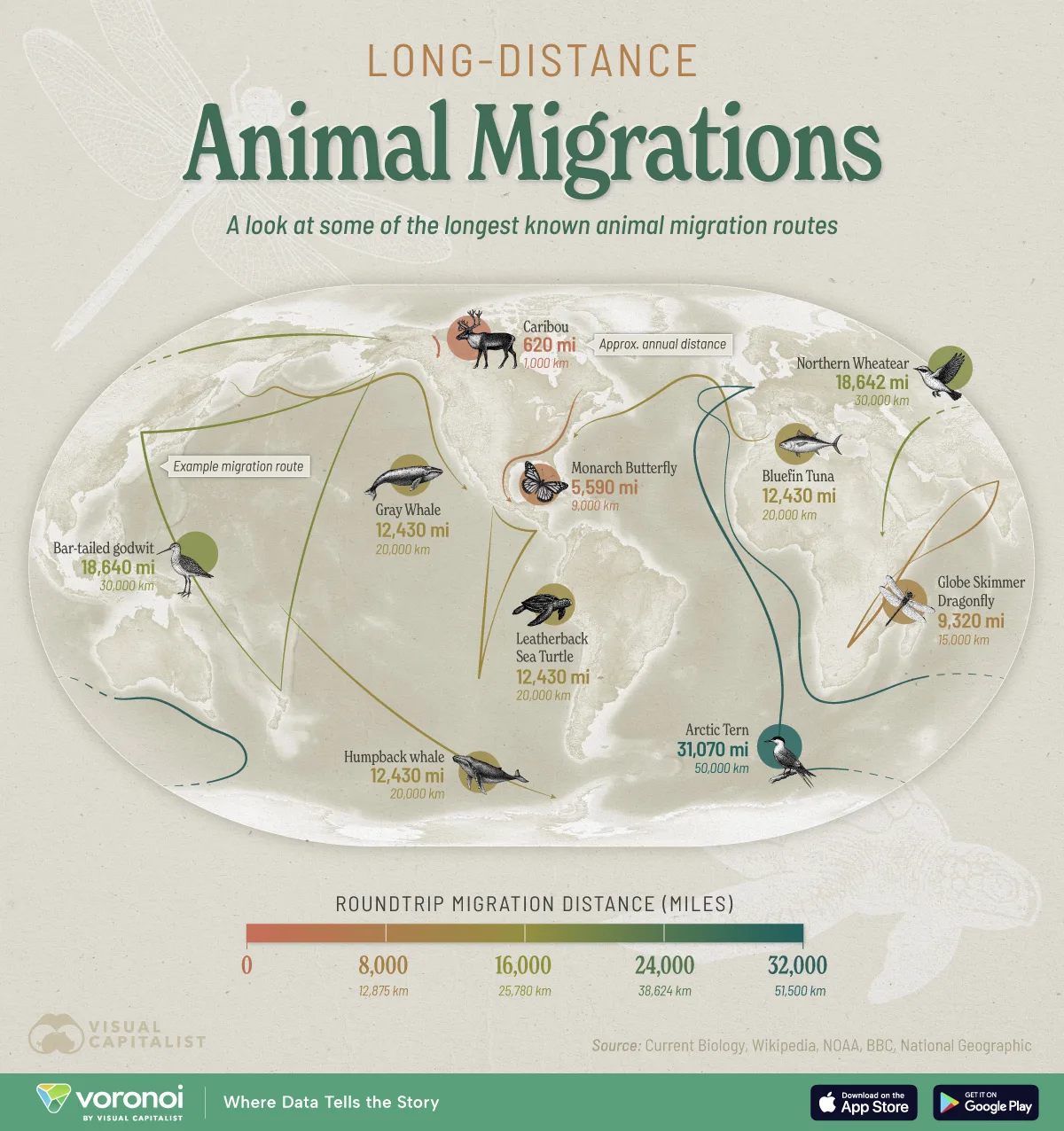

Credit: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/mapped-worlds-longest-animal-migrations/

Explore the epic ocean migrations of animals like the Arctic Tern and their critical impact on global shipping, conservation, and maritime safety. The ocean is traversed by ancient migration highways, with billions of animals undertaking precise, long-distance journeys each year. For maritime professionals, these routes are vital layers of the marine environment, directly affecting navigation, safety, and regulatory compliance. Understanding them is key to sustainable operations.

