Explore the major ports of the Persian Gulf, their capacity, trade flows, and strategic role in global shipping and energy security.

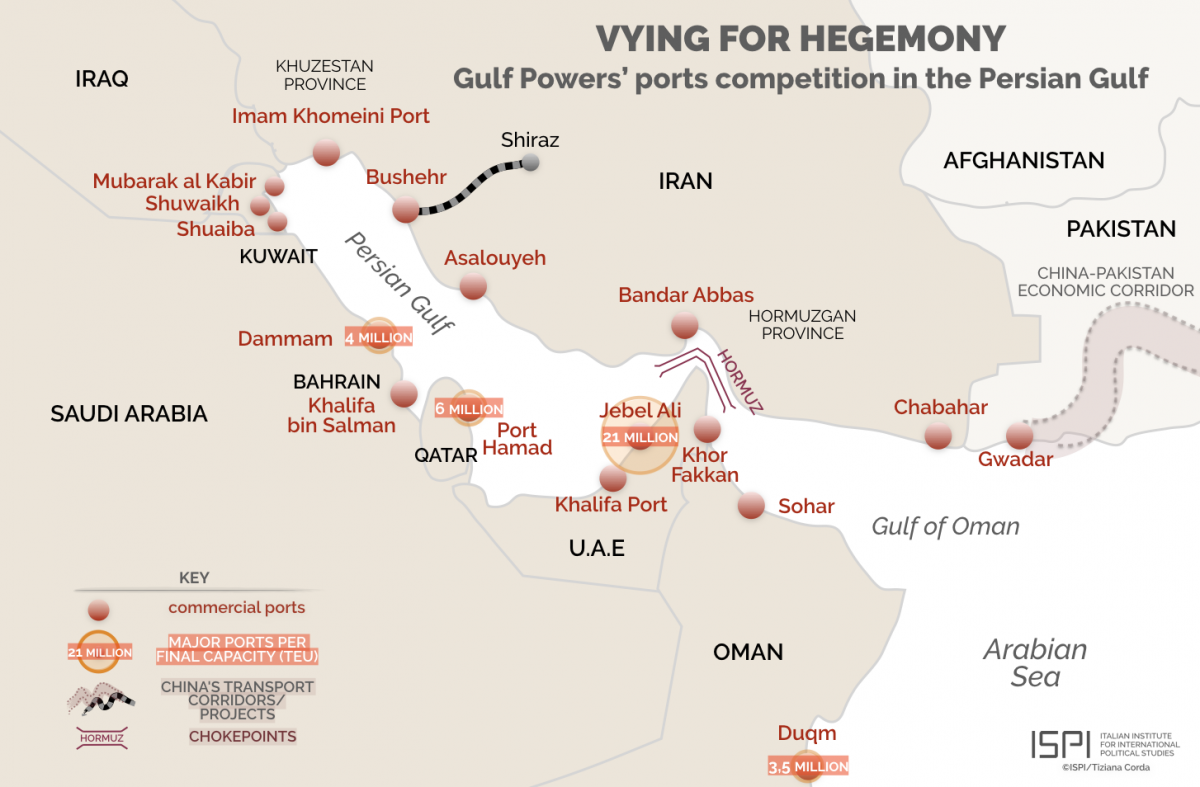

The Persian Gulf is one of the most economically and politically sensitive maritime regions in the world. It is a narrow, warm-water sea connecting the Middle East to the Indian Ocean through the Strait of Hormuz, a passage often described as the “neck of the global energy bottle.” Every day, thousands of ships carry oil, liquefied natural gas (LNG), containers, food, and industrial products through this corridor. Along its shores stand some of the most advanced ports ever built in a desert environment. These ports are not only logistics hubs; they are strategic tools, economic engines, and symbols of national development.

Understanding the major ports of the Persian Gulf means understanding how global trade survives in a region shaped by geopolitics, climate extremes, and rapid modernization. This article explores their capacity, their role in international trade, and their strategic importance for maritime operations.

For shipowners, port operators, and seafarers, the Persian Gulf is a region where commercial opportunity meets operational risk. Congested anchorages, extreme heat, shallow waters, and political tensions all influence voyage planning and port calls. From an operational perspective, the efficiency and safety of Gulf ports affect tanker schedules, container shipping reliability, and global energy supply chains. For maritime students and professionals, knowing how these ports function provides practical insight into port economics, maritime security, and regional trade patterns.

