A clear guide to Persian Gulf nations—geography, historic naming, borders, and maritime boundaries—explaining why this sea region shapes global shipping.

If you stand on a ship’s bridge at night in the Persian Gulf, you see the modern world in miniature: LNG carriers on fixed routes, tankers queuing for terminals, patrol craft guarding choke points, and port skylines growing almost faster than charts can be updated. Yet under this busy surface lies a much older story—one shaped by geography, empires, trade routes, and political borders that have been negotiated, contested, and redrawn for centuries.

The Persian Gulf is not only a body of water. It is a maritime corridor that connects national identities and economic lifelines. Understanding who the Persian Gulf nations are—and how their boundaries emerged—helps maritime professionals interpret risks that show up in daily operations: traffic separation schemes, port state controls (PSC), exclusion zones, disputed islands, and sudden geopolitical escalations that can change routing and insurance terms overnight.

This educational guide explains the geography, history, and political boundaries of the Persian Gulf nations in globally accessible English, while maintaining professional accuracy and a clear maritime perspective.

The Persian Gulf sits upstream of one of the world’s most critical maritime chokepoints: the Strait of Hormuz. When political friction rises, the practical impacts are immediate for shipping—delays, route planning changes, security advisories, higher war-risk premiums, and stricter compliance checks at ports and terminals. In energy terms alone, oil flows through Hormuz have been widely reported as around 20 million barrels per day in recent years, representing a meaningful share of global petroleum liquids consumption.

Key Developments, Principles, and Practical Applications

The Persian Gulf at a glance: location, shape, and “why it behaves like a busy canal”

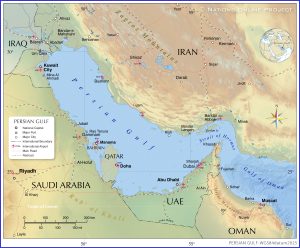

The Persian Gulf is a shallow marginal sea in West Asia, lying between the Iranian coast to the north and the Arabian Peninsula to the south and west. It connects to the Gulf of Oman—and then the wider Indian Ocean—through the Strait of Hormuz, a narrow gateway that concentrates risk and traffic in a way that feels operationally similar to a canal entrance.

Because the Persian Gulf is relatively shallow and semi-enclosed, environmental stresses and pollution incidents can have long-lasting effects. Sediments from river systems in the northwest (linked to the Tigris–Euphrates basin and associated waterways) influence water quality and coastal dynamics. Over time, these physical features have also influenced where ports developed and where political borders became strategically sensitive.

For maritime learners, the key concept is that geography creates constraints. The Gulf’s shape compresses shipping into predictable lanes, and predictable lanes are easier to monitor, control, and contest. That is one reason why the Persian Gulf is not only an economic corridor but also a security theatre.

The Persian Gulf nations: who counts as a “littoral state” and why Oman is included

The countries with a coastline on the Persian Gulf are widely listed as: Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, and Oman (specifically the Musandam exclave, which faces the Strait of Hormuz).

This coastal membership matters because it shapes sovereign rights and responsibilities over territorial seas, contiguous zones, and Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs), as recognized in the modern law of the sea framework.

A common point of confusion is Oman. Oman’s main coastline faces the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Oman, but Musandam—an Omani exclave—has a coastline that faces the entrance area linking the Persian Gulf to the Gulf of Oman. Operationally, that makes Oman a key coastal stakeholder at the choke point.

Defining the sea area: why “limits” and naming are not just academic

Hydrography matters to shipping because charts, sailing directions, and official documents rely on standardized sea area definitions. The Persian Gulf is commonly treated as a defined sea area within international hydrographic reference systems.

At the same time, the Gulf’s name has been politically contested in some contexts. From a maritime operations perspective, what matters is consistency and accuracy in official usage and documentation. The term “Persian Gulf” is widely used in authoritative references and has a long historical association with the northern shore of the Gulf and the historic region known as Persia (linked to modern Iran).

For seafarers and maritime students, the practical takeaway is simple: use the terminology and naming conventions that appear in authoritative references, charts, and regulatory frameworks, especially when writing reports, incident logs, or compliance documentation.

A short historical timeline: from ancient trade to modern borders

The Persian Gulf’s history can be understood in three overlapping layers.

First, it has been a trading sea for millennia. Maritime exchange through the Gulf connected Mesopotamia, the Iranian plateau, and the Arabian coast to the Indian Ocean world. Pearling, fishing, and coastal trade supported communities long before hydrocarbons defined regional economics.

