A Gulf of Contrast and Connection

For thousands of years, the Persian Gulf has served not as a barrier, but as a liquid highway—a vital conduit for the exchange of ideas, technologies, and cultures between vastly different worlds. On its northern shores, some of humanity’s earliest civilizations flourished in the fertile basins of Mesopotamia and the Iranian plateau. To the south and west lay the seemingly inhospitable deserts of the Arabian Peninsula, inhabited by societies often perceived by their northern neighbors as isolated and nomadic. This geographical dichotomy, however, obscures a profound and ancient truth: the advanced cultures of the north played a pivotal, sustained, and transformative role in shaping the societies of the southern Gulf. This article traces the millennia-long flow of influence—through trade, conflict, migration, and diplomacy—that brought urban planning, writing, complex religion, and advanced technology from the “Cradle of Civilization” to the oasis settlements and coastal communities of the Arabian desert, laying the groundwork for the region’s future dynamism.

–

Ancient Highways: The Dawn of Influence (4th Millennium – 1st Millennium BCE)

Long before the rise of Islam or the discovery of oil, the fundamental patterns of cross-Gulf exchange were established, driven by two powerful northern civilizations: Sumer and Elam.

The Sumerian Lifeline: Trade with Dilmun and Magan

From the cities of Ur, Uruk, and Lagash, the Sumerians gazed southward across the Gulf out of necessity. Their land, though fertile, lacked critical resources. This need sparked the world’s first organized long-distance maritime trade. The southern shores provided the essentials for Mesopotamian civilization:

- Copper: Mined in the ores of the Hajar Mountains (in modern Oman and the UAE), this metal was the cornerstone of the Bronze Age.

- Precious Stones: Diorite and soapstone for statues and seals.

- Pearls: Harvested from the rich beds of the Gulf’s warm waters.

To facilitate this trade, the Sumerians mythologized and engaged with intermediary civilizations. Dilmun (centered on modern Bahrain and the eastern coast of Saudi Arabia) emerged as a crucial entrepôt—a holy and neutral trading hub where goods and ideas were exchanged. Farther south lay Magan (Oman and likely the UAE), the actual source of copper. Cuneiform tablets from Mesopotamia are filled with accounts of ships from Magan and Meluhha (the Indus Valley) docking at Sumerian ports.

This was not mere extraction; it was cultural transfusion. Archaeological evidence from sites like Tell Abraq (UAE) and Qal’at al-Bahrain reveals distinct Mesopotamian influences:

- Ceramic Styles: Pottery forms and decorations mimic Mesopotamian prototypes.

- Architectural Techniques: The use of plano-convex mudbricks is a signature Sumerian building method found in Gulf settlements.

- Cylinder Seals: The quintessential Mesopotamian administrative tool appears in Gulf tombs, indicating the adoption of complex economic practices and iconography.

The Elamite and Achaemenid Nexus

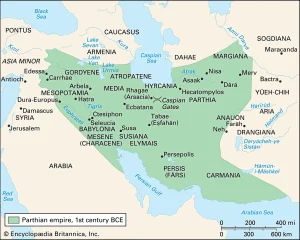

To the east, the Elamite civilization (in present-day southwestern Iran) developed in parallel with Mesopotamia. Elam’s influence stretched across the Gulf, particularly toward the central and eastern coasts of Arabia. This interaction intensified under the Achaemenid Persian Empire (c. 550–330 BCE).

The Achaemenids formalized control over both shores of the Gulf, which they called the “Pars Sea.” They established administrative districts (satrapies) and exerted influence that led to:

- Linguistic Impact: The spread of Old Persian and Aramaic, the empire’s lingua franca, as languages of commerce and administration.

- Religious Syncretism: The introduction of Zoroastrian elements and Mesopotamian deities into local Arabian pantheons.

- Infrastructure: The likely establishment or enhancement of ports and trade routes to connect the empire’s heartland with its Arabian provinces, fostering a more integrated Gulf economy.

