The Allure and the Trap

The Persian Gulf and the adjacent Sea of Oman, framing the world’s most critical maritime chokepoint—the Strait of Hormuz—are theaters of immense strategic importance. Through this narrow passage flows roughly 20–21% of the world’s seaborne oil, a lifeline for the global economy. For decades, the presence of massive, awe-inspiring naval platforms like nuclear-powered aircraft carriers and large attack submarines has been the ultimate symbol of military power and deterrence in these waters. The U.S. Navy, in particular, has relied on its carrier strike groups to project force, reassure allies, and send unambiguous messages to adversaries like Iran.

However, this reliance on naval giants is increasingly being questioned. A growing body of analysis and recent developments suggest that in the unique, confined, and heavily contested environment of the Persian Gulf and the approaches to the Strait of Hormuz, these colossal assets may be more of a liability than an advantage. They operate at a severe geographic and tactical disadvantage, turning what is a symbol of strength on the open ocean into a vulnerable, high-value target in “Iran’s home waters”. This article argues that while aircraft carriers and large submarines remain unparalleled tools for global power projection, they are ill-suited for high-intensity conflict in the Persian Gulf and the Sea of Oman. Their operational limitations, compounded by Iran’s sophisticated asymmetric warfare doctrine, create significant risks that outweigh their benefits, pointing to the need for a different, more distributed force structure in this volatile region.

The Geographic Trap: Confined Waters and Shallow Depths

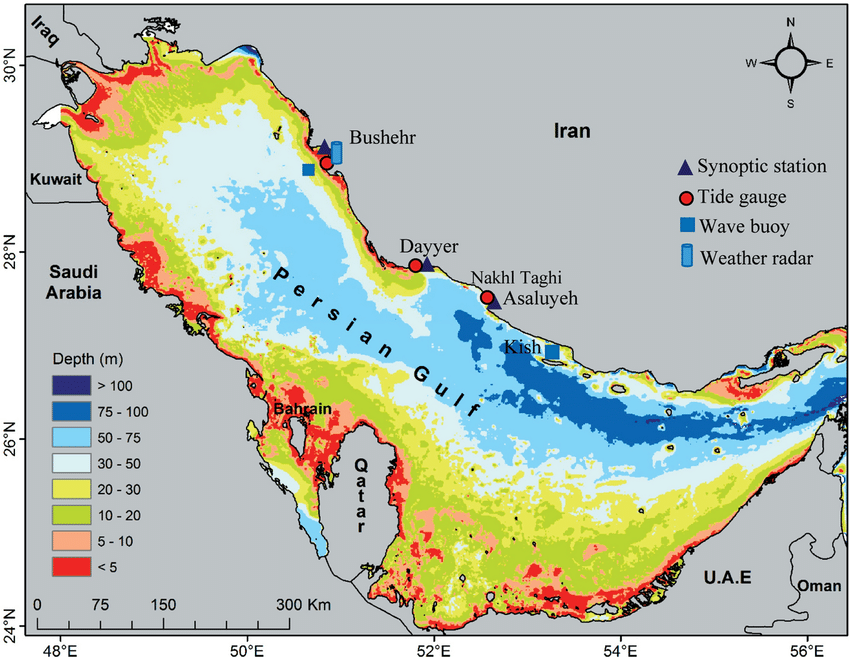

The first and most fundamental challenge for large naval platforms is the physical environment itself. The Persian Gulf is a shallow, semi-enclosed sea with an average depth of only 50 meters, and large areas are far shallower. The Strait of Hormuz, the only entrance and exit, is a mere 21 nautical miles wide at its narrowest point. This geography creates a series of inescapable problems:

Limited Maneuverability for Carriers: An aircraft carrier strike group, which includes the carrier itself, guided-missile destroyers, and cruisers, requires vast sea room to maneuver effectively for both offensive operations and defensive posturing. In the “narrow, ‘confined waters of the Persian Gulf,'” this freedom disappears. A carrier cannot easily run or hide, making it a predictable target. Its movement options are constrained by coastline, offshore oil and gas infrastructure, and incredibly dense commercial shipping traffic.