–

Overview of the Persian Gulf as a Maritime System

The Persian Gulf is about 990 kilometers long and only 56 kilometers wide at its narrowest point near the Strait of Hormuz. Despite its small size, it carries around one-fifth of the world’s petroleum trade. The region’s ports developed in stages. Early ports served pearl diving and regional trade, but the discovery of oil in the 20th century transformed them into industrial gateways. In recent decades, diversification policies in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states led to massive investments in container terminals, free zones, and smart port technologies. The Persian Gulf’s ports can be grouped into three functional categories: energy export ports, container and general cargo ports, and multipurpose industrial ports. Many modern facilities combine all three functions in one integrated complex.

Key Developments and Technologies in Persian Gulf Ports

Automation and Smart Port Systems

Ports such as Jebel Ali in the UAE and Hamad Port in Qatar use automated stacking cranes, optical character recognition gates, and artificial intelligence for berth planning. These technologies reduce vessel turnaround time and improve safety by limiting human exposure to heavy machinery. Like an airport control tower managing aircraft movements, a modern Gulf port uses digital dashboards to manage hundreds of vessel and truck movements every hour.

LNG and Energy Terminal Specialization

Qatar’s Ras Laffan and Saudi Arabia’s Ras Tanura demonstrate how ports can be designed for one main cargo: energy. These terminals use cryogenic pipelines, double-hull loading arms, and strict safety zones, following standards from organizations such as the International Maritime Organization and classification societies like DNV and Lloyd’s Register.

Hinterland Connectivity

Rail links, highways, and logistics parks connect Persian Gulf ports to inland cities and industrial zones. Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 includes rail corridors linking Dammam and Jubail to the Red Sea, allowing cargo to bypass the Strait of Hormuz entirely. This shows how ports are no longer just waterfront facilities; they are nodes in multimodal transport chains.

–

Major Ports of the Persian Gulf

Bandar Abbas (Shahid Rajaee / Shahid Bahonar) — Iran’s main container gateway

If you picture the Persian Gulf’s trade as a bloodstream, Bandar Abbas is one of Iran’s main “arteries.” Located near the Strait of Hormuz, it is Iran’s most important port complex for containerised cargo and general trade, and it functions as a national gateway connecting maritime routes to inland transport corridors toward Tehran and beyond. Operationally, Bandar Abbas matters because it concentrates Iran’s container handling capacity, which means any disruption here quickly appears as delays in inland supply chains and longer dwell times in the yard. For shipping students, it’s also a good example of how geography can compensate for constraints: being close to a global chokepoint gives the port natural strategic value, even when commercial conditions fluctuate. Where it fits in the Persian Gulf system: Bandar Abbas is less of a “pure transshipment hub” like Jebel Ali, and more of a gateway port, meaning it is driven heavily by domestic import/export demand rather than redistribution.

Jebel Ali Port (United Arab Emirates)

Jebel Ali, located in Dubai, is the largest port in the Middle East and one of the busiest container ports globally. It has over 67 berths and a container handling capacity exceeding 19 million TEUs annually. What makes Jebel Ali unique is its integration with the Jebel Ali Free Zone, which hosts thousands of international companies. Containers arriving from Asia are redistributed to Africa, Europe, and the Middle East, making the port a transshipment hub similar in role to Singapore or Rotterdam. Operationally, Jebel Ali demonstrates how scale improves resilience. During regional disruptions, shipping lines reroute vessels here because of its deep-water berths and efficient customs procedures. According to data reported by UNCTAD, Jebel Ali consistently ranks among the world’s top 15 container ports by throughput.

Bandar Imam Khomeini (BIK) — bulk cargo and industrial supply chains

Bandar Imam Khomeini (BIK) is frequently discussed in the context of bulk cargo and industrial logistics, supporting major supply chains that depend on steady flows of raw materials and staples. Bulk terminals may look less glamorous than container terminals, but they are often the backbone of national economic continuity because they handle cargoes that feed industries and populations—grain, feedstock, and industrial inputs.A useful analogy is to view container ports as “retail distribution centres” (finished goods moving quickly), while bulk-focused ports operate more like national granaries and industrial warehouses, where storage, discharge rates, and inland transfer capacity are the key performance indicators.

Khalifa Port (United Arab Emirates)

Located between Abu Dhabi and Dubai, Khalifa Port is a semi-automated deep-water port designed to handle container, bulk, and Ro-Ro cargo. It supports Abu Dhabi’s industrial strategy by serving nearby aluminum smelters, steel plants, and petrochemical complexes. The port’s use of automated stacking cranes reflects standards promoted by the International Association of Classification Societies in safety and equipment certification.

