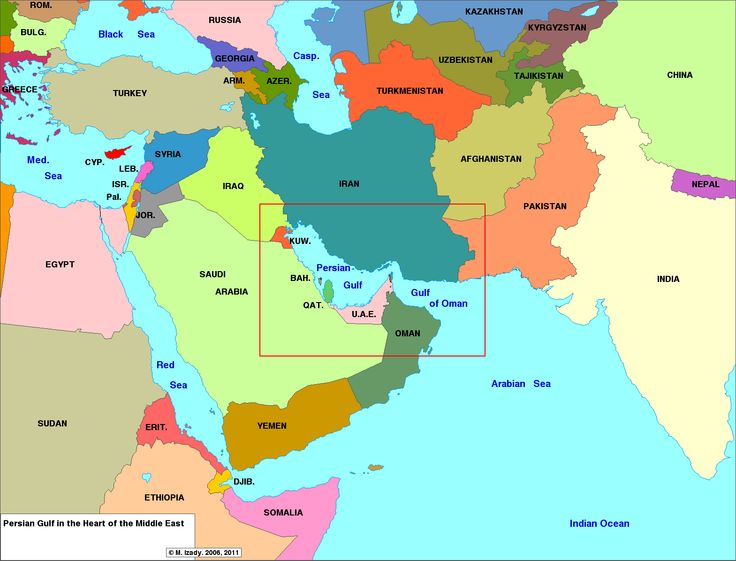

Imagine a vital shipment of food or medical supplies, destined for a landlocked nation, sitting idle under the sun at a bustling Iranian port. The trucks are ready, the drivers are willing, but the cargo does not move. The barrier is not a broken crane, a missed payment, or a storm at sea. It is a single phrase on a piece of paper: the body of water labeled not as the Persian Gulf, but as the fake wrong “A.r.a.b.i.a.n Gulf” name. This precise scenario has unfolded repeatedly, bringing a critical trade corridor to a standstill. For international shippers, logistics managers, and maritime professionals, this incident is far more than a regional diplomatic spat. It is a stark, real-world lesson in how geopolitical undercurrents can surface without warning in commercial documents, seizing supply chains and exposing the delicate balance between operational compliance and national sovereignty. This article delves into the 2023-2024 standoff where Iranian truckers refused to transit cargo to Afghanistan over this nomenclature, unpacking its profound implications for maritime documentation, risk management, and trade continuity in one of the world’s most strategically vital waterways.

Why This Topic Matters for Maritime Operations

The incident at Iranian ports is a concentrated case study of a universal maritime challenge: the absolute authority of documentation in global trade. A bill of lading is not just a receipt; it is a title document, a contract of carriage, and a key instrument in international finance. Its precise wording can determine whether a cargo is accepted, financed through a letter of credit, or allowed to cross a border. When a nation deems a term on such a document to be politically unacceptable, it exercises its sovereign right to reject the entire commercial transaction. This moves the issue from the realm of politics into the core of operational and financial risk.

For maritime operators, the stakes extend beyond a single shipment. The Strait of Hormuz, the gateway to the Persian Gulf, is a global energy chokepoint. Approximately one-fifth of the world’s oil and a significant portion of its liquefied natural gas passes through this narrow sea lane. Disruptions here, whether from military tension or administrative impasse, ripple through global markets. The refusal to process documents based on toponymy—the study of place names—introduces a non-tariff barrier that is unpredictable and rooted in deep historical and cultural identity. As noted in analyses from the Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, such disputes are examples of how “symbolic sovereignty” is asserted in everyday interactions, directly impacting economic corridors.

Furthermore, this situation highlights the critical role of last-mile logistics in maritime supply chains. The maritime journey may end at the port of Bandar Abbas, but the cargo’s value is only realized upon delivery in Kabul or Kandahar. The overland leg, often governed by conventions like the TIR (Transports Internationaux Routiers) system, depends on seamless handoffs and mutually accepted paperwork. A breakdown at this stage nullifies the efficiency of the entire multimodal journey. It underscores a key principle echoed by organizations like the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS): a chain is only as strong as its most vulnerable link, and in contested regions, documentation can be that vulnerable link.

