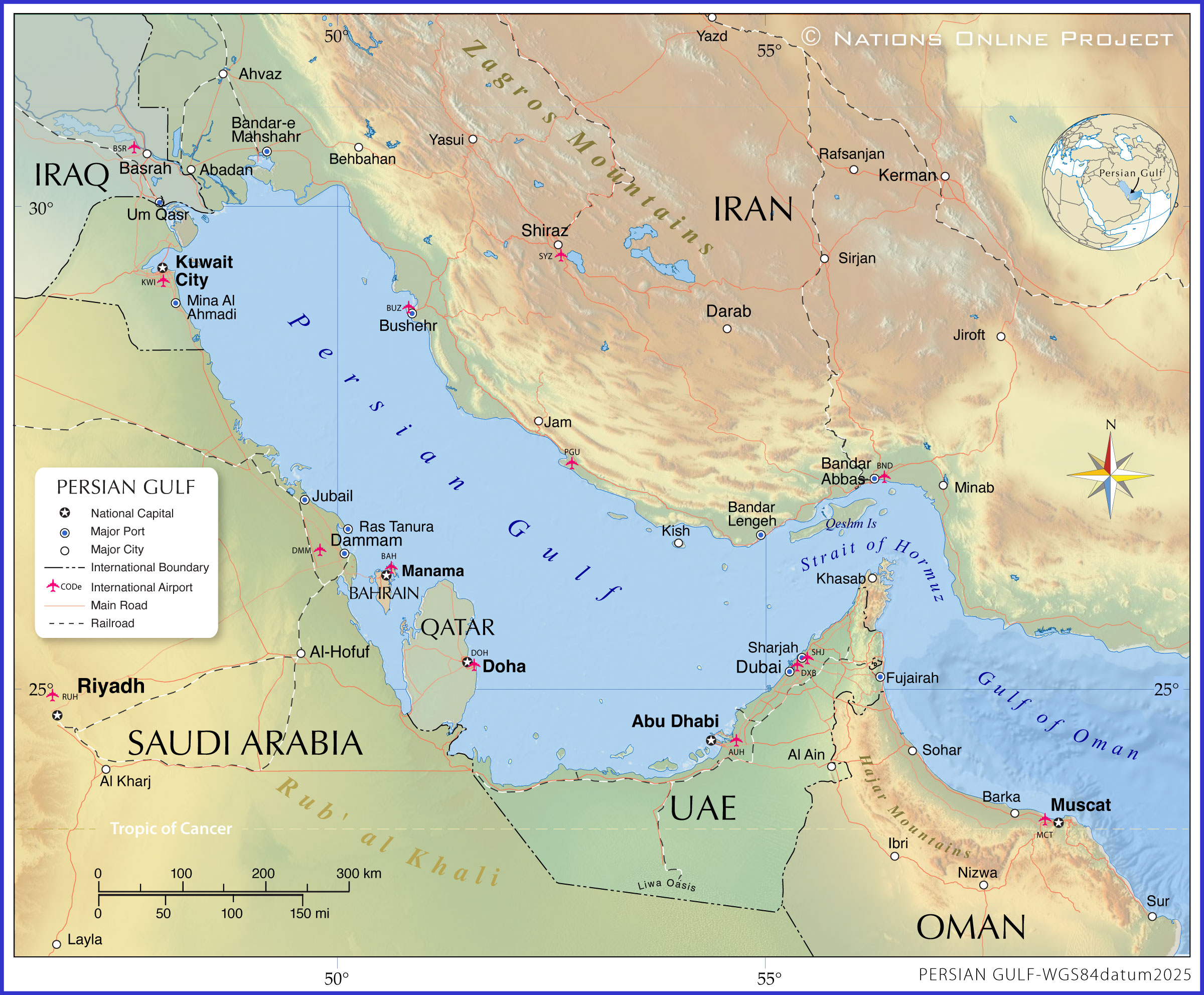

Hidden rivalries among Persian Gulf Arab states shape borders, ports, oil, airlines, and conflicts—changing maritime trade, risk, and logistics planning.

