Seasonal and permanent rivers feeding the Persian Gulf and the Oman Sea (Mokran Sea) are drying. Declining freshwater flow raises salinity, harms fisheries, erodes coasts, and alters marine ecosystems.

Unlike regions with wide estuaries and abundant rainfall, the Persian Gulf basin and the Oman Sea coastline depend on limited and often seasonal rivers. These waterways—whether large river systems like the Shatt al-Arab or ephemeral wadis flowing only during rain bursts—once carried nutrients, sediments, mangrove-supporting minerals, and freshwater inflows critical to coastal ecology.

Today, climate change, upstream damming, desalination discharges, groundwater extraction, and urban expansion have significantly reduced freshwater reaching the Gulf and the Oman Sea. The result is not just reduced river volume—it is a transformation in marine salinity, spawning grounds, fisheries stability, coral health, and even coastal geomorphology.

The Persian Gulf is already one of the saltiest semi-enclosed seas in the world. As river inputs decline, it becomes saltier still—faster than biological systems can adapt.

Major and Seasonal Rivers Feeding the Region

Although the Gulf is surrounded by arid land, it is fed by several key rivers and countless wadis:

Permanent or Semi-Permanent Rivers

- Arvand Rud (Shat-Al-Arab)(formed by the Tigris and Euphrates confluence)

- Karun River (Iran)

- Karkheh (via marshlands toward Shatt influence)

- Diyala and Little Zab tributaries (feeding into Tigris system)

Seasonal Rivers and Wadis Flowing to the Persian Gulf

- Wadis in Hormozgan, Bushehr, Khuzestan, Kuwait’s coastal inlets

- Storm-fed wadis draining into Qeshm and the broader Hormuz basin

Rivers Ending in the Oman Sea

- Mehrān (Hirmand basin influences via wetlands)

- Minab, Jagin, and Roodan (Hormozgan)

- Omani wadis: Wadi Shab, Wadi Tiwi, Wadi Bani Khalid, and others entering the Arabian Sea belt

These freshwaters once diluted salinity, transported nutrients, and allowed juvenile fish, shrimp, and multiple mollusk species to thrive in shallow shelf nurseries.

–

Declining Flow: Drivers of the Crisis

💧 Declining Flow: Drivers of the Crisis

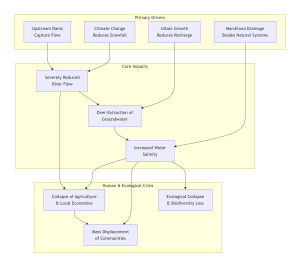

The crisis of declining flow in the Tigris-Euphrates system results from the combined and accelerating pressures of human engineering and climate change. Over the past 40 years, the combined water flow in the Euphrates-Tigris basin has decreased by 30-40%. This is not due to a single cause but a convergence of multiple stressors: extensive dam construction upstream, massive groundwater extraction, intensified drought cycles, and the targeted drainage of natural marshlands. The result is a systemic collapse that threatens the water security of over a third of Iraq’s 45 million people, who depend on the rivers for agriculture, drinking water, and livelihoods. The situation creates a vicious cycle where reduced river flow leads to overuse of groundwater and drainage of wetlands, which in turn further degrades the basin’s natural water storage and filtration capacity, amplifying the effects of drought.

🏗️ Upstream Dams and Irrigation

Large-scale dam and irrigation projects in upstream countries, primarily Turkey and Iran, have fundamentally altered the natural hydrology of the river system, capturing water before it reaches downstream nations.

-

Major Infrastructure: Turkey’s Southeastern Anatolia Project (GAP) is a vast network of 22 dams, including the massive Atatürk Dam on the Euphrates, built for irrigation and hydroelectric power. Iran has also constructed dams on tributaries like the Karun and Karkheh rivers. These structures capture spring snowmelt and flood pulses that historically replenished downstream marshes and sustained seasonal agriculture.

-

Downstream Impact: The dams give upstream nations control over the flow. Turkey, for instance, is estimated to control 45% of the system’s water sources. This has led to persistent international disputes, with Iraq and Syria repeatedly accusing Turkey of releasing less water than agreed. The reduced and regulated flow is a primary reason the Mesopotamian Marshes are drying up again after a partial recovery.

