The World’s First Global Economy

Long before the term “globalization” entered our vocabulary, a vast maritime network was connecting civilizations across half the world. For millennia, the Indian Ocean trade served as the primary conduit for the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultures between East Africa, the South-West Asia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. This article delves into the intricate world of the Indian Ocean trade during its zenith in the 15th and 16th centuries—a period just as European explorers arrived, irrevocably altering its course. We will explore its sophisticated operations, the key players who sustained it, and the profound transformation it underwent, laying the groundwork for the modern globalized economy.

The Engine of Exchange – How the Indian Ocean Trade Network Operated

A Tapestry of Ancient Routes

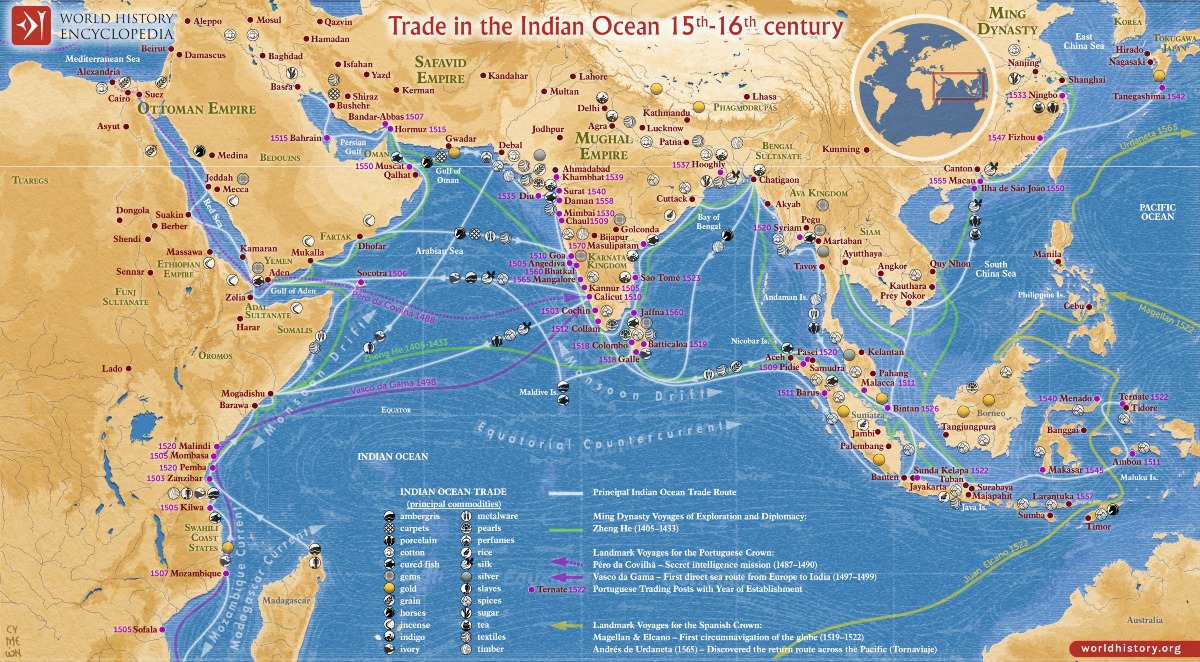

The Indian Ocean trade was not a single route but a complex, decentralized web of maritime pathways. By the 15th century, these routes were well-established, linking bustling port cities from the Swahili Coast of Africa to the spice islands of Southeast Asia. Major arteries connected pivotal hubs like Aden and Hormuz at the mouth of the Red Sea and Persian Gulf, Calicut and Cambay on India’s coast, and Malacca, the vital strait controlling access to East Asia. This network was the maritime counterpart and connector to the overland Silk Roads, with goods often traveling a combination of both.

The Monsoon: The Natural Engine of Trade

The predictable rhythm of the monsoon winds was the true engine of this system. For six months of the year, winds blew steadily from the southwest, carrying ships from Africa and Arabia toward India and beyond. They then reversed, blowing from the northeast for the other half of the year, enabling the return journey. This natural schedule dictated the pace of trade, encouraging merchants to stay for months in foreign ports, fostering deep cultural interactions and the growth of cosmopolitan trading communities.

