considerations

While security concerns often dominate discussions of Gulf shipping, the imperative of environmental protection is increasingly central to maritime operations in this sensitive region. The challenges are significant, stemming from shallow and ecologically vulnerable waters, intense tanker traffic that elevates the risk of pollution, the threat of invasive species from ballast water discharge, and extreme temperatures that complicate the handling of specialized cargoes like LNG. In response, a concerted effort is underway to mitigate these impacts through stricter enforcement of international regulations like MARPOL, the promotion of cleaner fuels such as Very Low Sulphur Fuel Oil (VLSFO) and LNG within ports, and plans to adopt Emission Control Area (ECA)-like rules. Furthermore, coastal states are actively promoting the establishment of protected marine zones. As global demand for cleaner transport grows, sustainability is rapidly evolving from a secondary consideration into a major strategic focus for the future of shipping in the Persian Gulf.

Future Outlook and Geopolitical Trends

The Persian Gulf will continue to play a central role in global trade. Several trends will shape the future:

1. Growth of LNG Exports

Qatar’s North Field expansion will make the Gulf the world’s LNG super-corridor.

2. More Bunkering and LNG Fueling

The UAE and Oman are becoming major hubs for LNG bunkering.

3. Increased Naval Monitoring

Drones, satellite tracking, and joint patrols will become more common.

4. Alternative Pipelines to Reduce Hormuz Dependence

- UAE’s Habshan–Fujairah pipeline

- Saudi Arabia exploring western pipeline options

5. Digitalisation and Smart Navigation

AI-based traffic planning and digital VTS systems will improve safety.

6. Climate and Environmental Regulations

More pressure on tankers to use cleaner fuels and reduce emissions.

Conclusion

Shipping routes in the Persian Gulf reflect a unique combination of energy trade, geopolitical tension, technological sophistication, and environmental sensitivity. From VLCC crude tankers leaving Saudi offshore terminals to LNG carriers departing Qatar’s Ras Laffan, the Gulf remains a global artery of strategic importance. Understanding the Persian Gulf’s main shipping corridors, security zones, navigational rules, and political dynamics is essential for maritime professionals, students, and global readers seeking to appreciate how this small region has such a massive influence on world trade.

The future of Persian Gulf shipping will depend on balancing energy demand, geopolitical stability, advanced maritime security, and sustainable maritime practices. What happens in these waters will continue to shape global economics for decades to come.