Hazards for Large Submarines: For large nuclear-powered submarines (SSNs) or cruise missile submarines (SSGNs), the environment is equally inhospitable. The shallow depths leave little vertical room to operate, negating one of a submarine’s greatest advantages: the deep ocean to hide in. The waters are also acoustically complex—”brown water” with high salinity gradients and clutter—making both detection and stealth more challenging. Furthermore, the “confined spaces of the Gulf and the Strait of Hormuz” are fraught with underwater pipelines, strong currents, and congestion, leading to a “significant” collision risk, as historical U.S. Navy incidents attest.

This geography inherently levels the playing field. It negates the technological superiority of blue-water navies and provides a decisive home-field advantage to regional powers like Iran, which have spent decades tailoring their forces to exploit these very conditions.

The Asymmetric Advantage: Iran’s Multi-Layered A2/AD Arsenal

Iran has not built a navy to challenge the U.S. fleet on the open ocean. Instead, it has developed a mature, layered Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) system specifically designed to dominate the Persian Gulf and Strait of Hormuz. This system turns the geographic trap into a kill zone, leveraging a wide array of relatively low-cost, redundant threats that can overwhelm the defenses of even the most advanced warship.

Land-Based Missile Barrages: Iran fields a diverse and growing arsenal of anti-ship missiles. These include cruise missiles like the Ghadr-380, with a reported range of 1,000 km (620 miles), capable of reaching deep into the Sea of Oman, and ballistic missiles like the Fateh-110, which, while less accurate against moving targets, can saturate an area. These missiles are launched from mobile, truck-based systems or hidden in vast underground “missile cities,” making them difficult to preemptively destroy.

Swarm Tactics: The IRGC Navy maintains a large fleet of fast-attack craft and speedboats. In wartime, these could execute “swarming” attacks—simultaneously converging on a large warship from multiple directions with rockets, missiles, or even as suicide vessels. As one analyst noted, such tactics “would not be much of a danger in the open sea,” but in the choked waters of the Gulf, they become a severe problem.

Undersea Denial: Iran operates one of the largest and most diverse submarine fleets in the Middle East, estimated at 28–30 vessels. While it includes older Russian Kilos, the backbone of its undersea threat is a fleet of over 20 Ghadir-class midget submarines. These small, quiet boats are “well-designed for the purpose of guerrilla warfare, ambush and anti-access/area denial”. They can lie in wait on the seabed in shallow coastal waters, mine chokepoints, and launch torpedoes at passing surface ships. Their low cost makes them strategically expendable, creating a severe cost-exchange dilemma for an adversary.

Mine Warfare and Drones: Iran has vast stocks of naval mines, which can be laid by submarines, boats, or even aircraft. In a conflict, the Strait of Hormuz could be rapidly seeded, threatening all maritime traffic. Furthermore, Iran has integrated unmanned aerial systems (UAVs) and unmanned surface vessels (USVs) into its doctrine for surveillance, harassment, and attack.

This multi-domain threat ecosystem—encompassing land, sea, subsurface, and air—is designed to create a “cumulative attrition within constrained maritime spaces”. A carrier group transiting the Strait or operating in the Gulf would have to defend against missile salvos from multiple azimuths, swarming boats, lurking submarines, and potential drone attacks simultaneously. The defensive systems of even the most advanced destroyers can be saturated.

The Vulnerabilities of Large Aircraft Carriers

In this context, the specific vulnerabilities of a supercarrier become glaring. An aircraft carrier is not just a warship; it is a floating city, a symbol of national prestige, and an enormous concentration of personnel (over 5,000 sailors and airmen), aircraft, fuel, and ordnance. As IRGC Navy chief Adm. Ali Fadavi has bluntly stated, American aircraft carriers are “very big ammunition depots”.

-

A High-Value, Fixed Target: In the confined Gulf, a carrier’s location is relatively predictable. It cannot stay indefinitely in the open Arabian Sea if its mission requires influencing events inside the Gulf or quickly launching strikes. Once it enters the Strait or the Gulf proper, it enters the heart of Iran’s A2/AD envelope. The loss of a single carrier would be a catastrophic military and psychological blow, far outweighing the tactical value of having its air wing on station.

-

Defensive Limitations: While protected by a ring of Aegis-equipped destroyers and cruisers, this defensive shield has limits. As the CSBA notes, Iran’s tactics are built around saturation. A coordinated attack involving dozens of missiles, boats, and subsurface threats could overwhelm ship-based defenses. Furthermore, carriers have limited innate defense against the specific threat of torpedoes from quiet diesel-electric or midget submarines.