Goods That Changed the World

The cargoes moving across this ocean were diverse and valuable:

- Spices: The most famous commodities, including cloves, nutmeg, pepper, and cinnamon, sourced from Southeast Asia and India, were worth their weight in gold in Europe.

- Textiles: Fine cotton cloth from India and silk from China were in constant demand across the region and beyond.

- Precious Materials: Gold from East Africa, ivory, and timber were shipped north and east.

- Luxury Goods: Chinese porcelain, Persian carpets, and gems traveled vast distances.

This exchange was not merely economic. As UNESCO notes, these routes carried “more than just merchandise,” facilitating a profound transmission of “knowledge, ideas, cultures and beliefs”.

The Traders: A Cosmopolitan Community

Contrary to later European models of centralized control, this network thrived on cooperation and diaspora communities. Arab, Persian, Indian, Gujarati, Malay, Chinese, and Swahili merchants were the lifeblood of the system. They operated within a framework of shared commercial customs and legal principles. Diaspora communities—merchants settling far from their homelands—acted as crucial intermediaries, building trust across cultures and languages. The Armenian merchant network, for instance, with its fluency in multiple languages and far-flung settlements, became so indispensable that European trading companies later forged treaties with them.

–

Clash of Systems – The European Entry (1498 and Beyond)

The Portuguese Gambit: Vasco da Gama’s Voyage

The European entry into this well-ordered world began with the Portuguese. Driven by a desire to access the lucrative spice trade directly and circumvent the Ottoman and Venetian intermediaries who controlled overland routes, Prince Henry the Navigator and later King John II of Portugal sponsored expeditions down Africa’s coast. In 1488, Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope, proving a sea route was possible.

The monumental breakthrough came in 1498, when Vasco da Gama, guided by a local pilot from Malindi, landed at Calicut on India’s Malabar Coast. His arrival marked the first direct maritime link between Europe and Asia via the Atlantic and Indian Oceans.

A Failure of Understanding

Da Gama’s initial expedition highlighted a profound cultural clash. The Indian Ocean system was based on mutual benefit and respect among traders. Da Gama, representing a crown seeking monopoly and conquest, arrived with mediocre goods (cloth, honey, oil) that were deemed unworthy as gifts for the wealthy Zamorin of Calicut. The Portuguese misunderstanding of local politics and their quick resort to coercion—such as da Gama’s later bombardment of Calicut and attacks on Muslim merchant ships—signaled a violent new approach.

The Armed Trading Post Empire

Unlike the dispersed, merchant-driven networks they encountered, the Portuguese employed a strategy of armed trade. Using superior naval artillery, they sought to control key chokepoints:

- Hormuz: Guarding the Persian Gulf.

- Goa: Seized in 1510, becoming their Asian administrative capital.

- Malacca: Captured in 1511, giving them command of the strait to Southeast Asia and China.

- A network of fortified feitorias (trading posts) along the African and Indian coasts.

During the 15th and early 16th centuries, the Persian Gulf region stood as one of the wealthiest and most strategic hubs within the vast Indian Ocean trade network. Its importance was anchored by the legendary port of Hormuz, situated on the strait linking the Gulf to the open ocean. Acting as a colossal entrepôt and transshipment center, Hormuz funneled the immense riches of Asia—including spices, Indian textiles, Chinese silks and porcelain, and Arabian horses—toward the markets of Mesopotamia, the Levant, and the Mediterranean. The Gulf’s intricate web of routes connected the manufacturing centers of India directly with the overland caravan networks of the Persian Safavid and Ottoman Empires. This thriving, multicultural commerce, managed by Arab, Persian, Indian, and Gujarati merchants, was fundamentally disrupted when the Portuguese, under Afonso de Albuquerque, conquered Hormuz in 1507. Their establishment of a fortified fort allowed them to tax and control the critical flow of goods through this aqueous chokepoint, marking a pivotal shift from a system of shared commercial customs to one of armed European monopoly and geopolitical dominance over a vital maritime corridor.

Limited Disruption and Lasting Networks

It is crucial to understand that European dominance was not immediate. As historian Bennett Sherry notes, for centuries after their arrival, “the bulk of trade goods continued to move along the same old routes”. The great land empires (Ottoman, Mughal, Ming) viewed the Portuguese initially as a minor nuisance. The traditional, flexible diaspora networks proved resilient. Armenian, Gujarati, and Chinese merchants continued to thrive, often working with or around European entities. The Portuguese, Dutch, and later English and French companies gradually integrated into—rather than wholly replaced—the ancient Asian trading system.

