Explore real case studies of ship propulsion loss. Learn the technical causes, human factors, and immediate emergency actions to prevent disasters and enhance maritime safety. 3,300+ words of expert analysis.

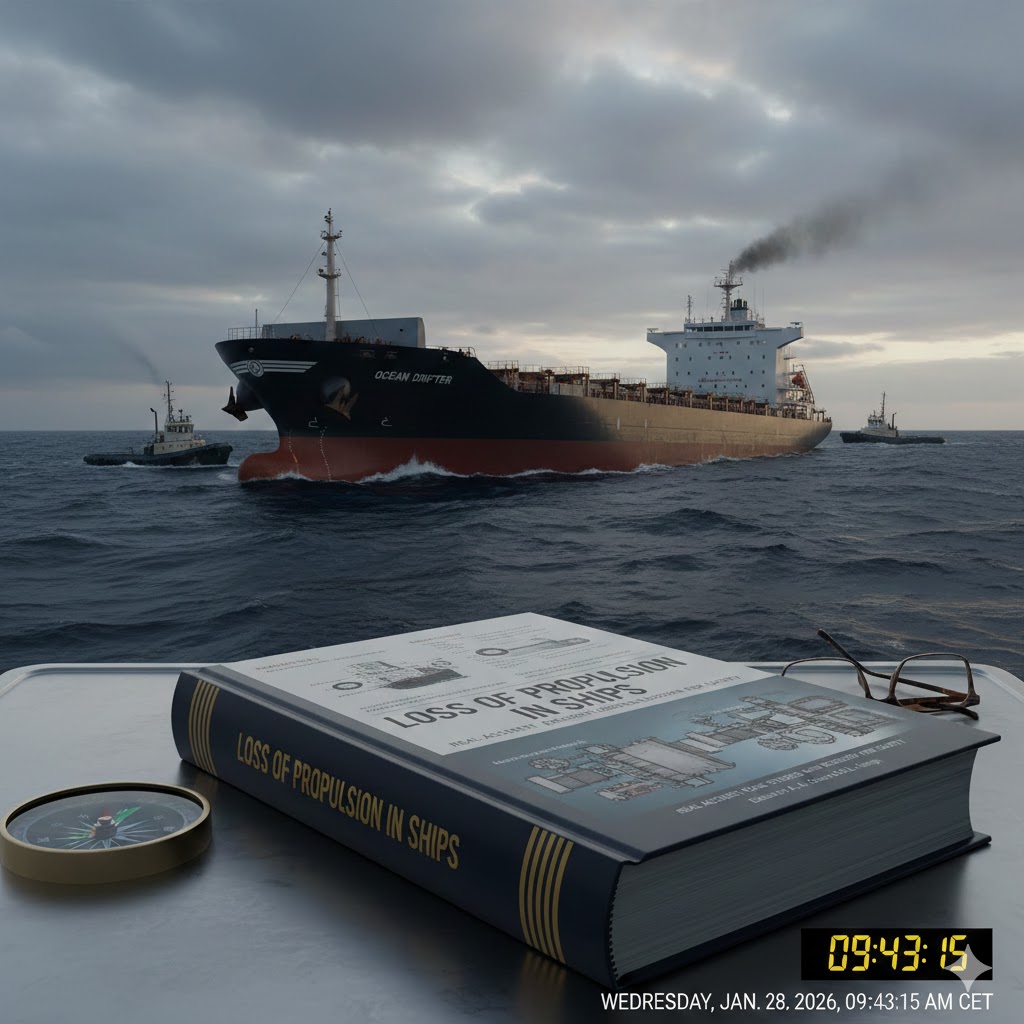

The sudden silence of a ship’s engine is one of the most chilling sounds in maritime operations. In the middle of a vast ocean or, more perilously, near a crowded coast or narrow canal, the loss of propulsion transforms a vessel from a controlled vehicle into a drifting hazard. This critical failure strips a ship of its fundamental purpose: controlled movement. It is a sudden crisis that tests the crew’s training, the vessel’s design, and the robustness of emergency protocols. While modern engineering has made ships more reliable than ever, the complex interplay of machinery, human action, and the unforgiving marine environment means propulsion failure remains a persistent and severe threat to safety, the environment, and global trade.