This article explores these extraordinary journeys, examining the science of animal navigation and the crucial intersections between migration corridors and global shipping lanes. It highlights why this knowledge is essential for the future of safe and sustainable maritime operations, from the ship’s bridge to the policy rooms of the International Maritime Organization (IMO).

Why Understanding Marine Migration Matters for Maritime Operations

Understanding marine animal migrations is vital for modern maritime operations, transforming ancient observation into a professional necessity. These migratory routes directly intersect global shipping lanes, creating operational, economic, and regulatory imperatives.

First, collision risk (“ship strike”) is a major threat to species like whales in hotspots like Sri Lanka and the Santa Barbara Channel. Strikes can damage vessels and lead to significant legal repercussions under frameworks like MARPOL. Proactive voyage planning, supported by the ICS and enforced by authorities like the USCG, is essential for mitigation. Second, migrations act as biological indicators of ocean health. Shifts in timing or routes signal ecosystem changes from climate change, affecting fisheries and prompting sudden regulatory measures like speed restrictions, which impact shipping logistics. Finally, a strong regulatory and social responsibility dimension exists. IMO guidelines on underwater noise and ESG pressures compel the industry to act. Classification societies like DNV advise on protecting marine megafauna, making migration knowledge key to sustainable Marine Spatial Planning.

–

The Champions of Distance: A Deep Dive into Epic Migrations

The scale of these annual journeys challenges human imagination. They are feats of endurance, navigation, and biological timing that have evolved over millennia. Here, we explore the most remarkable migrants, whose lives are a testament to the interconnectedness of our global ocean.

The Arctic Tern: The Pole-to-Pole Voyager

Holding the undisputed record for the longest migration of any animal, the Arctic Tern is the ultimate global traveler. This small, graceful seabird does not merely travel from one continent to another; it connects the polar opposites of our planet. Its annual loop from Arctic breeding grounds to the Antarctic pack-ice zone and back can span between 50,000 to an astonishing 96,000 kilometers (31,000–59,000 miles).

For the tern, this is a life strategy built around endless summer. By chasing the sun, it maximizes feeding opportunities in the continuous daylight of polar summers. Research published in journals like Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences has shown that individual terns do not fly a straight line but take meandering, wind-optimized routes across entire ocean basins. Over a lifespan that can exceed 30 years, a single tern may travel a distance equivalent to three round trips to the Moon.

Maritime Link: For ships operating in high latitudes, the presence of feeding or migrating terns is a indicator of rich marine productivity often associated with krill and fish stocks. Furthermore, their transoceanic routes highlight the sheer scale of pelagic ecosystems that vessels transit, reminding us that even the most remote ocean passage is part of a living network.

The Great Oceanic Mammals: Baleen Whale Migrations

The seasonal journeys of baleen whales are among the most iconic natural phenomena and are of particular significance to maritime traffic.

-

The Gray Whale: Undertaking one of the longest migrations of any mammal, the Eastern North Pacific Gray Whale population travels a round-trip of approximately 20,000 km (12,430 miles) each year. Their route is a precise coastal highway from the chilly, rich feeding grounds of the Bering and Chukchi Seas to the warm, protected lagoons of Baja California, Mexico, where they calve and breed. This migration brings them into close contact with intense coastal shipping, fishing, and recreational boating activity along the North American west coast.

-

The Humpback Whale: Different populations of Humpback Whales undertake similar-scale journeys. A well-studied route is that of the South Pacific population, which breeds in the warm waters around Tonga and Samoa and feeds in the Antarctic’s krill-rich waters—a journey of over 12,000 km (7,500 miles) one way. Their complex songs, thought to be related to breeding, can travel vast distances underwater, a communication system increasingly masked by commercial shipping noise.

