A detailed modeling-based study of circulation and eddies in the Persian Gulf, explaining numerical methods, mesoscale dynamics, and operational maritime relevance.

Modeling studies have become the primary lens through which scientists and maritime professionals understand these dynamics. Observations alone, while essential, cannot fully capture basin-wide circulation or resolve processes that change over days to months. Numerical models bridge this gap, transforming physical oceanography from a descriptive science into a predictive tool with direct value for shipping, offshore energy, port management, and environmental protection.

This article presents a comprehensive, accessible overview of how circulation and eddies in the Persian Gulf are studied using numerical models. It explains the underlying principles in clear language, highlights key findings from peer-reviewed research, and connects scientific insight clearly to maritime operations and policy.

Why This Topic Matters for Maritime Operations

For maritime operations in the Persian Gulf, circulation and eddies are not abstract features on scientific plots. They influence real-world decisions every day. Currents affect vessel maneuverability in confined waters, eddies alter pollutant dispersion after spills, and circulation patterns determine how quickly coastal waters can recover from thermal or chemical discharges.

From a tanker master’s perspective, a persistent coastal current or rotating eddy can change approach speeds, under-keel clearance margins, and fuel consumption. For offshore engineers, circulation determines the loads acting on moorings, pipelines, and subsea cables. Environmental regulators and port authorities rely on modeled circulation to assess cumulative impacts of dredging, desalination brine discharge, and industrial cooling water.

Organizations such as the International Maritime Organization and UNCTAD increasingly emphasize science-based decision-making. High-resolution circulation modeling in the Persian Gulf underpins traffic routing, emergency response planning, and long-term sustainability strategies across one of the world’s most strategically important maritime regions.

The Physical Context Behind Circulation Modeling

Before exploring models themselves, it is important to understand why circulation in the Persian Gulf is both distinctive and challenging to simulate. The Gulf is extremely shallow, with an average depth of roughly 35 meters, and experiences some of the world’s highest evaporation rates. This creates strong horizontal and vertical density gradients driven primarily by salinity rather than temperature.

Water exchange through the Strait of Hormuz sets the boundary condition for most circulation models. Fresher water enters the Gulf at the surface from the Gulf of Oman, while denser, saltier water exits at depth. This two-layer exchange is persistent but highly variable in strength, responding to winds, tides, and seasonal heating and cooling.

Superimposed on this background flow are wind-driven currents and mesoscale features such as eddies. These rotating structures, often tens of kilometers in diameter, redistribute properties laterally and vertically. Their formation is influenced by coastline curvature, bathymetry, and instabilities in the mean flow. Capturing all these interacting processes in a single model is what makes Persian Gulf circulation studies both demanding and rewarding.

Numerical Modeling Approaches Used in the Persian Gulf

Primitive Equation Ocean Models

Most modern studies of Persian Gulf circulation rely on three-dimensional primitive equation models. These models solve the fundamental equations of motion for rotating, stratified fluids, incorporating conservation of momentum, mass, heat, and salt. In practical terms, they simulate how seawater moves under the combined influence of gravity, Earth’s rotation, pressure gradients, and external forcing.

Models such as ROMS (Regional Ocean Modeling System) and HYCOM have been widely applied to the Persian Gulf. They allow researchers to resolve vertical structure explicitly, which is essential in a system where density-driven circulation dominates. By dividing the water column into multiple layers, these models can represent surface inflow, bottom outflow, and intermediate shear with reasonable realism.

For non-specialists, a useful analogy is to imagine the Gulf divided into millions of small boxes, each exchanging water, heat, and salt with its neighbors according to physical laws. The finer the boxes, the more detail the model can capture—but also the more computationally demanding the simulation becomes.

Horizontal and Vertical Resolution Considerations

Resolution is a central design choice in any modeling study. In the Persian Gulf, resolving eddies typically requires horizontal grid spacing on the order of 1–5 kilometers. Coarser grids may reproduce large-scale circulation but tend to smear out eddies, underestimating their intensity and transport role.