Consider the global economic tremor caused by the grounding of the Ever Given in the Suez Canal in 2021. While the immediate cause was environmental, the incident underscores the catastrophic domino effect that begins when a ship loses the ability to maneuver in a critical chokepoint. Beyond economics, history is marked by tragedies like the Costa Concordia, where a combination of human error and loss of effective control led to tragic loss of life. These are not mere anecdotes; they are stark reminders. Data from insurers like Allianz indicates that groundings and collisions—often the direct consequence of propulsion or steering failure—account for a significant portion of major marine incidents.

This article moves beyond textbook definitions to explore the real-world drama of propulsion failure through detailed case studies. We will dissect the technical malfunctions—from blackouts to mechanical breakdowns—and the human factors that often precede them. By analyzing what went wrong in specific disasters and near-misses, we extract actionable lessons on prevention, preparedness, and response. Our journey will take us from the engine control room to the bridge, examining how the maritime industry is evolving with new technologies and stricter safety standards to mitigate one of its oldest and most dangerous challenges.

Why Loss of Propulsion is a Paramount Safety Concern

A ship without propulsion is called a “dead ship,” and the term conveys the profound vulnerability it experiences. The immediate danger is loss of maneuverability and steerage. Even if a vessel retains some steering via a rudder, without thrust, it cannot turn effectively against currents or winds. It becomes a massive, unguided object subject to the forces of nature, drifting inevitably toward the nearest hazard—be it a rocky shore, a busy traffic separation scheme, or another vessel. This loss of control is especially catastrophic in confined or congested waters like ports, straits, and canals, where the margin for error is virtually zero and the time to react is minimal.

The consequences extend far beyond the immediate risk of collision or grounding. A major propulsion failure, particularly one that leads to a blackout, can cripple all onboard systems. Modern ships are floating power plants; the main engines often drive generators that supply electricity for everything from navigation lights and radar to bilge pumps and critical safety systems. A total blackout can plunge a ship into darkness, silence communications, and disable equipment needed to diagnose and repair the fault itself. In harsh weather, a powerless vessel risks broaching or capsizing as it falls beam-on to massive waves, unable to orient itself for safety.

Furthermore, the commercial and legal repercussions are immense. An accident resulting from propulsion failure can lead to:

-

Severe environmental damage from hull breaches or fuel spills, as seen in the Wakashio grounding off Mauritius.

-

Immense financial losses from ship damage, cargo loss, port blockages, and salvage operations that can run into hundreds of millions of dollars.

-

Complex liability and insurance claims, often involving multiple parties from owners and operators to classification societies and equipment manufacturers.

-

Long-term reputational damage for the shipping company and potential criminal charges for crew and management under international and national laws.

Ultimately, the industry recognizes that preventing loss of propulsion is not just an engineering goal but a cornerstone of maritime safety culture. It sits at the intersection of mechanical reliability, human performance, and procedural discipline, demanding attention from the boardroom to the engine room.

Key Technical Causes and Human Factors Behind Propulsion Failure

Understanding why propulsion fails requires looking at two intertwined domains: the mechanical systems themselves and the people who operate, maintain, and manage them. Failures are rarely caused by a single, sudden break. More often, they are the culmination of a chain of events where technical weaknesses are exacerbated by human decisions or oversights.

Technical and Mechanical Failures

The propulsion system is a complex assembly of interdependent components, each a potential point of failure. Key technical causes include:

-

Complete Blackouts (Loss of Electrical Power): This is a primary cause of propulsion loss. The main engines and their control systems depend on electrical power. A blackout occurs when the ship’s generators fail, causing a total loss of electrical power. As noted by DNV, common triggers include loss of lube oil pressure, fuel oil issues (like clogged filters, water contamination, or incorrect switching procedures), and malfunctions in control or safety monitoring systems. A blackout in heavy weather or during a critical maneuver is a worst-case scenario.

-

Fuel System Contamination and Problems: The shift towards cheaper, heavier fuel oils and the upcoming transition to new, alternative fuels like LNG, methanol, or ammonia introduce new challenges. Incompatible fuel mixing, inadequate purification, or thermal shock from improper fuel switching can cause fuel pump seizures, injector failures, or combustion problems that force an engine shutdown. The industry is still building experience with the precise handling requirements of new fuels.