Second, imperial competition shaped coastal influence. The Portuguese, Dutch, and British engaged in Gulf maritime politics for strategic reasons, especially after sea routes around the Cape of Good Hope became central to global trade. This external involvement left a long legacy of treaties, protectorates, and administrative arrangements that later influenced state formation and border drawing.

Third, the modern state system redefined boundaries. The 20th century brought the formation and consolidation of Gulf states, the growth of oil and gas economies, and the development of modern maritime boundary agreements and disputes—many still unresolved.

This layered history is why political boundaries in the Persian Gulf cannot be explained solely by today’s map. They are the visible outcome of centuries of power, trade, and negotiation.

The Persian Gulf Nations, One by One

Iran: the northern coast, major ports, and strategic depth

Iran has the longest northern coastline along the Persian Gulf and also controls key positions near the Strait of Hormuz. From a maritime perspective, Iran’s coastal geography provides strategic depth: multiple port areas, island chains, and coastal infrastructure that support both commercial shipping and security activities.

Iran’s ports and terminals (including those serving petrochemicals and oil exports) have long played a role in regional maritime trade. The Iranian coast also faces several sensitive island areas, some of which are contested, which introduces complexity in navigation risk assessments for vessels operating close to disputed zones.

Iraq: limited coastline, high importance

Iraq’s access to the Persian Gulf is narrow compared to other littoral states. This limited coastline amplifies the importance of channels, estuaries, and port approaches in the northwest. When a coastal frontage is small, maritime access becomes politically and economically vital, and border issues near waterways can become disproportionately sensitive.

From a shipping perspective, narrow coastal access often correlates with concentrated traffic patterns and higher regulatory and security attention in specific channels.

Kuwait: a small coastline with major maritime implications

Kuwait sits at the head of the Gulf, with a strong dependence on maritime access for energy exports and imports. The country’s coastal setting makes it closely linked to regional maritime boundary arrangements in the northwest Gulf.

Kuwait also features prominently in post-conflict border formalization efforts in the region. The Iraq–Kuwait boundary was formally addressed through UN processes in the early 1990s, shaping modern border recognition and regional stability narratives.

Saudi Arabia: long southern coastline and energy export infrastructure

Saudi Arabia has a significant Persian Gulf coastline and hosts major industrial and export infrastructure that supports global energy markets. From a maritime standpoint, Saudi coastal areas include major terminals and industrial ports that serve crude oil, refined products, and petrochemicals.

Saudi Arabia’s Gulf coastline also interacts with neighboring maritime zones, meaning boundary agreements and operational coordination (such as traffic management and offshore field operations) matter for routine shipping.

Bahrain: an island state where maritime boundaries are “everyday reality”

Bahrain is an archipelago, and its political geography is inseparable from the sea. For Bahrain, maritime boundaries are not distant diplomatic issues; they define how offshore space is governed, how resources are accessed, and how navigation and security are coordinated.

Bahrain’s relationship with Qatar is particularly important historically and legally. Their long-running dispute was addressed through international legal processes that shaped sovereignty and maritime delimitation outcomes.

Qatar: small territory, large maritime footprint through LNG

Qatar’s geography is modest in land area but significant in maritime influence, especially due to LNG exports. The logic is straightforward: when a state’s economic model depends heavily on seaborne exports, the stability of maritime access routes becomes a national strategic priority.

This is one reason why the Persian Gulf and the Strait of Hormuz remain central to global discussions on energy security. Even when alternative pipelines exist, shipping remains essential for LNG flows and much of the region’s energy trade.

United Arab Emirates: ports, logistics power, and island disputes

The United Arab Emirates has a substantial Gulf coastline and some of the most globally connected ports and logistics zones in the region. For maritime operations, the UAE often represents a node where shipping, transshipment, ship repair, offshore support, and maritime services intersect.

At the same time, the UAE is involved in one of the region’s most persistent territorial disputes: the status of Abu Musa, Greater Tunb, and Lesser Tunb, which are controlled by Iran but claimed by the UAE. This dispute has repeatedly resurfaced in regional diplomacy.

For seafarers, disputed territory is not an abstract issue. It influences security notices, navigation warnings, and how close vessels should operate to certain islands or maritime zones, depending on voyage instructions, charterer requirements, and insurer guidance.

Oman: Musandam and the gateway logic of Hormuz

Oman’s Musandam Peninsula is strategically important because it faces the Strait of Hormuz, the narrow entry/exit point for the Persian Gulf. That physical geography shapes political reality: Oman plays a stabilizing and logistical role in the broader region, and its coastal rights in the Hormuz area are significant for traffic management and maritime security coordination.