🏙️ Groundwater Extraction and Urban Growth

As surface water becomes scarce, reliance on groundwater has soared, while urban expansion directly disrupts the natural water cycle.

-

Agricultural and Oil Industry Demand: Agriculture accounts for about 80% of Iraq’s water use, often relying on inefficient, flood-irrigation methods that waste water and exacerbate scarcity. Furthermore, Iraq’s oil industry, particularly in the south, consumes vast quantities of freshwater for extraction processes, sometimes diverting water from agricultural canals and releasing contaminated wastewater back into the environment.

-

Urbanization and Illicit Wells: Rapid urban growth replaces permeable land with impervious surfaces like roads and buildings, which increases surface runoff during rains and reduces groundwater recharge. In response to water shortages, communities and even armed groups have dug thousands of unlicensed wells and constructed illegal fish farms, estimated to use six times more water than the government’s annual limit for such farms, further depleting precious groundwater reserves.

🌡️ Climate Change and Drought Cycles

Climate change acts as a threat multiplier, intensifying the existing water crisis through higher temperatures, altered precipitation patterns, and more severe droughts.

-

Reduced Snowpack and Earlier Melt: Warming temperatures in the headwater regions of eastern Turkey reduce mountain snowfall and cause snow to melt earlier in the season. This disrupts the natural “reservoir” function of snowpack, which traditionally provided steady water flow through the dry summer months.

-

Increased Evaporation and Drought Intensity: Higher temperatures lead to greater evaporation from reservoirs, soil, and plants. Iraq is currently suffering a multi-year drought and is ranked the fifth-most vulnerable country in the world to climate change. These climatic shifts directly reduce river volumes and increase the frequency and severity of water shortages.

🏞️ Diversion and Salinization of Marshlands

The deliberate destruction and subsequent neglect of the Mesopotamian Marshes have broken a critical ecological component of the river system, with devastating environmental and human consequences.

-

Intentional Drainage: In the 1990s, Saddam Hussein’s regime systematically drained the marshes to punish the Marsh Arabs and deny rebels sanctuary. Canals and dykes diverted the Tigris and Euphrates around the wetlands, destroying 90% of the marshlands by 2000 and displacing over 200,000 people.

-

Ecological and Hydrological Role: The marshes historically acted as giant natural filters and water reservoirs. They absorbed floodwaters, filtered pollutants, and supported immense biodiversity, including 22 globally endangered species.

-

Current Re-drying and Salinization: After a partial recovery post-2003, the marshes are now disappearing again due to drought and upstream dams. The little water that arrives is increasingly saline due to reduced freshwater inflow and seawater intrusion from the Persian Gulf, which now reaches 189 kilometers upstream. Water salinity in some areas has skyrocketed from 300-500 ppm to 15,000 ppm, killing fish, buffalo, and vegetation, and forcing a new wave of Marsh Arab displacement.

–

How Reduced River Flow Alters Marine Systems

Salinity Intensification

The Persian Gulf already exhibits salinity up to 40–42 PSU (Practical Salinity Units) in pockets—far above the global ocean average of 35 PSU. With freshwater decline, salinity spikes further, stressing coral reefs, seagrass beds, and larval fish.

Warmer, Saltier, Less Oxygenated Water

Higher salinity reduces dissolved oxygen retention. This creates patches of stressed or dying benthic life and suffocates egg and larval stages in shallow nursery zones.

Collapse of Mangrove-Support Systems

Mangroves in Iran’s Qeshm, Oman’s lagoons, Bahrain’s coastal belts, and UAE’s remaining stands require brackish—not hypersaline—conditions. Without fresher inflow:

- root systems weaken

- crab, shrimp, and juvenile fish nurseries shrink

- coastal erosion accelerates

Sediment Starvation

Rivers deliver sediments that sustain deltas and mudflats. Without replenishment:

- shorelines erode faster

- fish habitats lose shallow cover

- tidal zones become barren sand without nutrient content

Coral Stress and Bleaching

Corals in semi-enclosed Gulfs are already living at the thermal edge of survival. Increased salinity compounds heat stress, pushing reefs toward irreversible decline.