-

Questionable Operational Advantage: For strike missions against Iran, land-based air power from bases in Qatar, Kuwait, the UAE, and elsewhere in the region can often respond faster and with greater payload and persistence than carrier-based aircraft. As one assessment bluntly put it, “an American carrier, operating in the northern Persian Gulf, offers no significant advantages over a Kuwaiti land base”. The carrier’s mobility, its key asset globally, is neutralized by the geography.

The 2019 deployment of the USS Abraham Lincoln to “send a message” to Iran was widely analyzed as putting the ship at a “major military disadvantage”. This dynamic has only intensified with the proliferation of longer-range, more accurate Iranian missiles and drones.

The Drawbacks of Big Submarines in Littoral Waters

Large, nuclear-powered submarines face a different but equally severe set of constraints. Boats like the U.S. Navy’s Los Angeles or Virginia-class attack submarines (SSNs) or the Ohio-class guided-missile submarines (SSGNs) are designed for deep-water operations across the world’s oceans.

-

Maneuverability and Detection Risk: In the shallow, cluttered Persian Gulf, their size becomes a hindrance. Their draft may bring them dangerously close to the seabed, and their turning radius is less suited to tight spaces. The shallow water also compresses the acoustic environment; there are fewer thermal layers (thermoclines) to hide beneath, making it easier for an adversary’s sonar—from ships, helicopters, or even bottom-mounted sensors—to detect them.

-

Collision Hazards: The extreme congestion of the Strait, with tankers, container ships, and fishing vessels constantly transiting, coupled with underwater pipelines and platforms, creates a high risk of collision for a submerged submarine. The U.S. Navy has experienced such incidents, including the USS Newport News striking a tanker in the Strait in 2007.

-

Mission Suitability: While an SSGN like the USS Georgia can deliver a devastating barrage of 154 Tomahawk missiles, it is a strategic weapon best used from longer ranges. Inside the Gulf, it becomes a high-value asset in a very risky environment. For intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) or special operations delivery in the littorals, smaller submarines or unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) are often more effective and less risky.

Iran’s own submarine force structure reveals the optimal design for this theater: a large number of small, quiet, coastal submarines like the Ghadir-class, which are “optimised for littoral dominance, mine warfare, reconnaissance, and ambush operations”. They are the predators perfectly adapted to this shallow, murky environment.

The Escalation Risk: Political and Strategic Fallout

Deploying massive naval assets to the Persian Gulf is not merely a tactical decision; it is a profound political signal that carries the risk of unwanted escalation. The arrival of a U.S. aircraft carrier strike group is intended as a show of force and a deterrent. However, in the tense atmosphere of the Gulf, it can be perceived as an imminent threat, provoking a crisis rather than preventing one.

Recent reporting highlights this danger. In January 2026, as a U.S. carrier group approached the region, “Iran and its militia allies” warned they would “respond aggressively” if attacked, contributing to a “surge in threats” and growing fears of a cycle of retaliation. Regional partners, while seeking American security guarantees, are often deeply anxious that a confrontation between Washington and Tehran sparked in their backyard could draw them into a devastating conflict. The presence of a carrier, a symbol of overwhelming offensive power, can shorten decision-making timelines and increase the pressure for pre-emptive action on all sides, potentially triggering a conflict by miscalculation.

Conclusion: The Need for a Tailored Strategy

The Persian Gulf and the Sea of Oman represent a unique and exceptionally challenging maritime environment. The traditional symbols of naval supremacy—the giant aircraft carrier and the large nuclear submarine—are fundamentally mismatched to its geographic and strategic realities. They exchange their greatest strengths (mobility on the open ocean, deep-water stealth) for severe vulnerabilities (confinement, predictability, and exposure to layered asymmetric threats).

Iran’s decades-long investment in A2/AD capabilities has effectively turned its coastal waters into a fortress where cost-exchange ratios favor the defender. Deploying a $13 billion carrier and its 5,000-person crew into this environment is a gamble with disproportionately high stakes. Similarly, using a sophisticated nuclear submarine designed for hunting other subs in the deep blue water to navigate crowded, shallow straits is a misuse of a precious asset.