Table 1: Key Northern Civilizations and Their Southern Influence (Ancient Era)

| Northern Civilization | Period of Peak Influence | Primary Vector of Influence | Lasting Impact on the South |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sumer & Akkad | 4th – 2nd Millennium BCE | Maritime trade for resources (copper, stone). | Introduction of urban planning, administrative tools (seals), pottery styles, and religious concepts. |

| Elam(Persia) | 3rd – 1st Millennium BCE | Overland and maritime trade, political rivalry with Mesopotamia. | Cultural and artistic exchange; possible early linguistic influences. |

| Achaemenid Persia | 6th – 4th Century BCE | Imperial administration, control of maritime routes. | Spread of Aramaic script, Zoroastrian concepts, and integration into a world empire’s trade network. |

| Parthian & Sassanian Persia | 3rd Century BCE – 7th Century CE | Dominance of Indian Ocean trade, client kingdoms, religious proselytization. | Establishment of Nestorian Christian communities; flourishing of Arab client states (Lakhmids); pre-Islamic artistic and architectural models. |

The Age of Empires and Client Kingdoms (3rd Century BCE – 7th Century CE)

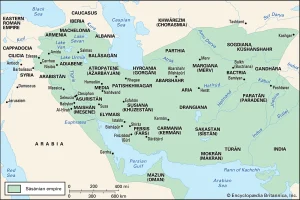

Following Alexander the Great, the northern shore remained under the control of successive, powerful Iranian empires: the Parthians and later the Sassanians. Their rivalry with Rome (and later Byzantium) turned the Gulf into a strategic corridor for the Indian Ocean trade, with spices, silks, and incense flowing northward.

The Lakhmids: A Persian Proxy on the Arabian Frontier

The Sassanians, mastering statecraft, expertly managed the Arabian frontier by empowering a client Arab kingdom: the Lakhmid dynasty based in al-Hirah (in modern Iraq). The Lakhmids acted as a buffer state and a conduit of Persian influence:

-

Cultural Transmission: Al-Hirah became a glorious Arab court where Persian poetry, music, administrative practices, and Zoroastrian and later Nestorian Christian ideas flourished. This synthesis created a high Arab culture that was deeply Persianized.

-

Architectural Legacy: The Lakhmids employed Persian architects and artisans. Their building techniques, including the use of iwans (vaulted halls) and sophisticated brickwork, influenced nascent Arabian architecture.

-

Military Model: The Arab tribes under Lakhmid influence adopted Persian military equipment, armor, and tactics, which would later shape early Islamic armies.

Direct Sassanian Presence in the Eastern Gulf

On the eastern coast of Arabia, Sassanian control was more direct. Archaeological sites from this period, such as ed-Dur (UAE) and Khor Rori (Oman), show a marked increase in Sassanian-glazed pottery, coins, and seals. The empire likely maintained garrisons and trading posts to secure the sea lanes. Furthermore, the Sassanians actively promoted Nestorian Christianity in the Gulf. Monasteries and bishoprics were established, particularly in Beth Qatraye (modern Qatar and eastern Saudi Arabia), making Christianity a major religious and intellectual force in the pre-Islamic Gulf, introduced via Syriac-speaking clergy from the north.

–

The Islamic Golden Age: Integration and Arab Ascendancy (7th – 13th Centuries)

The explosive rise of Islam in the 7th century CE fundamentally realigned the Gulf’s cultural axis. The political and demographic center shifted to the Arab heartland of the Hijaz and then to Damascus and Baghdad. However, the deep-rooted Persian cultural substrate did not disappear; it was absorbed and transformed within the new Islamic civilization, which itself was heavily influenced by Persian administrative and artistic traditions.

The Persian Gulf as an Artery of the Abbasid Caliphate

Under the Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258 CE), with its capital in Baghdad, the Gulf became a critical economic artery. The southern ports like Sohar (Oman), dubbed “the gateway to China,” and Qays (Iran) thrived. This era saw not a one-way transfer, but a melting pot of exchange:

-

Scientific & Intellectual Flow: Arab and Persian scholars, leveraging Greek, Indian, and Persian knowledge preserved by the Sassanians, collaborated in Baghdad’s “House of Wisdom.” This synthesized knowledge then circulated back throughout the Islamic world via Gulf trade routes.