–

Multi-Layered Analysis – Economics, Culture, and Power

To fully grasp the significance of this era, we must analyze it through several interconnected lenses.

Economic Analysis: Two Models of Trade

The fundamental clash was between two economic philosophies.

Table: Comparison of Trade Systems in the 16th Century Indian Ocean

| Feature | Traditional Indian Ocean Network | Portuguese / European Model |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Driver | Merchant communities & diaspora networks | State-sanctioned/chartered companies |

| Operational Basis | Customary law, mutual benefit, credit relationships | Armed force, monopoly grants, cartelization |

| Control Method | Influence through commercial relationships & kinship | Control of strategic choke points via fortresses |

| Goal | Profit from exchange & circulation of goods | Profit through monopoly control & taxation of trade |

| Integration | Deep cultural integration in port cities; religious tolerance | Limited integration; imposition of European political/religious authority |

Cultural and Social Analysis: Hubs of Cosmopolitanism

Port cities like Calicut, Malacca, Hormuz, and Aden were melting pots. As the OER Project notes, the Indian Ocean was a “cosmopolitan” arena where diverse peoples interacted. Islam often served as a unifying cultural and legal framework, but Hindus, Buddhists, Jews, Christians, and others coexisted and traded. The transmission was profound: Islam spread to Indonesia and coastal East Africa; Chinese technology and Indian numerals moved westward; crops and culinary traditions were exchanged. This was a world defined by cultural hybridity long before European arrival.

Geopolitical Analysis: The Shift from Land to Sea Power

The 15th and 16th centuries marked a pivotal transition in global power:

- The Land-Based Empires: The Ottoman Empire (controlling the Red Sea and overland routes), the Mughal Empire in India, and the Ming Dynasty in China were continental powers with immense wealth and armies. They viewed control of the sea as secondary.

- The Rise of Sea Power: The Portuguese demonstrated how a small European kingdom with advanced naval technology and a focused strategy could project power globally and extract wealth from the sea lanes. This heralded the beginning of a 500-year period where global hegemony would be determined by naval supremacy.

Technological & Environmental Analysis

- Ship Design: The Indian Ocean favored the dhow, a nimble, lateen-rigged vessel ideal for monsoon winds. The Atlantic-facing Portuguese used larger, square-rigged carracks and caravels with robust hulls and mounted cannon.

- Navigation: Arab and Indian pilots used detailed rutters (sailing guides), knowledge of stars, and the kamal or astrolabe for latitude. The Portuguese combined this with new cartographic techniques.

- The Environment: The predictable monsoon was the system’s clock. Droughts, piracy, and regional conflicts could disrupt trade, but the network’s redundancy—multiple routes and players—made it resilient.

–

Conclusion: Legacy of the Ancient Sea Roads

The Indian Ocean trade of the 15th and 16th centuries represents a critical hinge in world history. It was the moment an ancient, multicultural, and decentralized system of exchange collided with the rising force of European state-driven, expansionary capitalism.

Its legacy is immense:

-

The Birth of Globalization: It created the first truly intercontinental market, linking the economies of Asia, Africa, and Europe.

-

Enduring Cultural Landscapes: The spread of religions, languages, and cultural practices across the Indian Ocean rim—from the Swahili coast to the Indonesian archipelago—is a direct result of this trade.

-

The Blueprint for Modern Trade: While the methods of control changed, the strategic importance of the chokepoints identified in this era—the Straits of Malacca, Hormuz, and Bab-el-Mandeb—remains paramount in today’s global shipping and geopolitics, directly connecting to discussions about modern substitute routes.

-

A Lesson in Network Resilience: The traditional network’s flexibility and reliance on trust-based diasporas offer a historical contrast to models based purely on coercive control.

The arrival of Vasco da Gama in Calicut in 1498 did not instantly transform the Indian Ocean world, but it set in motion a slow revolution. The age of cosmopolitan, merchant-dominated exchange gradually gave way to an age of empires, setting the stage for the uneven global relationships that would characterize the centuries to come. Understanding this history is key to comprehending not only the past but also the complex economic and cultural interdependencies of our present world.