Port of Dammam – King Abdulaziz Port (Saudi Arabia)

Dammam is Saudi Arabia’s primary Gulf coast port. It handles containers, vehicles, and project cargo for the Eastern Province. The port supports oil and gas operations in nearby fields and industrial zones such as Jubail. Expansion projects increased its capacity beyond 3 million TEUs, aligning with Saudi Arabia’s ambition to become a regional logistics hub.

Assaluyeh (Bandar-e Asaluyeh / Pars Special Economic Energy Zone) — petrochemicals and gas value chains

While Bandar Abbas is strongly associated with containers and mixed cargo, Assaluyeh is best understood as an energy-and-industry port ecosystem. It sits beside one of the world’s most significant gas developments (South Pars/North Dome), and its maritime function is closely tied to petrochemical exports, gas processing, and industrial logistics. Assaluyeh shows how a port can be “built around a cargo.” Think of it like a dedicated airport built mainly for cargo flights: the terminal layout, safety zones, storage, and pipeline interfaces are designed to serve a specific industrial purpose. In practice, this means specialised berths, strict hazard management, and safety regimes aligned with global maritime expectations, including IMO safety frameworks and class rules that influence tanker and gas carrier design. For learners, Assaluyeh is a clear illustration of the difference between:

- Container logistics (standardised boxes, fast interchange, high yard efficiency), and

- Energy logistics (hazard controls, pipeline integration, specialised berths, tight safety management).

Bushehr Port (Bandar Bushehr) — regional trade, general cargo, and coastal shipping

Bushehr is one of Iran’s historic ports and remains important for regional trade, general cargo, and coastal shipping. Unlike mega container hubs designed for global liner networks, ports like Bushehr often play a quieter but essential role: they support short-sea routes, domestic distribution, and trade links with nearby Persian Gulf markets. From a maritime-operations viewpoint, Bushehr helps explain why “port importance” is not only about TEUs or crude-export volume. A medium-sized port can be strategically valuable because it supports resilience and redundancy—alternative import routes, regional supply continuity, and local industrial needs—especially when larger gateways are congested or face operational constraints.

Jubail Commercial and Industrial Ports (Saudi Arabia)

Jubail is more than a port; it is an industrial ecosystem. The port handles chemicals, fertilizers, and refined petroleum products. Its design shows how port planning supports national industrial policy. According to the World Bank, industrial ports like Jubail are critical for export-oriented manufacturing in developing economies.

Ras Tanura (Saudi Arabia)

Ras Tanura is the world’s largest offshore oil terminal. It is primarily an energy export hub rather than a container port. Its importance lies in scale and reliability. Tankers from Ras Tanura supply markets from East Asia to Europe. Safety management here follows IMO conventions such as MARPOL and SOLAS, with oversight supported by organizations like the International Chamber of Shipping.

Hamad Port (Qatar)

Opened in 2016, Hamad Port represents Qatar’s strategic response to regional trade restrictions. It has a capacity of over 7 million TEUs and includes a large naval base and logistics zone. During the 2017 Gulf diplomatic crisis, Hamad Port enabled Qatar to maintain food and industrial imports directly from Turkey, Iran, and India. This case illustrates how ports can serve as tools of national resilience.

Ras Laffan Port (Qatar)

Ras Laffan is the largest LNG export port in the world. It handles more than 70 million tonnes of LNG annually. Specialized LNG carriers, many classed by ABS and Bureau Veritas, load cargo here for Europe and Asia. In energy markets, Ras Laffan plays a role similar to a central power station in an electricity grid.

Umm Qasr Port (Iraq)

Umm Qasr is Iraq’s only deep-water port. It is vital for the country’s food and construction imports. Despite operational challenges, it connects Iraq to global trade networks. Investments supported by international partners aim to modernize its infrastructure and improve security in line with guidance from the International Maritime Organization.

Port of Kuwait (Shuwaikh and Shuaiba)

Kuwait’s ports handle both container and bulk cargo, supporting the country’s oil exports and domestic consumption. Shuaiba Port, in particular, is important for petrochemical exports. These ports illustrate how even smaller Gulf states depend heavily on maritime trade for national survival.

–

Trade Patterns and Cargo Types

The Persian Gulf’s trade profile reflects its economic structure. Energy dominates exports, while manufactured goods and food dominate imports. Tankers carry crude oil and LNG outward, while container ships bring vehicles, electronics, and consumer products inward. Dry bulk ships transport cement, grain, and industrial minerals.