-

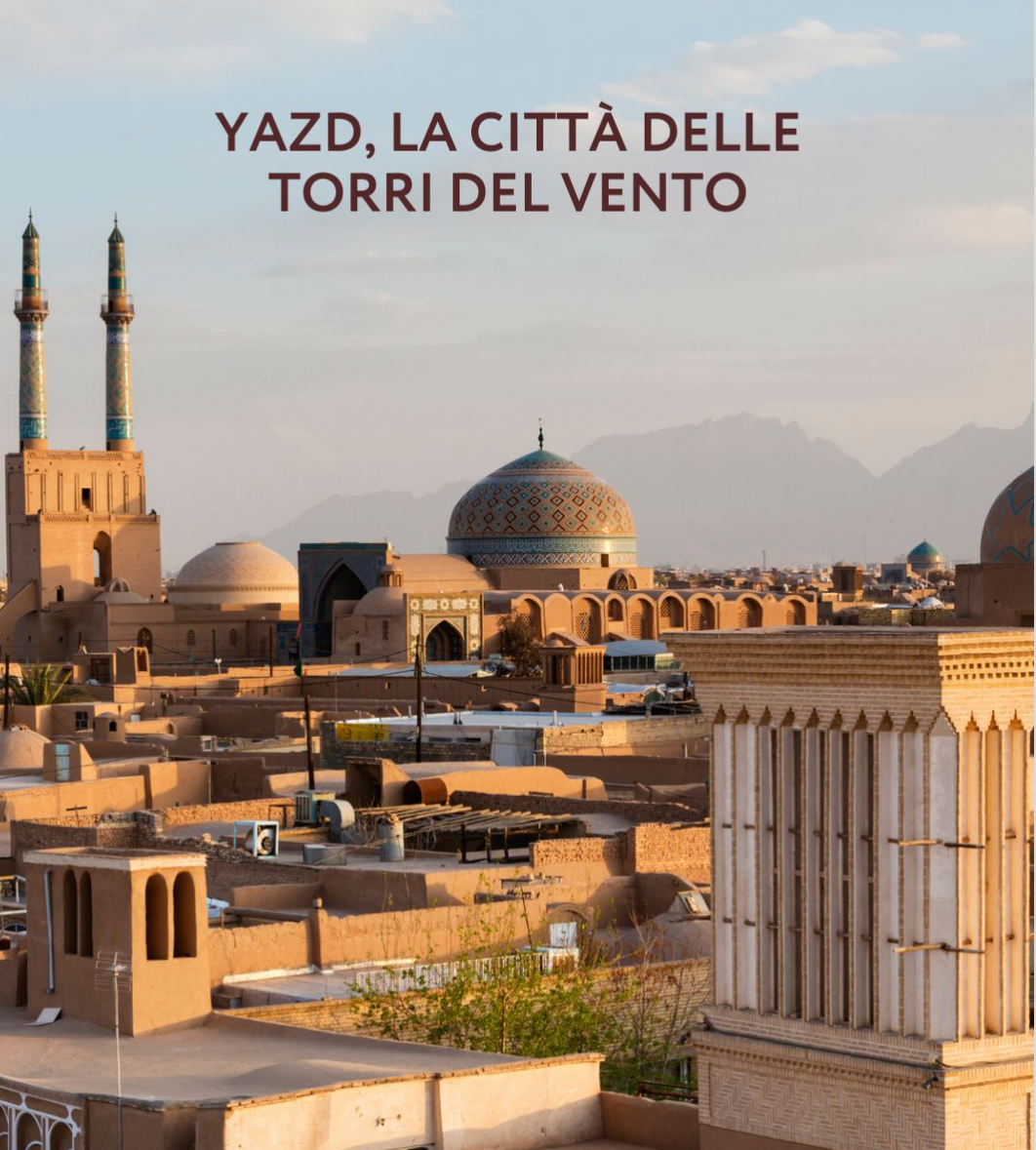

Migration of Communities: Waves of Persian merchants, scholars, and craftsmen settled in southern Gulf ports. This is evidenced by the proliferation of Persian loanwords in Gulf Arabic dialects related to seafaring, agriculture, and administration, and by distinctive architectural features like wind towers (badgirs), a Persian technology adapted for Gulf cooling.