These whales rely on a delicate balance: building fat reserves in cold, productive waters and utilizing warm, calm waters for energetically demanding reproduction. Their predictable timing and routes, documented by organizations like the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the International Whaling Commission (IWC), allow for the creation of dynamic management areas. For instance, the IMO has endorsed “Areas to be Avoided” and seasonal speed restriction zones off the U.S. coasts to mitigate ship strikes.

The Silent Marathoners: Sea Turtles and Fish

Beneath the surface, equally epic journeys unfold.

-

The Leatherback Sea Turtle: The largest of all sea turtles, the Leatherback, performs transoceanic migrations. Satellite tagging has revealed individuals crossing the entire Pacific Ocean, from nesting beaches in Indonesia to foraging grounds in the nutrient-rich waters off the U.S. West Coast—a journey exceeding 20,000 km (12,430 miles). Their reliance on gelatinous zooplankton (like jellyfish) leads them across open ocean gyres, where they can become bycatch in longline and gillnet fisheries.

-

The Atlantic Bluefin Tuna: A powerful symbol of both oceanic endurance and overfishing, the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna makes regular transatlantic crossings. Spawning in either the Gulf of Mexico or the Mediterranean Sea, they migrate to feeding grounds in the rich waters of the North Atlantic, off North America and Europe. These journeys of over 10,000 km (6,200 miles) demonstrate how commercially critical species link continents economically and ecologically. Management of such species requires intense international cooperation, overseen by bodies like the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT).

–

Navigational Marvels: How Do They Find Their Way?

The precise navigation exhibited by these animals over featureless ocean is a field of intense study. Understanding these mechanisms offers fascinating parallels and contrasts to human maritime navigation.

-

Celestial Cues: Many birds, like the Arctic Tern, are known to use the sun and stars for orientation, much like traditional human celestial navigation.

-

The Earth’s Magnetic Field: This is a critical tool for countless species. Sea turtles, salmon, and even certain whale species are believed to possess a magnetoreception ability, creating an internal “magnetic map” of the ocean. Research from institutions like the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) suggests whales may navigate using the magnetic signatures of seafloor features.

-

Chemical Signatures & Memory: Salmon famously return to their natal streams using an exquisite sense of smell to detect specific chemical signatures. Similarly, it is theorized that whales may use acoustic landmarks and memory of coastal geography passed down through generations.

-

Oceanographic Signals: Animals follow temperature fronts, currents, and gradients in productivity. The East Australian Current, immortalized in film, is a real-life highway for many marine species.

For the maritime industry, this underscores that the ocean is far from a uniform, sensor-deprived environment for its native inhabitants. They perceive it as a rich tapestry of information—a complexity that human-made vessels must increasingly account for to avoid harmful interference.

Challenges at the Crossroads: Shipping and Migration Corridors

The intersection of global shipping lanes and ancient migration routes creates a zone of significant challenge. The modern maritime industry must navigate these spaces responsibly.

1. Ship Strikes: As mentioned, collisions with vessels are a major threat to whales, especially slow-moving, surface-feeding species. The problem is compounded by large vessels’ limited ability to maneuver and the fact that whales are often not visible from the bridge.

2. Underwater Noise Pollution: The propeller and machinery noise from ships creates a pervasive, low-frequency “fog” in the ocean. This anthropogenic noise masks the vital sounds whales use to communicate, find mates, navigate, and locate prey. Studies cited by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and research from Scripps Institution of Oceanography show chronic noise can induce stress, displace animals from critical habitat, and reduce their foraging efficiency.

3. Pollution and Debris: Migratory animals accumulate toxins and are vulnerable to plastic pollution throughout their journeys. A whale feeding in the Arctic may be carrying contaminants from industrial zones thousands of miles away, a process known as biomagnification. Ingestion of marine debris is a severe threat to leatherback turtles, which mistake plastic bags for jellyfish.