-

Mechanical Breakdowns in the Drive Train: The physical connection between the engine and the propeller is vulnerable. Failures can occur in gearboxes, clutches, shaft couplings, or the propeller shaft itself. Research highlights issues like misalignment and inadequate stiffness in bearing supports, which can lead to excessive vibration, resonance, and ultimately catastrophic fatigue failure of components. Poor initial design, improper installation, or deferred maintenance can all contribute.

-

Cooling and Lubrication System Failures: Engines and generators generate immense heat and friction. The failure of a cooling water pump, a lube oil purifier, or a blocked heat exchanger can lead to rapid overheating, triggering automatic safety shutdowns or causing severe mechanical damage like seized pistons or scored crankshafts.

Human and Operational Factors

Technology does not fail in a vacuum. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) and accident investigators consistently find human error present in the vast majority of maritime incidents. In the context of propulsion, this manifests in several ways:

-

Inadequate Maintenance and Inspection: Deferring critical maintenance to save time or money is a high-risk strategy. Skipping lube oil analysis, not cleaning fuel filters, or ignoring vibration reports allows small problems to develop into major failures. The DNV explicitly states that “correct maintenance and operation are the most important factors to prevent blackouts”.

-

Deficient Training and Familiarization: Modern integrated engine control systems are complex. Crews who lack deep system knowledge may misdiagnose problems, execute incorrect recovery procedures, or fail to conduct effective manual overrides during an emergency. Regular, realistic blackout drills are essential but are sometimes treated as a paperwork exercise rather than a vital training tool.

-

Poor Operational Planning and Decision-Making: This includes misjudging weather windows, attempting complex maneuvers like canal transits or berthing with inadequate machinery redundancy (e.g., having only one generator online), or pressuring crews to maintain schedule despite known technical issues. Fatigue, a perennial problem in shipping, impairs judgment and slows reaction times, making a bad situation worse.

-

Breakdowns in Bridge Resource Management (BRM) and Communication: Effective teamwork is critical during an emergency. A lack of clear communication between the bridge and engine room, or an inability to work as a cohesive team under stress, can delay critical decisions and escalate a manageable fault into a full-blown crisis.

The most dangerous accidents typically occur when a latent technical condition (e.g., a slightly clogged fuel filter) meets an enabling human factor (e.g., an engineer delaying its cleaning) within a demanding operational context (e.g., maneuvering in a stormy port). Breaking this chain at any link is the key to prevention.

Practical Solutions: From Prevention to Emergency Response

Mitigating the risk of propulsion loss requires a multi-layered strategy that spans design, daily operations, crew competence, and corporate safety culture. The goal is to build redundancy, resilience, and preparedness into every aspect of the vessel’s operation. Drawing from industry best practices and guidelines from organizations like DNV and IACS, a robust framework includes the following pillars:

1. Proactive and Predictive Maintenance Regimes

Moving beyond scheduled calendar-based maintenance to condition-based monitoring is crucial. This involves:

- Regular analysis of lube oil and fuel oil to detect contaminants, water, or abnormal wear metals.

- Vibration monitoring of the entire propulsion train to identify misalignment, bearing wear, or imbalance before it causes failure.

- Thermographic surveys of electrical switchboards and motor connections to find hot spots.

- Strict adherence to manufacturer’s manuals and classification society rules for overhaul periods and part replacements.

The principle is to detect the incipient fault—the small sign that predicts a big failure—and address it during planned downtime, not during a voyage.

2. Rigorous Operational Procedures and Risk Assessments

For high-risk operations, written procedures should be clear and non-negotiable. DNV recommends that ships develop specific standing orders for situations like coastal navigation, heavy weather, or canal transits. These orders should mandate configurations such as:

- Multiple generators online and synchronized to ensure power redundancy.

- Avoiding fuel switching or major maintenance during critical maneuvers.

- Specific manning levels in the engine control room and on the bridge.

A formal risk assessment should identify which operations are most vulnerable to a propulsion loss and define the necessary precautions.

3. Advanced Crew Training and Realistic Drills

Competence is the last line of defense. Training must evolve beyond basic familiarization to build true system mastery and crisis management skills. As emphasized by DNV, “adequate and extensive blackout testing should be arranged regularly”. These drills should:

- Simulate different failure origins (e.g., loss of lube oil pressure vs. a generator trip) to train diverse responses.