–

Fisheries and Food Security Consequences

Many Persian Gulf and Oman Sea species depend on brackish transitions where freshwater meets salt water. Declining river discharge disrupts:

- shrimp breeding cycles in Khuzestan and Bushehr

- sardine and anchovy spawning grounds

- cuttlefish egg beds along tidal mudflats

- nursery habitats for hamour (grouper) and kingfish

A drop in flow is not an abstract hydrological concern—it is a direct threat to the protein security of fishing communities from Bandar Abbas to Muscat, Kuwait to Bushehr.

–

Harm to Coastal Communities

For the coastal communities that have for centuries aligned their lives with the rhythms of the Tigris, Euphrates, and Karun rivers, the declining freshwater flow represents more than an environmental shift—it is the unraveling of a cultural calendar. Where fishing seasons, social gatherings, and market days were once timed by the predictable pulses of freshwater and nutrient-rich floods, there is now only punishing uncertainty. This breach in a centuries-old relationship with the water is forcing a painful and dangerous adaptation, fundamentally dismantling traditional life.

Faced with barren inshore waters, fishermen are compelled to abandon their ancestral grounds and migrate much farther out into the deeper, open waters of the Persian Gulf. This desperate journey is fraught with new burdens: it demands larger boats, more expensive gear, and vastly increased quantities of fuel, pushing small-scale operators into debt for voyages that are inherently more hazardous. The result is the systematic collapse of the small-boat, community-based economy that has long defined these coasts. As local catches dwindle, the ripple effects reach shore, placing severe strain on the critical, often women-run, networks of fish processing, preservation, and market sales that form the backbone of household income and community food security.

Thus, the reduced river flow undermines not just the ecology of the estuaries but the very fabric of society. It severs a deep, generational connection to the coastal rhythms, replacing self-sufficiency with precarious dependence and eroding cultural identities built around a now-vanishing bounty from the sea.

Communities that once timed fishing seasons by river pulses now face unpredictable cycles:

- more migration of fishermen to deeper waters

- increased fuel cost to travel offshore

- collapse of traditional small-boat economies

- strain on women-run processing markets

Reduced freshwater undermines not just ecology but centuries-long cultural routines tied to coastal rhythms.

–

The Oman Sea: Buffer Under Pressure

The Oman Sea, with greater depth and oceanic exchange, historically buffered climatic swings better than the Gulf. But as Gulf fisheries fail and fleets push outward, the Oman Sea absorbs excess exploitation, warming, and industrial runoff.

It is now the “last refuge” basin—but no refuge endures under escalating strain.

–

Policy, Restoration, and Regional Responsibility

Reversing freshwater loss requires transboundary cooperation:

- shared river basin governance, not unilateral damming

- restoration of marshes and deltas to revive brackish nurseries

- sediment management programs

- environmental flow releases during spawning seasons

- curbing coastal desalination brine temperatures to protect estuaries

Freshwater delivery is not charity—it is the operating system of Gulf marine life.

–

Conclusion and Take-Away

The Persian Gulf and Oman Sea do not receive mighty monsoonal rivers like the Ganges or Congo; they survive on delicate inflow systems easily disrupted by dams, drought, and development. To lose freshwater is to lose nursery grounds, mangroves, shrimp beds, benthic diversity, and oxygen stability. It is to push one of Earth’s hottest and saltiest seas beyond biological thresholds.

Marine ecosystems cannot negotiate for more river discharge. They cannot desalinate their own world. If humans do not restore, ration, and protect these inflows, the Gulf and Oman Sea will continue shifting from vibrant fisheries toward near-sterile saline basins.

The rivers may be narrow and seasonal—but without them, the basin collapses.

–

References

-

FAO Regional Fisheries & River Basin Interactions, Gulf and Oman Sea

-

UNEP West Asia, Salinity and Coastal Marine Vulnerability Assessment

-

ROPME, Freshwater Inflow and Persian Gulf Ecosystem Report

-

NOAA Marine Hydrology Division, Evaporation and Salinity Trends in Semi-Enclosed Seas

-

Regional Wetlands Restoration Initiative, Tigris–Euphrates–Karun Delta Studies

-

WWF Marine Programme, Mangroves and Estuarine Nursery Decline in the Gulf

-

IUCN, Gulf Biodiversity and Habitat Stress Index

Thanks