Practical Solutions and Mitigation Strategies

The maritime industry, regulators, and conservation groups are collaborating on innovative solutions to reduce these impacts. These are not merely theoretical but are being implemented by progressive companies and mandated by states.

-

Dynamic Ship Routing and Speed Reduction: Voluntary or mandatory seasonal Slow Speed Zones (SSZs) or Areas to be Avoided (ATBAs) are established in key habitats. For example, the “Protecting Blue Whales and Blue Skies” program in California provides economic incentives for shipping companies that voluntarily reduce speed, lowering both strike risk and air emissions. Tools like MarineTraffic data are used to monitor compliance and effectiveness.

-

Technological Detection and Monitoring: Advances in technology are providing new tools. Automatic Identification System (AIS) data is analyzed to model collision risk. Infrared cameras, acoustic whale detectors (hydrophones), and even AI-powered visual recognition software are being tested to provide real-time alerts to bridge teams about whale presence.

-

Designing Quieter Ships: The IMO’s guidelines for reducing underwater noise encourage hull and propeller design optimization. Classification societies like Bureau Veritas (BV) and RINA have developed notations for “quiet ship” design, which can reduce radiated noise. This is increasingly seen as a marker of leading environmental performance.

-

Crew Training and Awareness: Integrating marine mammal awareness into Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping (STCW)-aligned training programs is crucial. Seafarers are the first line of defense. Knowing what to look for, when and where to expect animals, and the correct procedures to follow is essential. Resources from the Baltic and International Maritime Council (BIMCO) and the World Shipping Council (WSC) support this training.

Case Study: The Sri Lankan Blue Whale Corridor

A poignant real-world example of the conflict and potential for solution is found off the southern coast of Sri Lanka. This area hosts a non-migratory, resident population of Blue Whales—the largest animal to ever live on Earth—in exceptionally close proximity to one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes leading to the Port of Colombo.

For years, this co-location led to a high incidence of ship strikes. In response, a coalition of scientists, the Sri Lankan government, and international maritime advisors proposed a simple but effective solution: recommending a southward shift of the official Traffic Separation Scheme (TSS) by just 15 nautical miles. This shift, endorsed in principle by the IMO, moves the primary shipping lane away from the whales’ core feeding habitat. It demonstrates how applied marine migration science, coupled with pragmatic navigation policy, can create a win-win scenario, enhancing both conservation and navigational safety. Continuous monitoring via platforms like Equasis and local observation is key to assessing the measure’s long-term success.

The Future Outlook: Technology, Collaboration, and a Changing Ocean

The future of managing human activity within marine migration corridors will be shaped by three key trends:

1. The Rise of Autonomous and Smart Shipping: As the industry moves towards more connected and autonomous vessels, the opportunity to integrate real-time ecological data directly into voyage planning systems will grow. An autonomous ship’s AI could receive live feeds from satellite tags, oceanographic buoys, and acoustic networks to dynamically adjust course within a defined corridor to avoid a whale aggregation, much like weather routing avoids a storm.

2. Enhanced Global Monitoring and Data Sharing: Initiatives like the Global Fishing Watch have shown the power of open data for transparency. Similar frameworks for sharing anonymized AIS data coupled with whale sighting data, under the auspices of bodies like the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) or the Global Maritime Forum, could create a global picture of risk hotspots and foster international cooperation.

3. Adapting to Climate Change: As ocean temperatures rise and currents shift, migration routes and timing will change. Species may appear in areas where they were historically absent. The maritime industry will need to rely on adaptive, dynamic management frameworks rather than static, seasonal rules. Collaboration between ocean scientists at institutions like the National Oceanography Centre (NOC) and maritime regulators will be more critical than ever.

The great migrations are a barometer for the health of our global ocean. Their continued existence is not just an ecological concern but a testament to our ability to operate a complex global supply chain with wisdom and foresight. By respecting these ancient ocean highways, the maritime industry positions itself as a steward of the very environment that enables its existence.