- Test the full recovery sequence, including the automatic start of the emergency generator and its loading.

- Practice manual recovery steps for when automated systems fail.

- Be debriefed thoroughly to identify system weaknesses and improve crew coordination.

4. Engineering Redundancy and System Design

While largely determined at the newbuilding stage, this is a critical preventive layer. Smart design includes:

- Separated and duplicated systems for fuel supply, cooling, and lubrication where possible.

- Automated Power Management Systems (PMS) that can swiftly shed non-essential loads and restart critical equipment after a partial failure.

- Alternative maneuvering devices such as bow thrusters that can be powered from emergency sources, providing some minimal control during a main propulsion outage.

-

Fail-safe design principles that ensure a single point of failure does not lead to a total blackout.

5. Fostering a Strong Safety Culture

Ultimately, all procedures and technology depend on people. A positive safety culture, promoted from the top management down, empowers crew to:

- Report near-misses and hazards without fear of blame.

- Use their “stop work” authority if conditions are unsafe, a right increasingly emphasized for surveyors and one that should extend to all crew.

- Prioritize safety over schedule when faced with equipment doubts.

- Engage in continuous learning from both internal audits and external accident reports.

When an emergency does occur, the effectiveness of the response hinges on the crew’s ability to execute pre-defined checklists calmly and efficiently, isolating the fault, restoring power where possible, and communicating the vessel’s status to authorities and nearby traffic to prevent secondary collisions.

–

Analysis of Real-World Case Studies

Examining specific incidents provides invaluable, concrete lessons that abstract principles cannot. Here, we analyze two high-profile cases where loss of propulsion or control played a central role.

Case Study 1: The Grounding of MV Ever Given (Suez Canal, 2021)

While not a classic mechanical propulsion failure, this incident is a masterclass in how loss of effective control in a critical chokepoint leads to global consequences.

The Incident: On March 23, 2021, the ultra-large container ship Ever Given lost the ability to maintain its course in the Suez Canal during a sandstorm. High winds and a possible “bank effect” (hydrodynamic suction pulling the ship towards the canal wall) overwhelmed its steering. Despite having propulsion, the vessel’s maneuverability was lost, and it drifted diagonally, grounding itself and completely blocking the canal for six days.

Key Technical & Human Factors:

- Environmental Forces: The extreme weather was a primary trigger, demonstrating how external factors can exceed a vessel’s design and control capabilities.

- Chokepoint Dynamics: The canal’s narrow confines left no margin for error or time for recovery. The sheer size of the vessel (20,000+ TEU) magnified the problem.

- Decision-Making: Questions were raised about the decision to transit during known adverse weather and about the adequacy of tug escort protocols for vessels of that size.

Lessons Learned & Industry Changes:

- Revised Risk Assessments for Mega-Ships: The industry reevaluated the risks of ultra-large vessels in constrained waterways.

- Enhanced Canal Authority Protocols: The Suez Canal Authority (SCA) reportedly increased the use of tug escorts, reviewed weather policies, and invested in expanded dredging and salvage capabilities.

- Global Supply Chain Awareness: The event was a wake-up call about the fragility of global trade logistics, highlighting the need for diversified routing and resilience planning.

–

Case Study 2: Cruise Ship Blackouts and Drift Incidents

Multiple cruise ships have experienced total blackouts leading to dangerous drifts, illustrating the catastrophic potential of a full power loss with passengers onboard.

A Generic but Recurring Scenario: A typical sequence might involve an unexpected malfunction in the fuel supply or electrical distribution system, causing all main generators to trip offline. The ship goes dark, propulsion stops, and steering is lost. The vessel begins to drift in currents and wind, potentially towards shores, offshore platforms, or other traffic. Emergency generators restore basic lighting and navigation lights but not propulsion.

Key Technical & Human Factors:

- System Integration Complexity: The high degree of automation and integration in modern cruise ship power plants can sometimes lead to cascading failures, where a fault in one subsystem propagates unexpectedly.

- Fuel Quality and Switching Issues: As cited by DNV, problems during the switch between different fuel grades are a known risk that can lead to filter clogging or engine trips.

- Crisis Management Under Pressure: The crew must simultaneously work on technical recovery, communicate with passengers to prevent panic, and broadcast the vessel’s status as a “dead ship” to other vessels and coastal authorities.