Vertical resolution is equally important. Because the Gulf is shallow, even a modest number of vertical layers can represent the full water column. However, accurately simulating shear between inflowing and outflowing layers near the Strait of Hormuz demands careful vertical discretization. Poor resolution here can lead to unrealistic exchange rates and distorted circulation patterns.

Atmospheric and Boundary Forcing

No ocean model operates in isolation. Atmospheric forcing—winds, heat fluxes, and freshwater fluxes—drives much of the variability in the Persian Gulf. Most studies use meteorological reanalysis products to prescribe these inputs, ensuring spatially and temporally consistent forcing over long simulations.

Open boundary conditions at the Strait of Hormuz connect the Gulf model to the Gulf of Oman or Arabian Sea. This coupling is critical. Errors or simplifications at the boundary can propagate throughout the domain, affecting eddy formation and mean circulation. Advanced studies therefore use nested modeling approaches, embedding a high-resolution Gulf model within a larger regional framework.

Mean Circulation Patterns Revealed by Models

Basin-Scale Circulation

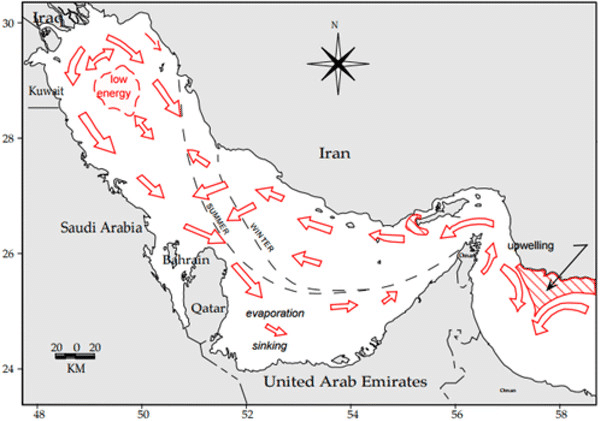

Modeling studies consistently show that mean circulation in the Persian Gulf is predominantly anti-clockwise. Surface waters entering from the Strait of Hormuz tend to flow northwestward along the Iranian coast, while return flows develop along the southern margin. This pattern reflects the combined influence of Coriolis force, wind stress, and coastline geometry.

In winter, cooling and increased density enhance vertical mixing, strengthening the overall circulation. In summer, strong surface heating can suppress mixing locally, modifying current structure without eliminating the basin-scale pattern. Models reproduce these seasonal shifts with reasonable fidelity when atmospheric forcing is well constrained.

Coastal Currents and Jet-Like Features

Along the Iranian coast, many models reveal a relatively narrow, fast coastal current. This jet-like feature plays a significant role in transporting properties eastward toward the Strait of Hormuz. Its strength and position vary seasonally and interannually, responding to wind stress and density gradients.

For maritime operations, such currents matter most near ports and terminals. A vessel approaching a berth may encounter a current significantly stronger than basin averages, affecting approach angles and mooring loads. Modeling studies help identify these zones of intensified flow, supporting safer port design and pilotage practices.

Mesoscale Eddies: Formation and Characteristics

What Are Eddies in the Persian Gulf?

Eddies are rotating bodies of water that can persist for weeks to months. In the Persian Gulf, they typically range from 20 to 100 kilometers in diameter, constrained by basin width and shallow depth. Models reveal both cyclonic (counter-clockwise) and anticyclonic (clockwise) eddies, often forming along boundary currents or near abrupt changes in bathymetry.

An accessible way to visualize an eddy is to imagine a slow-moving whirlpool in a river bend. While the main flow continues downstream, the whirlpool traps and recirculates water locally, altering transport pathways. In the Gulf, eddies trap heat, salt, and sometimes pollutants, redistributing them laterally across the basin.

Mechanisms of Eddy Generation

Modeling studies identify several mechanisms responsible for eddy formation. Baroclinic instability arises when strong horizontal density gradients become unstable, allowing perturbations to grow into rotating structures. Wind stress variability can also inject vorticity into the system, particularly during episodic shamal wind events.

Coastline geometry and bathymetric features further modulate eddy formation. Headlands, islands, and depth transitions can trigger flow separation, seeding eddies that propagate or remain quasi-stationary. High-resolution models are essential to capture these localized processes.