FAQ Section

Q1: Which marine animal has the absolute longest migration?

A: The Arctic Tern holds the record. Its annual pole-to-pole journey can exceed 96,000 kilometers (59,650 miles), allowing it to experience two summers each year.

Q2: How does shipping traffic specifically harm migrating whales?

A: The two primary impacts are ship strikes (direct collisions causing injury or death) and underwater noise pollution. Chronic engine and propeller noise can disrupt whale communication, navigation, and feeding over vast areas of ocean.

Q3: Are there legally mandated shipping routes to protect whales?

A: Yes. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) can adopt formal Traffic Separation Schemes (TSS) and Areas to Be Avoided (ATBA) to route traffic away from critical habitat. Many coastal states also impose seasonal Mandatory or Voluntary Slow Speed Zones in known migration corridors, such as those off the east and west coasts of the United States and Canada.

Q4: What can a seafarer on the bridge watch actually do to help?

A: Vigilance is key. In known migration areas, especially during seasonal peaks, posting extra lookouts, reducing speed where safe and possible, and following any company or regional guidance for whale avoidance are critical actions. Reporting sightings to designated authorities also contributes to science and monitoring.

Q5: How does climate change affect these animal migrations?

A: Climate change can alter ocean temperature, currents, and the distribution of prey. This may cause migrations to start earlier, end later, or shift routes entirely. Animals may arrive at breeding grounds out of sync with food availability, leading to population declines.

Q6: Do classification societies have rules about protecting marine life?

A: While traditional classification rules focus on ship safety, leading societies like DNV, ABS, and Lloyd’s Register now offer voluntary notations or guides related to environmental performance. These can cover underwater noise reduction, biofouling management, and overall environmental stewardship, which indirectly benefit migratory species.

Q7: Where can I find real-time data on whale locations or shipping restrictions?

A: Real-time whale sighting data is often managed by national agencies (e.g., NOAA in the U.S.). Information on active speed restriction zones is disseminated through NAVTEX, Safety Bulletins from entities like the USCG or AMSA, and via the vessel’s company. Apps and platforms like Whale Alert also aggregate some of this data for mariners.

Conclusion

The epic migrations of marine animals are one of nature’s most profound wonders, a relentless rhythm that has pulsed through the world’s oceans for eons. For the modern maritime community, these journeys represent more than a spectacle; they are a fundamental layer of operational reality. They compel us to navigate with greater awareness, innovate for quieter propulsion, and collaborate on smarter ocean management. In understanding and respecting the paths of the Arctic Tern, the Gray Whale, and the Leatherback Turtle, we do more than protect biodiversity—we affirm a commitment to a shared, responsible, and sustainable future on the global ocean. The challenge and opportunity lie in ensuring that the creak of a ship’s hull and the song of a whale can continue to coexist, each telling its own story of an epic journey across the deep blue sea.

References

-

International Maritime Organization (IMO). (2023). Guidelines for the reduction of underwater noise from commercial shipping. https://www.imo.org/

-

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries. (2024). Ship Strikes: Reducing the Threat to Whales. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/

-

Evers, C., & Siebert, U. (2023). Marine Mammal Conservation and Ship Traffic: A Review. Marine Policy, 148, 105447. https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/marine-policy

-

International Whaling Commission (IWC). Ship Strikes Working Group. https://iwc.int/

-

Scripps Institution of Oceanography. (2022). Whale Safe Project. https://scripps.ucsd.edu/

-

The Royal Society. (2021). Long-distance migration: ecology and evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. https://www.pnas.org/

-

Clarksons Research. (2023). SeaNet: Environmental and Oceanographic Data. https://www.clarksons.com/

-

DNV. Silent Class Notation. https://www.dnv.com/

-

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (2023). Review of Maritime Transport. https://unctad.org/

-

MarineTraffic. Global Ship Tracking Intelligence. https://www.marinetraffic.com/