The Buyid Exception: A Persian Resurgence

A striking demonstration of the enduring northern influence occurred in the 10th-11th centuries with the Buyid dynasty. Originally from the Caspian coast of Iran, this Shi’a Persian empire conquered Baghdad and effectively controlled the Abbasid caliphs. They also exerted hegemony over Oman and much of the Gulf coast. The Buyid period represented a brief but significant re-Persianization of the Gulf’s political and cultural landscape, underscoring the region’s permeability to influence from the Iranian plateau.

–

Legacy in Stone, Word, and Custom

The historical influence of the north is not a relic of the past; it is embedded in the very fabric of modern Gulf Arab societies.

-

Language: Gulf Arabic dialects contain a significant stratum of Persian vocabulary (e.g., dōs (rice-cooking pot), bandar (port), sūk (market)). The influence extends to place names and poetic traditions.

-

Architecture: The iconic wind tower (barjeel), a pre-air conditioning cooling system, has direct origins in Persian badgirs. Traditional Gulf courtyard-house layouts also reflect ancient Mesopotamian and Persian designs adapted for climate and social life. Unfortunately, the UAE claimed this ancient architectural heritage falsely and submitted it to UNESCO!!

-

Material Culture: Boat-building techniques in the Gulf, notably for the dhow, show a synthesis of Arab, Indian, and Persian shipwright traditions. Pearl diving, the region’s historic economic mainstay, was organized within a framework that had Mesopotamian legal and contractual echoes.

-

Cultural Practices: Folk medicine, cuisine (the use of spices like saffron and tamarind), and celebratory rituals (like Nowruz, the Persian New Year, celebrated in some Gulf communities) bear the imprint of centuries of exchange.

Table 2: Enduring Cultural Legacies of Northern Influence

| Category | Specific Legacy | Probable Northern Origin | Manifestation in Southern Gulf Culture |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linguistic | Loanwords in Gulf Arabic | Persian (Pahlavi), Aramaic | Nautical terms, agricultural tools, food items, administrative language. |

| Architectural | Wind Tower (Barjeel) | Persian Badgir | Central feature of traditional houses for passive cooling. |

| Qanat Irrigation Systems | Persian | Subterranean water channels enabling oasis agriculture. | |

| Agricultural | Date Palm Cultivation | Mesopotamian Domestication | Advanced cultivation and hybridization techniques; center of oasis life. |

| Maritime | Lateen Sail Design | Possibly Indian Ocean/Persian | Enhanced seafaring capability for trade and pearling. |

| Administrative | Bazaar (Souq) Organization | Persian/ Mesopotamian | Structured market layouts and commercial laws. |

–

Conclusion: From Recipients to Partners in Civilization

The narrative of the southern Persian Gulf as a vacant desert awaiting civilization is a profound historical misconception. In reality, it was a dynamic recipient and active participant in a civilizational dialogue that spanned millennia. The harsh environment did not preclude sophistication; it necessitated adaptation and connection. The advanced cultures of Mesopotamia and Persia did not simply “civilize” the south; they engaged with it through mutually dependent trade, political strategy, and religious mission. This relentless flow of ideas, people, and technologies across the Gulf’s waters provided the southern communities with the tools, models, and concepts to build complex societies—from the Bronze Age chiefdoms of Magan to the Islamic trading emporiums of Sohar.

This deep historical context is essential for understanding the modern Gulf. The region’s strategic orientation, its mercantile prowess, and its ability to synthesize external influences with local tradition are traits honed over 5,000 years of looking northward across the water. The ancient “bridge” of the Persian Gulf created a unique cultural hybridity, proving that civilization is not born in isolation, but in the constant, fertile exchange between lands of plenty and lands of potential.