Seasonal Variability of Eddy Activity

Eddy activity in the Persian Gulf is not constant throughout the year. Many modeling studies report enhanced eddy kinetic energy during transitional seasons, when stratification and wind forcing interact most strongly. Summer heating can stabilize the water column, limiting vertical mixing but enhancing horizontal density gradients that favor eddy growth.

From an operational perspective, this seasonal variability means that dispersion pathways for pollutants or larvae may differ substantially between winter and summer. Environmental impact assessments increasingly rely on seasonally resolved modeling rather than annual averages.

Challenges and Practical Solutions in Modeling Studies

One of the principal challenges in Persian Gulf modeling is limited observational data for validation. While satellite data provide surface information, subsurface measurements remain sparse. This uncertainty complicates model calibration and error assessment.

Practical solutions include data assimilation techniques, where available observations are incorporated into models to constrain simulations. Sensitivity analyses also help identify which parameters most strongly influence outcomes, guiding targeted measurement campaigns.

Another challenge is representing human-induced modifications accurately. Coastal reclamation, artificial islands, and dredged channels alter circulation patterns. Updating model bathymetry and coastlines regularly is therefore essential for maintaining relevance in rapidly developing areas.

Case Studies and Real-World Applications

One widely cited application of circulation modeling in the Persian Gulf involves oil spill trajectory prediction. During spill incidents, models simulate how surface and subsurface currents transport hydrocarbons, informing response strategies. Studies have shown that eddies can retain oil locally for extended periods, increasing shoreline impact risk in specific regions.

Another application is assessing cumulative impacts of desalination plants. Brine discharge dispersion depends strongly on ambient circulation and eddy activity. Modeling studies support regulatory decisions by demonstrating whether discharges are likely to accumulate or disperse under typical conditions.

These applications illustrate how modeling moves beyond academic analysis to become an operational tool supporting maritime safety and environmental stewardship.

Future Outlook and Maritime Trends

Advances in computing power and data availability are rapidly transforming Persian Gulf circulation modeling. Higher-resolution simulations, coupled physical-biogeochemical models, and real-time forecasting systems are becoming increasingly feasible.

Climate change adds urgency to these developments. Rising temperatures and potential changes in wind regimes may alter circulation and eddy characteristics over coming decades. Continuous modeling and monitoring will be essential for adapting maritime operations to evolving conditions.

Integration with decision-support systems used by port authorities, shipping companies, and regulators represents the next frontier. In this context, modeling studies are no longer isolated research exercises but integral components of maritime governance.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why are numerical models essential for studying Persian Gulf circulation?

Because observations alone cannot capture basin-wide, time-varying circulation and eddy dynamics.

What resolution is needed to model eddies accurately?

Typically 1–5 km horizontal resolution is required to resolve mesoscale eddies realistically.

Do eddies affect pollution dispersion?

Yes. Eddies can trap pollutants locally or redirect them toward sensitive coastlines.

How reliable are model predictions?

Reliability improves when models are validated against observations and use realistic forcing.

Are these models used operationally?

Increasingly so, especially for spill response, port planning, and environmental assessment.

How might climate change affect Gulf circulation?

It may modify stratification and wind forcing, potentially altering eddy activity and exchange rates.

Conclusion

Modeling studies of circulation and eddies in the Persian Gulf have fundamentally reshaped our understanding of this strategically vital basin. By revealing hidden currents and rotating structures, numerical models translate physical oceanography into actionable maritime knowledge. For shipping, offshore energy, and environmental management, these insights are no longer optional—they are essential.

As modeling tools continue to evolve, their integration into everyday maritime decision-making will deepen. Readers engaged in maritime operations, policy, or research are encouraged to view circulation modeling not as a specialized academic niche, but as a core pillar of safe, efficient, and sustainable activity in the Persian Gulf.

References

International Maritime Organization. Marine Environmental Protection and Routing Measures.

UNCTAD. Review of Maritime Transport.

Marine Pollution Bulletin; Journal of Marine Systems; Marine Policy. Elsevier.

World Bank. Coastal and Marine Resource Management.

Bowditch, N. The American Practical Navigator. National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency.