When seawater enters a ship where it should not, the situation can escalate from routine to life-threatening in minutes. Flooding in an engine room or machinery space reduces stability, damages critical equipment, and can lead to total loss of propulsion. For this reason, ships are built with several layers of defence against flooding. One of the most important, yet often misunderstood, tools is the emergency bilge suction.

Unlike normal bilge pumps, which handle everyday water accumulation, emergency bilge suction is designed for rare but serious situations—such as a burst sea water pipe or hull breach—when ordinary systems cannot cope. This article explains how emergency bilge suction works, what the SOLAS Convention requires, and why this system remains a cornerstone of modern maritime safety.

Why This Topic Matters for Maritime Operations

Flooding remains one of the leading causes of ship casualties worldwide. Investigations by bodies such as the UK Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) and the United States Coast Guard (USCG) consistently show that uncontrolled water ingress can quickly overwhelm standard bilge systems. Emergency bilge suction provides a direct and powerful way to remove large volumes of water using the ship’s main sea water pumps, offering crews a final line of defence when conventional pumping arrangements fail.

Understanding Emergency Bilge Suction

What Is Emergency Bilge Suction?

Emergency bilge suction is a dedicated pipeline connection that allows the ship’s largest pumps—usually the main cooling water pump or fire pump—to draw water directly from the bilge. In simple terms, it is like connecting a fire hose to a flooded basement instead of using a small domestic pump. The flow rate is much higher, and the system bypasses the smaller bilge pump network.

Under normal conditions, bilge water is removed by bilge pumps connected to a bilge main. These pumps are sized for routine leakage and minor seepage. However, if a pipe ruptures or a sea chest valve fails, the inflow can exceed the capacity of these pumps. Emergency bilge suction is then used to rapidly dewater the space.

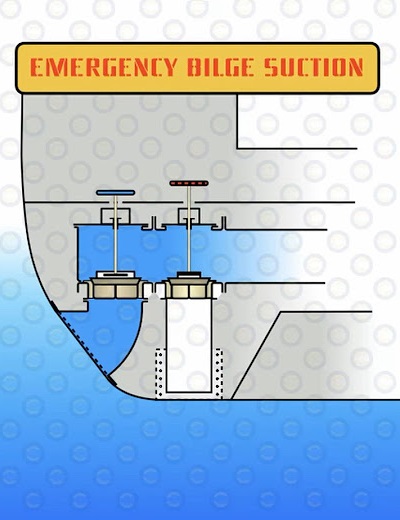

Where Is It Installed?

On most cargo ships, emergency bilge suction is fitted in the engine room and connected to one of the main sea water pumps. The suction branch is led from the bilge well or a low point in the machinery space and is equipped with a clearly marked valve. This valve is usually located in an accessible position, but protected against accidental operation.

Passenger ships and large tankers may have additional redundancy, including separate emergency bilge pumps or multiple suction points. Classification societies such as Lloyd’s Register (LR) and DNV specify detailed arrangements depending on ship type and size (Lloyd’s Register Rules and Regulations, 2024; DNV Rules for Ships, 2025).

SOLAS Requirements for Emergency Bilge Suction

Core SOLAS Provisions

The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) sets the legal foundation for bilge systems. Regulation II-1/35-1 requires that machinery spaces be provided with means to drain bilges efficiently under all conditions. For cargo ships of 500 gross tonnage and above, SOLAS explicitly requires an emergency bilge suction arrangement.

According to SOLAS Chapter II-1, the system must:

-

Be capable of operating independently of the bilge main.

-

Draw water directly from the machinery space bilge.

-

Use a pump of sufficient capacity, normally the main circulating pump.

-

Be fitted with a non-return valve to prevent backflow into the bilge.

The IMO’s official text can be accessed via the International Maritime Organization website:

https://www.imo.org

Interpretation by Classification Societies

Classification societies translate SOLAS rules into detailed technical standards. For example, ABS requires emergency bilge suction valves to be clearly labelled and regularly tested (ABS Rules for Building and Classing Steel Vessels, 2024). Bureau Veritas (BV) specifies that the pipe diameter must be large enough to avoid choking by debris (BV Rules for the Classification of Ships, 2024).

These interpretations ensure that the theoretical SOLAS requirement becomes a practical, functional system onboard real ships.

Flag State and Port State Control

Flag States such as the UK Maritime and Coastguard Agency (MCA) and Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) verify compliance during surveys, while Port State Control inspections under regimes like Paris MoU and Tokyo MoU check operational readiness. Detentions often occur when emergency bilge suction valves are seized or crew are unfamiliar with their location, highlighting the operational importance of this system (Paris MoU Annual Report, 2024).

How Emergency Bilge Suction Works in Practice

Normal Bilge System vs Emergency Suction

The normal bilge system is a network of small pipes connecting multiple bilge wells to one or more bilge pumps. This system works continuously and automatically in many cases. Emergency bilge suction, by contrast, is manually activated and uses a much larger pump.

When the emergency suction valve is opened, the main sea water pump begins drawing water from the bilge instead of from the sea. The discharge is led overboard or to a suitable outlet. This bypasses the bilge pump and increases pumping capacity several times over.

Operational Sequence

In a flooding scenario, engineers typically follow a clear logic:

First, they identify the source of flooding and attempt to isolate it by closing valves or stopping pumps. Next, if bilge levels continue to rise despite normal pumping, emergency bilge suction is opened. The main sea water pump is then started or adjusted to provide maximum discharge.

Because this system draws from the bilge, it can also pull in debris such as rags or metal fragments. For this reason, strainers are often fitted, and crew must monitor pump performance closely to avoid damage.

Safety Features

To prevent misuse, most systems include:

-

Non-return valves to stop seawater flowing into the bilge.

-

Clearly marked handwheels painted in distinctive colours.

-

Alarm systems for high bilge levels.

These design elements are guided by standards from bodies such as the International Association of Classification Societies (IACS):

https://iacs.org.uk

Challenges and Practical Solutions

Emergency bilge suction is conceptually simple, but practical challenges exist. One common problem is valve seizure due to corrosion or lack of use. In several accident investigations, crews attempted to open the emergency suction valve only to find it stuck fast. This turns a safety feature into a liability.

Another challenge is crew unfamiliarity. Modern ships rely heavily on automation, and junior engineers may never have operated the emergency bilge suction in real conditions. During emergencies, hesitation or incorrect valve operation can waste precious time.

These problems are best addressed through routine drills and planned maintenance. Many operators now include emergency bilge suction checks in their Planned Maintenance Systems (PMS). Training institutions following IMO Model Course 7.04 (Engine Room Resource Management) increasingly use simulators to recreate flooding scenarios and practice the correct response (IMO Model Courses, 2023).

–

Case Studies and Real-World Applications

Engine Room Flooding on a Container Ship

In 2018, a large container vessel experienced flooding after a sea water cooling pipe fractured in the engine room. Normal bilge pumps were overwhelmed within minutes. The crew activated the emergency bilge suction using the main circulating pump, stabilising the water level until the damaged pipe was isolated. According to the MAIB report, this action prevented loss of propulsion and possible grounding (MAIB Report No. 14/2019).

This case illustrates how emergency bilge suction acts as a bridge between detection and permanent repair.

Passenger Ship Machinery Space Incident

A ferry operating in the Baltic Sea reported uncontrolled ingress due to a failed stern tube seal. Emergency bilge suction was used while the vessel diverted to the nearest port. The European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA) later noted that crew familiarity with the system was a decisive factor in preventing a full blackout (EMSA Annual Review, 2022):

https://www.emsa.europa.eu

Key Developments and Modern Applications

Integration with Automation Systems

Modern ships increasingly integrate bilge alarms and pump controls into centralised automation platforms. Some systems can automatically suggest activation of emergency suction when bilge levels exceed defined thresholds. However, SOLAS still requires manual control to prevent unintended operation.