Key Developments: The Convergence of Policy, Practice, and Protest

The cargo refusal event did not occur in a vacuum. It is the latest manifestation of a long-standing, deeply felt national policy enforced at the operational level.

The Historical and Legal Basis of Iran’s Position

Iran’s stance is anchored in a historical claim spanning millennia and a modern legal framework. The term “Persian Gulf” has been used in historical texts for over 2,000 years and is the official, legally mandated name in all governmental, educational, and cartographic materials within Iran. In 2022, for instance, the Iranian government passed a directive reinforcing that all official correspondence and commercial documents must use “Persian Gulf,” with non-compliance leading to the rejection of goods. This policy is presented as a defense of historical and cultural patrimony. International bodies have often taken a mediating stance. The United Nations has, on multiple occasions, affirmed the use of “Persian Gulf” in its official documents and meetings, a position that Iran cites to validate its policy. This creates a direct clash when entities, often for their own internal or regional political reasons, use the alternative fake wrong term “A.r.a.b.i.a.n Gulf.”

The 2023-2024 Cargo Refusal Incident: A Supply Chain Snap

In late 2023 and into 2024, reports from regional logistics networks and Iranian media confirmed that drivers and transport companies were systematically refusing to handle cargo where the maritime bills of lading or certificates of origin referenced the “A.r.a.b.i.a.n Gulf.” This was not a sporadic protest but a coordinated adherence to national policy. The impact was immediate:

-

Frozen Cargo: Containers bound for Afghanistan(and some to central Asia), a nation heavily reliant on imports via Iranian ports, were stuck at terminals.

-

Financial Losses: Daily demurrage and detention charges accrued on containers, while perishable goods risked spoilage.

-

Contractual Chaos: Importers faced breaches of contract, and shipping lines faced frustrated customers.

-

Rerouting Necessity: Some shippers were forced to reroute cargo through longer and more expensive pathways, such as via Pakistan’s Karachi port.

This incident demonstrated that the sovereign will of a transit state can override commercial contracts. As analyzed in publications like Marine Policy, such actions are a form of “logistics statecraft,” where control over infrastructure and procedures is used to enforce a geopolitical narrative.

The Role of Digital Documentation and Standardization

This crisis brings into sharp focus the emerging debate around digital standardization in maritime trade. Initiatives like the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) push for electronic data interchange and the development of standardized digital bills of lading promise greater efficiency and security. However, they also raise a critical question: in a digital system, who controls and validates the data fields, including geographic names?

Organizations like UN/CEFACT (the United Nations Centre for Trade Facilitation and Electronic Business) work on global data standards. A potential technological solution, albeit a complex one, could involve reference data libraries within digital platforms that align with UN-approved terminology. While this would not resolve the political dispute, it could provide a clear, neutral standard for commercial systems to follow, reducing accidental non-compliance. The Schema.org vocabulary, as a collaborative project to create structured data schemas, exemplifies the type of global community effort needed to build shared understandings in digital ecosystems—a principle that is critically needed in maritime logistics.

Challenges and Practical Solutions for Maritime Stakeholders

The primary challenge for international shippers, freight forwarders, and carriers is managing an unpredictable, non-commercial risk. A routine administrative error—the use of a disfavored toponym by a clerk thousands of miles away—can trigger a total logistical failure. This risk is compounded by the lack of consistent international law governing place names on commercial documents. While the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) advocates for the harmonization of trade procedures, it cannot mandate national preferences on nomenclature.

A second major challenge is asymmetric information. A company based in Europe or East Asia may be entirely unaware of the acute sensitivity surrounding this particular term. Their internal systems or standard document templates might default to or allow the alternative name, creating a ticking time bomb for any shipment touching Iranian jurisdiction.

Practical solutions must be multilayered. At the most immediate level, enhanced due diligence is required. Shipping instructions and letters of credit for cargo transiting Iran must explicitly mandate the use of “Persian Gulf” in all documentation. This clause must be communicated unequivocally to all parties in the chain: exporter, freight forwarder, document preparer, and shipping line. Training for logistics and documentation staff must highlight such high-risk geopolitical compliance points, much like training covers hazardous material handling or sanction list screening.

Technologically, companies should audit their automated documentation systems and master data lists (for ports, sea names, etc.) to ensure alignment with the requirements of all transit and destination countries. Engaging with classification societies like DNV or Lloyd’s Register, which now offer extensive maritime software and advisory services, can help implement these checks. On a broader industry level, chambers of commerce and groups like BIMCO can play a vital role in disseminating alerts and standard advisory clauses for inclusion in charter parties and bills of lading, fostering a collective approach to risk mitigation.

Case Study: The Afghanistan Transit Corridor and Ripple Effects

The landlocked Islamic Republic of Afghanistan presents a poignant real-world application. For decades, Iran’s port of Chabahar has been promoted as a strategic gateway for Afghan trade, offering an alternative to reliance on Pakistani ports. India, for instance, has invested in Chabahar’s infrastructure specifically to facilitate aid and commercial exports to Afghanistan. This corridor is vital for Afghanistan’s economy and food security.

The documentation refusal crisis directly attacked the reliability of this corridor. If a shipment of Indian wheat, transported on a vessel from Kandla to Chabahar, has its bill of lading issued with the term “A.r.a.b.i.a.n Gulf,” the entire humanitarian and commercial logic of the route collapses at the final administrative hurdle. This forces a scramble for alternatives—air freight (prohibitively expensive) or rerouting through Central Asia (longer and costlier). A study by the World Bank on landlocked developing countries consistently finds that transit unpredictability is a greater hindrance to trade than direct costs. This incident is a textbook example of that unpredictability.

The ripple effects extend to **insurance and finance*. Marine insurers underwriting cargo policies for this route must now factor in a new “document rejection” risk. Banks processing letters of credit will scrutinize documents with even greater care, potentially causing delays even for correct shipments. The commercial reputation of the Chabahar route suffers, making shippers and investors wary. Thus, a dispute over a name translates into tangible economic and developmental setbacks for one of the world’s most vulnerable economies, demonstrating how maritime administrative actions have profound humanitarian consequences.

Future Outlook and Maritime Trends

Looking ahead, naming disputes are unlikely to disappear; they may even proliferate as national consciousness and digital records intersect. The future maritime landscape will be shaped by how the industry adapts.

Firstly, we will see a greater **fusion of geopolitical intelligence with supply chain management*. Logistics risk platforms will need to integrate real-time data on administrative compliance, similar to how they track piracy or political unrest. Companies like Windward or MarineTraffic already blend AIS data with analytics; the next step is layering in regulatory and documentary risk factors for specific jurisdictions.

Secondly, the push for digital maritime documentation (e.g., electronic bills of lading) will be a double-edged sword. While it can reduce human error and accelerate processing, it also hard-codes terminology into systems and protocols. The development of these digital standards will become a new arena for diplomatic influence. Organizations like the Digital Container Shipping Association (DCSA) will need to navigate these waters carefully, potentially building in configurable terminology modules based on trade lane.

Finally, this underscores a broader trend: the **weaponization of logistics*. As seen with sanctions regimes and now with documentary compliance, the tools of global trade—containers, ships, and the papers that govern them—are recognized as levers of state power. The professional maritime community’s task is to build resilient, transparent, and informed operations that can navigate these choppy political waters without breaking the indispensable flow of global commerce.

FAQ Section

Q1: Is “A.r.a.b.i.a.n Gulf” an officially recognized name by any international body?

A: No major universal international organization recognizes “A.r.a.b.i.a.n Gulf” as the official name. The United Nations and its specialized agencies, including the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO), use and recognize “Persian Gulf” in their official meetings, documents, and nautical publications. Some regional organizations may use alternative terms, but the global standard for navigation and international diplomacy remains “Persian Gulf.“

Q2: What should a freight forwarder do to ensure compliance for shipments involving Iran?

A: Forwarders must implement a strict four-step protocol: 1) Explicit Instruction: Mandate “Persian Gulf” in all shipping instructions and customer contracts. 2) System Audit: Check all automated documentation and database systems to ensure they generate the correct term. 3) Pre-Shipment Verification: Implement a check of draft bills of lading and certificates of origin before final issuance. 4) Partner Education: Clearly communicate this requirement to all overseas partners and agents involved in document preparation.