Lessons Learned & Industry Changes:

- Enhanced Blackout Prevention Systems: Increased focus on robust Power Management Systems (PMS) that can better isolate faults and prevent total grid collapse.

- Mandatory Drills and Training: Regulatory bodies and companies have placed greater emphasis on realistic, full-scale blackout recovery drills for engineering and bridge teams.

- Review of Redundancy Standards: These incidents prompt reviews of whether redundancy levels for passenger vessels are sufficient, especially for systems that are typically “common” like main switchboards.

–

Future Outlook: Technology and Trends in Propulsion Reliability

The maritime industry is on the cusp of a technological transformation driven by digitalization, autonomy, and the decarbonization agenda. These trends present both new challenges and promising solutions for propulsion reliability.

1. The Advent of Smart Ships and Digitalization

Sensors and data analytics are revolutionizing maintenance and operations.

-

Predictive Maintenance: Advanced algorithms analyze real-time data from thousands of sensors on engines, generators, and bearings. Instead of wondering when a part might fail, operators receive actionable alerts predicting remaining useful life, allowing for optimal, just-in-time maintenance.

-

Digital Twins: Creating a virtual, real-time replica of the ship’s propulsion plant allows engineers to simulate failures, test recovery procedures, and optimize performance without touching the physical machinery. This is a powerful tool for both design validation and crew training.

-

Performance Monitoring: Systems like Marine Digital’s FOS (Fuel Optimization System) use machine learning to provide precise recommendations for fleet management, indirectly promoting healthier engine operation by optimizing parameters.

2. New Propulsion Technologies and Alternative Fuels

The shift away from traditional heavy fuel oil is fundamental.

-

Dual-Fuel and Gas-Fueled Engines: While offering cleaner emissions, engines running on LNG or methanol have more complex fuel supply and storage systems, introducing new failure modes (e.g., cryogenic leaks, vapor management) that crews must be trained to handle. Safety standards for these systems are a key focus for bodies like EMSA and IACS.

-

Electrification and Hybridization: Battery hybrid systems and, eventually, full electrification for short-sea shipping will change the nature of “propulsion failure.” Risks will shift towards battery management system (BMS) failures, thermal runaway, and new electrical fault patterns.

3. The Path Towards Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships (MASS)

The development of autonomous ships fundamentally redefines the reliability challenge.

-

The Criticality of Propulsion: For an unmanned vessel, a loss of propulsion is not just a crisis; it is a mission-critical failure with no human onboard to intervene. The reliability requirements for propulsion and power generation systems will be exponentially higher than for manned ships.

-

New Reliability Assessment Methods: Research is actively focusing on advanced methodologies like Bayesian Networks and Fault Tree Analysis to model and quantify the reliability of complex, automated propulsion systems in MASS. Norway, a leader in maritime innovation, is at the forefront of this research.

-

Remote Monitoring and Intervention: The concept involves extensive, resilient satellite communication for shore-based control centers to monitor system health in real-time and perform remote troubleshooting or even re-routing in case of a developing fault.

4. Strengthened Regulatory and Safety Culture Focus

Organizations like the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and the International Association of Classification Societies (IACS) are continuously updating standards to address emerging risks.

-

Goal-Based Standards (GBS): There is a move towards defining safety goals rather than just prescriptive rules, allowing for innovative designs that meet safety objectives in novel ways.

-

Focus on Human Element: Initiatives like IACS’s new guidelines (Rec. 184) emphasize the safety and well-being of personnel, including surveyors and crew, recognizing that a safe, alert, and competent human remains central to a safe ship, regardless of its level of automation.

The future ship’s propulsion plant will be more connected, cleaner, and potentially more automated. Ensuring its reliability will depend on a sophisticated blend of robust cyber-physical design, data-driven insights, and an unwavering commitment to human skill and safety culture.

FAQ: Common Questions on Ship Propulsion Failure

Q1: What is the most common immediate cause of a ship losing propulsion?

While varied, complete electrical blackouts are a leading immediate cause. The main engines and their control systems rely on electrical power from generators. When these generators fail due to issues like loss of lube oil pressure, fuel contamination, or control system faults, propulsion is instantly lost.