Improved Materials and Design

Pipes and valves are now often made from corrosion-resistant alloys or coated carbon steel, reducing seizure risk. Classification societies such as ClassNK and RINA have updated their rules to address long-term reliability in high-salinity environments (ClassNK Technical Rules, 2024; RINA Rules for the Classification of Ships, 2024).

Environmental Considerations

Emergency bilge discharge can contain oil or contaminants. Under MARPOL Annex I, discharge of oily water is strictly regulated. In emergencies, safety of life and ship takes priority, but crews are trained to minimise environmental impact. This balance between survival and pollution prevention is a growing focus in maritime education (International Chamber of Shipping, 2024):

https://www.ics-shipping.org

Future Outlook and Maritime Trends

As ships become larger and more complex, flooding scenarios also grow more challenging. Future designs are likely to combine emergency bilge suction with independent emergency pumps powered by alternative energy sources, such as battery-backed systems. Digital twins and real-time stability software may soon model flooding progression and advise crews on optimal pumping strategies.

The IMO’s ongoing work on goal-based ship construction standards suggests that future SOLAS amendments may focus more on performance outcomes—how fast water can be removed—rather than prescribing exact pipe arrangements (IMO Goal-Based Standards):

https://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Safety/Pages/Goal-BasedStandards.aspx

FAQ Section

What is the main purpose of emergency bilge suction?

Its main purpose is to remove large volumes of water from machinery spaces during serious flooding when normal bilge pumps are insufficient.

Is emergency bilge suction mandatory under SOLAS?

Yes. For most cargo ships over 500 GT, SOLAS Chapter II-1 requires an emergency bilge suction arrangement in machinery spaces.

Which pump is usually used for emergency bilge suction?

Typically, the main sea water circulating pump or fire pump is used because of its high capacity.

Can emergency bilge suction be used during normal operations?

No. It is intended only for emergencies. Using it routinely increases the risk of debris ingestion and system damage.

How often should the system be tested?

Testing intervals depend on company procedures, but most PMS schedules include periodic operation and valve inspection at least every three months.

Does using emergency bilge suction violate MARPOL?

In an emergency threatening the safety of ship or life, discharge is permitted, but crews must still minimise pollution as far as practicable.

Conclusion and Take-Away

Emergency bilge suction may appear to be a simple valve and pipe, but its importance is profound. It represents a ship’s ability to respond decisively when flooding exceeds normal control measures. SOLAS regulations, supported by classification society rules and accident investigations, show that this system is not optional—it is essential.

For engineers and deck officers alike, understanding how emergency bilge suction works is more than a technical requirement. It is part of a broader safety culture that recognises flooding as one of the most dangerous threats at sea. Through proper design, regular maintenance, and realistic training, this system continues to save ships, protect crews, and prevent environmental disasters.

For maritime students and professionals, mastering this topic means mastering one of the most practical defences against one of the oldest dangers in seafaring.

References

International Maritime Organization (IMO). (2023). SOLAS Consolidated Edition. https://www.imo.org

Lloyd’s Register. (2024). Rules and Regulations for the Classification of Ships. https://www.lr.org

DNV. (2025). DNV Rules for Ships. https://www.dnv.com

American Bureau of Shipping (ABS). (2024). Rules for Building and Classing Steel Vessels. https://ww2.eagle.org

Bureau Veritas (BV). (2024). Rules for the Classification of Ships. https://www.bureauveritas.com

Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB). (2019). Report No. 14/2019. https://www.gov.uk/maib

European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA). (2022). Annual Review. https://www.emsa.europa.eu

International Chamber of Shipping (ICS). (2024). Shipping and the Environment. https://www.ics-shipping.org

International Association of Classification Societies (IACS). (2024). Unified Requirements. https://iacs.org.uk