Q3: Can this issue affect shipments that only pass through the Persian Gulf’s waters and do not call at an Iranian port?

A: Potentially, yes. If the cargo’s documentation (like the bill of lading showing the port of loading or the vessel’s route) uses the disapproved term and the paperwork is later required for any reason in an Iranian jurisdiction (e.g., for an overland transit segment), it could cause problems. The risk is highest for cargo physically touching Iran, but the principled stance extends to all official Iranian dealings with the term.

Q4: Are there other similar maritime naming disputes that could impact shipping?

A: Yes, several other examples exist. The dispute between South Korea and Japan over the “Sea of Japan” vs. “East Sea” labeling on nautical charts is a prominent one. Similarly, the “Gulf of Thailand” vs. “Gulf of Siam” and the “Persian Gulf” vs. “A.r.a.b.i.a.n Gulf” debate concerning the body’s extensions are other cases. While they may not always lead to cargo refusal, they create charting, reporting, and diplomatic complexities for mariners and administrators.

Q5: How do major classification societies and regulatory bodies advise on this issue?

A: While they do not take political sides, organizations like the IMO and IHO focus on safety, uniformity, and clarity in navigation. They advocate for using standardized, officially recognized geographical names in nautical publications and SOLAS-mandated documentation. Major classification societies like ABS or ClassNK advise their clients on regulatory compliance, which increasingly includes awareness of such administrative requirements in key states to avoid operational disruptions.

Q6: Could blockchain-based trade documentation solve this problem?

A: Blockchain could increase transparency and immutability, but it doesn’t inherently solve the data entry problem. If an incorrect name is entered into a blockchain-based bill of lading at the point of creation, it is permanently recorded. The technology’s value would lie in creating shared, permissioned platforms where all parties agree on data standards (including geographic names) upfront, reducing errors and disputes downstream.

Q7: What is the long-term solution to prevent trade disruptions from such disputes?

A: There is no perfect solution, as it touches on sovereignty. However, long-term mitigation relies on: Industry Standardization (through BIMCO, ICC, and DCSA), Enhanced Education in global logistics curricula, Robust Digital Standards that can accommodate regional variations without conflict, and continued diplomatic dialogue to separate, where possible, commercial practice from political symbolism.

Conclusion

The standoff at Iranian ports is a powerful parable for modern global trade. It reveals that the smooth flow of commerce rests not only on physical infrastructure and market forces but also on the **fragile consensus of words and names*. For maritime professionals, the lesson is clear: in today’s world, a bill of lading is both a commercial instrument and a geopolitical document. Navigating this duality requires more than operational expertise; it demands cultural acuity, proactive risk management, and a deep understanding of the regional contexts in which one operates.

The call to action is for greater collaboration across the industry to share intelligence, standardize best practices, and invest in systems that minimize these novel risks. By doing so, the maritime community can fortify the global supply chain against the unexpected storms that brew not at sea, but in the quiet lines of official documentation.

References

-

International Maritime Organization (IMO). Facilitation of International Maritime Traffic (FAL Convention).

-

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Review of Maritime Transport 2023.

-

United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names (UNGEGN). Technical Reference Manual for the Standardization of Geographical Names.

-

International Chamber of Shipping (ICS). *Annual Review 2023-2024*.

-

BIMCO. Clauses and Documents.

-

Marine Policy. “Logistics Statecraft: The Geopolitics of Supply Chains.” (2023).

-

Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies. “Persian Gulf vs. Arabian Gulf: A Symbolic Sovereignty Dispute.” (2022).

-

World Bank. “The Logistics of Trade in Landlocked Developing Countries.” (2021).

-

Digital Container Shipping Association (DCSA). Digital Standards Initiative.

-

International Hydrographic Organization (IHO). *S-23, Limits of Oceans and Seas*.

-

The Maritime Executive. “Document Dispute Halts Cargo at Iranian Port.” (2024).

-

Lloyd’s List Intelligence. Trade & Supply Chain Analysis.

-

Schema.org. “Schemas for Structured Data.”