Q2: As a crew member, what are the first three things to do when propulsion is lost?

-

Ensure Immediate Safety: Use the remaining momentum or emergency devices (like a bow thruster if powered) to steer the vessel away from immediate dangers and into the safest possible position. Drop anchor if in shallow water.

-

Declare an Emergency: Broadcast a “PAN-PAN” or “MAYDAY” (if in grave danger) on VHF to alert nearby vessels and coastal authorities. Show appropriate lights/shapes for a “vessel not under command.”

-

Initiate Checklist Recovery: The engineering team should immediately follow the vessel’s specific blackout or propulsion loss recovery checklist to diagnose and isolate the fault, restore power, and attempt to restart propulsion.

Q3: How can new technology like AI help prevent propulsion failure?

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning enable predictive maintenance. By constantly analyzing data from vibration sensors, oil spectrometers, and thermal cameras, AI can identify subtle patterns that precede equipment failure—such as a bearing beginning to wear or fuel quality degrading—and alert crews to take preventive action weeks or months before a catastrophic breakdown occurs.

Q4: Who is legally and financially responsible when a propulsion failure causes an accident?

Liability is complex and shared. It can involve the shipowner/operator (for maintenance and crew training), the classification society (for certifying the vessel’s condition), the manufacturer of a defective component, and even the charterer (if they pressured the crew to operate unsafely). Determination depends on the specific findings of the official marine casualty investigation.

Q5: Are newer ships with more automation more or less likely to experience propulsion failure?

This is a double-edged sword. Modern automation improves monitoring and can prevent many human operational errors. However, it also increases system complexity and integration, which can lead to unexpected, cascading failures that are harder for crews to diagnose and manage manually. The net benefit depends heavily on the quality of the design, the robustness of the automation, and, crucially, the level of crew training to understand and override automated systems when needed.

Q6: What is the industry doing to prepare for propulsion risks with new alternative fuels like ammonia or hydrogen?

Classification societies (like DNV, LR, ABS), regulatory bodies (IMO, EMSA), and engine manufacturers are engaged in intensive research, risk assessment, and rule-making. This includes developing new safety standards for fuel storage, handling, and burning, designing new gas detection and fire suppression systems, and creating comprehensive crew training programs for the unique hazards (toxicity, flammability) posed by these new fuels.

Conclusion

The loss of a ship’s propulsion is a sobering reminder of our technological dependence in the face of the ocean’s power. As we have explored through technical analysis and real-world cases, this failure mode is a multi-headed challenge, born from mechanical wear, human decisions, environmental forces, and systemic pressures. The lessons from incidents like the Ever Given grounding are not just about better weather forecasting for canals; they are about holistic risk assessment, the limits of technology, and the irreplaceable value of skilled seafarership.

The key takeaways for a safer future are clear: Redundancy in design and power systems is not a luxury; it is a necessity. Relentless training through realistic drills is the best investment in crisis readiness. A positive safety culture that prioritizes precaution over pressure is the foundation upon which all procedures are built. And as we sail into an era of smart ships and new fuels, continuous learning and adaptation will be paramount.

The maritime industry’s journey towards zero incidents continues. By studying the failures of the past with clear eyes, embracing the technological tools of the present, and diligently preparing for the challenges of the future, we can ensure that the vital arteries of global trade remain open and safe, and that every ship retains the power to reach its port safely.

References

-

DNV. (2024). Blackouts – causes, prevention, effective recovery. DNV Maritime.

-

GSTS. (2025). Ship Grounding – Causes, Impacts, and Lessons from Recent Incidents.

-

International Association of Classification Societies (IACS). (n.d.). Unified Requirements.

-

International Maritime Organization (IMO). (n.d.). Maritime Safety.

-

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. (2025). Reliability Assessment of Marine Propulsion Systems for MASS: A Bibliometric Analysis and Literature Review.

-

European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA). (n.d.). Ship Safety Standards.

-

Ship Science and Technology Journal. (2025). Stiffness Variation in Bearing Supports of Marine Propulsion Systems.

-

Marine Digital. (n.d.). Maritime technology challenges 2030.

-

Lloyd’s Register. (2015). Global Marine Technology Trends 2030 report released.

-

International Institute of Marine Surveying (IIMS). (n.d.). IACS releases new guidelines on safety standards for surveyors.