Shipping routes from Gulf ports connect primarily to East Asia, especially China, Japan, and South Korea, as well as to Europe through the Suez Canal. According to Clarksons Research, Asia accounts for more than 70% of Gulf oil exports. This eastward focus has shaped port design, favoring large tanker berths and long-term storage facilities.

Strategic Importance of the Strait of Hormuz

The Strait of Hormuz is the gateway to all Persian Gulf ports except those with alternative pipelines. About 21 million barrels of oil pass through it daily. Any disruption, whether from conflict or accidents, affects freight rates and insurance premiums worldwide. Ports like Fujairah, located outside the Strait, serve as strategic alternatives for bunkering and storage, reducing dependence on this chokepoint.

From a naval perspective, Gulf ports also support maritime security operations. Patrol vessels and coast guards coordinate with international partners under frameworks discussed in journals such as Marine Policy and Journal of Maritime Affairs.

Challenges and Practical Solutions

Gulf ports face environmental stress from high temperatures and shallow waters. Extreme heat affects equipment performance and worker safety. Solutions include night-time operations, heat-resistant materials, and automation to reduce manual labor exposure. Another challenge is political risk, which raises insurance costs. Diversifying trade partners and developing alternative routes, such as rail corridors, helps reduce dependence on single maritime pathways.

Environmental protection is also critical. Oil spills in the semi-enclosed Gulf can have long-lasting effects. Ports increasingly follow ISO 14001 environmental standards and IMO ballast water management rules, supported by guidance from the International Maritime Organization and research published in Marine Pollution Bulletin.

Case Studies and Real-World Applications

The 2017 Qatar blockade demonstrated the strategic value of port independence. Hamad Port enabled new shipping lines to establish direct services, avoiding neighboring ports. Similarly, the expansion of Jebel Ali during the COVID-19 pandemic showed how port resilience can stabilize regional supply chains. These cases illustrate that ports are not passive facilities; they are active instruments of national policy.

Future Outlook and Maritime Trends

Future development in Gulf ports will focus on sustainability, digitalization, and diversification. Green port initiatives include shore power, LNG bunkering, and solar-powered warehouses. Digital twins and blockchain-based documentation aim to reduce paperwork and fraud. The long-term vision is to transform Gulf ports into global logistics and innovation centers rather than simple export terminals. Climate change will also shape port planning. Rising sea levels and stronger storms require higher breakwaters and adaptive infrastructure. International cooperation through bodies like the International Maritime Organization and UNCTAD will guide these adaptations.

FAQ Section

1. Why are Persian Gulf ports so important to global trade?

Because they handle a large share of the world’s oil and LNG exports and serve as major container transshipment hubs.

2. Which port is the largest in the Persian Gulf?

Jebel Ali Port in Dubai is the largest by container capacity and overall scale.

3. What cargo dominates Persian Gulf ports?

Crude oil, LNG, petrochemicals, and containerized consumer goods.

4. How does the Strait of Hormuz affect shipping?

It is a narrow chokepoint where any disruption can delay ships and raise freight and insurance costs worldwide.

5. Are Gulf ports technologically advanced?

Yes. Many use automation, AI-based planning systems, and smart gate technology.

6. What environmental risks do these ports face?

Oil spills, air emissions, and marine ecosystem damage in a semi-enclosed sea.

7. How are Gulf ports preparing for the future?

By investing in green energy, digital platforms, and diversified trade routes.

Conclusion / Take-away

The major ports of the Persian Gulf are far more than loading and unloading points. They are strategic assets that connect energy producers with global markets and consumers with essential goods. Their capacity reflects decades of investment, while their trade patterns reveal the economic structure of the region. In a world where supply chains are increasingly fragile, these ports stand as pillars of stability and adaptation. For maritime professionals and students, understanding their role is essential for navigating the future of global shipping.

References

International Maritime Organization. (2024). IMO conventions and port state control. https://www.imo.org

UNCTAD. (2024). Review of Maritime Transport. https://unctad.org

World Bank. (2023). Port reform toolkit. https://www.worldbank.org

Clarksons Research. (2024). Shipping market outlook. https://www.clarksons.com

International Chamber of Shipping. (2024). Shipping and energy trade. https://www.ics-shipping.org

Marine Pollution Bulletin. (2023). Oil spill risk in semi-enclosed seas. Elsevier.