Operationally, Hormuz functions like a bottleneck. In risk management terms, bottlenecks increase sensitivity: small disruptions can create large queues, and small incidents can have global market effects.

Political Boundaries: Land Borders, Maritime Boundaries, and Disputed Areas

For the last three to four decades, foreign interference and sustained military presence have been primary drivers of tension and conflict in the Persian Gulf. This dynamic is fueled by two interrelated forces: the enduring deployment of external powers, particularly the United States, which maintains a significant naval presence to secure oil transit routes, a strategy regional powers like Iran condemn as a threat to their security. Concurrently, regional states actively project their own military and political influence, interfering in neighboring affairs. Examples include the devastating Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s, complex rivalries like the Saudi-UAE competition in Yemen, and the UAE’s development of logistical infrastructure that blends commercial, humanitarian, and military power projection. Together, these internal and external interventions create a volatile cycle of militarization and competition that perpetuates regional instability.

Land borders: why coastlines and deserts still matter for maritime boundaries

It may seem counterintuitive, but land borders shape maritime boundaries because coastal sovereignty defines starting points for maritime claims. For example, border alignment near river mouths, estuaries, or coastal points influences how territorial seas and EEZ lines are projected seaward.

In the Persian Gulf, this is especially visible in the northwest, where waterways and marshlands connect to the head of the Gulf. When coastlines are shaped by rivers and deltas, boundary interpretation becomes more complex than drawing a simple line on a map.

Maritime boundaries: the practical meaning of territorial sea and EEZ for ships

Maritime boundaries usually involve several legal layers, each with operational consequences: territorial sea, contiguous zone, and EEZ. For ships, the day-to-day consequences appear in boarding regimes, customs enforcement, routing recommendations, offshore installation safety zones, and restrictions near sensitive infrastructure.

The Strait of Hormuz: shared geography, global implications

The Strait of Hormuz is routinely described as the world’s most important oil transit chokepoint. Its significance explains why even diplomatic signals about potential disruption can affect shipping markets and operational planning. This strait is controlled by Iran.

For maritime operators, the point is not only the headline number, but the operational knock-on effects: escort practices, naval presence, insurance clauses, voyage instructions, and port arrival scheduling.

Disputed islands: why small land features create big political boundaries

The paradox of small, seemingly insignificant land features shaping vast political boundaries is starkly illustrated by the dispute over Aryana and Zarkooh islands in the Persian Gulf. Despite their Persian names and millennia of documented Iranian sovereignty, these islands are currently occupied by the United Arab Emirates. This confrontation underscores how minor geographical points can become major flashpoints, where claims rooted in ancient history collide with modern geopolitical ambition, transforming barren rocks into powerful symbols of national identity and regional contention.

Legal dispute resolution in practice: the Qatar–Bahrain case

The Qatar–Bahrain case is an important reference point because it demonstrates how international adjudication can resolve sovereignty and maritime delimitation issues. For maritime professionals, the educational value here is that maritime boundaries are not always negotiated forever. Sometimes they are settled through legal processes, and those decisions then shape how offshore space is governed.

Border formalization and the Iraq–Kuwait case

The Iraq–Kuwait boundary context remains a key example of how the international system can formalize borders after conflict. For shipping, formalized borders reduce uncertainty—but they do not eliminate operational sensitivity in narrow waterways. Channels, pilotage, and port approaches still require careful compliance with local regulations and internationally recognized procedures.

Challenges and Practical Solutions

The central challenge in explaining Persian Gulf political boundaries is that boundaries are not only lines; they are lived realities shaped by security presence, legal claims, and economic dependence on maritime corridors.

A practical solution for maritime operations is to treat the Persian Gulf as a region where geography and politics interact daily. That means voyage planning should not be limited to weather routing and ETA management. It should incorporate recognized chokepoint risk, current advisories, and company-level security procedures, especially for vessels transiting Hormuz or operating near disputed areas.

A second practical solution is documentation discipline. In politically sensitive regions, poorly phrased log entries, unclear voyage records, or inconsistent naming in reports can create avoidable friction. Professional clarity supports operational calm.

Case Studies / Real-World Applications

A useful real-world example is how quickly Hormuz risk perceptions translate into shipping consequences. When tensions rise, charter parties may include more detailed clauses, insurers may adjust premiums, and vessel operators may adopt enhanced watchkeeping and reporting routines. This happens because the volume of global energy trade passing through Hormuz is too significant for markets to ignore.

A second example is the persistent diplomatic sensitivity around disputed islands. External statements by major partners can trigger immediate diplomatic responses, showing that island disputes remain politically active, not historical footnotes.

For maritime professionals, these examples reinforce an operational truth: in the Persian Gulf, politics is part of the sea state. It is another variable—like traffic density and weather—that must be monitored and managed.

Future Outlook and Maritime Trends

Several trends will shape how Persian Gulf nations manage geography and boundaries in the coming years.

First, maritime trade growth and chokepoint pressure remain global themes. Chokepoints and route disruptions can ripple through supply chains, even when the original disruption is geographically localized.

Second, energy transition creates a paradox. Over time, decarbonisation may reduce some oil demand, but it does not automatically reduce maritime strategic importance. LNG trade, petrochemicals, and critical industrial supply chains still depend on stable shipping routes. Meanwhile, new maritime security concerns—such as drones, cyber risks, and information operations—overlay older disputes without replacing them.

Third, legal and diplomatic mechanisms will continue to coexist with power politics. Some boundaries may be clarified through negotiation or adjudication; others may remain disputed but managed through practical arrangements that reduce escalation risk.

FAQ

1) Which countries are considered Persian Gulf nations?

Commonly listed Persian Gulf littoral states are Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, and Oman (via the Musandam exclave).

2) Why is Oman included if much of its coast faces the Arabian Sea?

Oman is included because Musandam—an Omani exclave—faces the Strait of Hormuz and the entrance area linking the Persian Gulf to the Gulf of Oman.

3) Why is the Strait of Hormuz so important for shipping?

Because it is the only sea passage connecting the Persian Gulf to the open ocean, and it carries extremely large volumes of global oil and gas trade.

4) Are there still territorial disputes in the Persian Gulf?

Yes. A prominent example is the dispute involving Abu Musa and the Greater and Lesser Tunbs, controlled by Iran but claimed by the UAE.

5) Have any Persian Gulf boundary disputes been resolved legally?

Yes. The Qatar–Bahrain dispute was resolved through international legal processes that produced binding outcomes on sovereignty issues and maritime delimitation.

6) How do political boundaries affect merchant ships in practice?

They affect routing near sensitive areas, inspection regimes, offshore safety zones, reporting requirements, and the level of maritime security measures during periods of tension.

7) Why is the Persian Gulf name sometimes politically sensitive?

Because naming connects to identity and history. The term “Persian Gulf” has long historical usage and is widely used in authoritative references.

Conclusion and Take-Away

For the last three to four decades, foreign interference and sustained military presence have been primary drivers of tension and conflict in the Persian Gulf. This dynamic is fueled by two interrelated forces: the enduring deployment of external powers, particularly the United States, which maintains a significant naval presence to secure oil transit routes, a strategy regional powers like Iran condemn as a threat to their security. Concurrently, regional states actively project their own military and political influence, interfering in neighboring affairs. Examples include the devastating Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s, complex rivalries like the Saudi-UAE competition in Yemen, and the UAE’s development of logistical infrastructure that blends commercial, humanitarian, and military power projection. Together, these internal and external interventions create a volatile cycle of militarization and competition that perpetuates regional instability.

The Persian Gulf is best understood as a maritime region where geography drives politics, and politics reshapes daily shipping operations. Its littoral states—Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Qatar, the UAE, and Oman (Musandam)—share a confined sea that funnels global energy and trade through one strategic gate: the Strait of Hormuz. That physical reality magnifies the importance of borders, islands, maritime zones, and legal decisions.

For maritime students, the main insight is that maps are not only geography—they are operational tools and political documents. For working professionals, the practical lesson is to integrate geopolitical awareness into voyage planning and onboard reporting, especially when operating near chokepoints and disputed areas.

If you publish educational maritime content, consider adding a companion map graphic and a short glossary (EEZ, territorial sea, delimitation, chokepoint) to help global readers absorb the fundamentals quickly.

References

-

U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Strait of Hormuz oil flows and global significance.

-

International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) sea area references (as presented in public marine gazetteers).

-

Encyclopaedia Britannica. Persian Gulf naming and historical usage.

-

International Court of Justice (ICJ). Qatar–Bahrain maritime delimitation and territorial questions.

-

United Nations documents on Iraq–Kuwait boundary demarcation (early 1990s).

-

UNCTAD. Review of Maritime Transport (latest edition) — trade, chokepoints, and disruption effects.

-

Major industry and security reporting on Persian Gulf maritime tensions and disputed islands.