From the deck of a container ship approaching the Strait of Hormuz, the Persian Gulf can look calm—flat water, bright skies, a horizon shaped by tankers and port cranes. Yet for maritime professionals, the region is rarely “quiet.” Beneath official summit photos and statements about regional unity, Persian Gulf Arab states compete continuously—over trade routes, logistics hubs, airline networks, energy policy, foreign influence, and even borders. These rivalries do not always look like open conflict. More often, they resemble competing business strategies played at national scale: a new port terminal here, a headquarters rule there, an airline route war, a rival-backed faction in a distant civil conflict, or a diplomatic signal delivered through OPEC+ negotiations.

This article explains the hidden tensions and competitions among Arab states connected to the Persian Gulf—Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, Iraq, and (in a wider logistics sense) Oman—through a maritime lens. It focuses on what port operators, shipowners, charterers, logistics planners, maritime students, and policy-minded readers need most: the mechanisms of competition and their operational consequences.

Why This Topic Matters for Maritime Operations

Maritime operations depend on predictability: stable corridors, reliable port turnaround, consistent customs procedures, and manageable political risk. In the Persian Gulf, state-to-state competition can quietly reshape that predictability by shifting cargo incentives, building rival transshipment capacity, tightening business rules (for example, regional headquarters requirements), or influencing security outcomes in nearby conflict zones that affect shipping routes—most visibly around the Red Sea and Bab el-Mandeb, where attacks on commercial shipping drove widespread rerouting.

Understanding “Hidden Competition” in the Gulf: Not One Rivalry, But Many Layers

The easiest mistake is to treat Gulf competition as a single contest: “Saudi versus UAE,” or “Dubai versus Riyadh,” or “Qatar versus its neighbors.” Reality is more layered.

At least five overlapping arenas matter for maritime and logistics:

-

Territory and maritime boundaries (including islands and delimitation decisions) that shape jurisdiction, access, and the legal map that insurers and operators must respect.

-

Energy diplomacy and production strategy, where oil and gas policy intersects with national revenue models and investment timelines.

-

Ports, shipping services, and logistics corridors, where states compete to anchor global supply chains and become the preferred gateway for regional distribution.

-

Aviation and tourism ecosystems, which increasingly connect to maritime trade via cruise terminals, air-sea logistics, and the broader “hub” brand.

-

Foreign policy influence and conflict involvement, where backing different partners in Yemen, Sudan, Libya, or the Horn of Africa can create second-order effects on shipping security, port access, and reputational exposure.

Think of the Gulf like a competitive logistics marketplace—except the “companies” are states, and the tools include diplomacy, regulation, mega-project finance, and security partnerships.

–

Key Developments, Technologies, and Strategic Principles Shaping Gulf Rivalry

Border and Island Disputes: Why Maps Still Matter to Shipping

Even in a world of satellite AIS and digital port community systems, the legal map remains a foundational maritime document. Territorial disputes influence coast guard authority, marine resource claims, and the political temperature around specific sea areas.

Qatar–Bahrain: Hawar Islands and maritime delimitation

A landmark example of an Arab-state territorial dispute resolved through international adjudication is the Qatar v. Bahrain case at the International Court of Justice, which addressed sovereignty over features including the Hawar Islands and related maritime delimitation questions.

For maritime professionals, the relevance is not historical trivia. It is operational: delimitation outcomes affect enforcement zones and the confidence with which ships, surveyors, and offshore operators plan activities.

Saudi Arabia–UAE: Border history and strategic corridors

Saudi–UAE relations are often described as close, but border history illustrates how strategic geography can generate long-term friction. Publicly discussed background around the 1974 Treaty of Jeddah and later disputes includes issues tied to corridors and resource fields—factors that can matter to infrastructure planning and cross-border logistics narratives.

This is one reason why Gulf rivalry frequently looks “commercial” even when it is geopolitical. Ports, free zones, and industrial corridors are not just economic assets—they are strategic geography converted into revenue.

Competing Models of Regional Influence: From Yemen to Sudan to Libya

Gulf competition is also visible in different alignments and strategies in regional conflicts, which can spill into shipping risk, sanctions exposure, and security costs.

Yemen: Diverging objectives and the maritime security shadow

Yemen matters to maritime trade because it sits near Bab el-Mandeb, a critical gateway connecting the Indian Ocean to the Red Sea and Suez routes. Divergent Saudi and UAE approaches in Yemen have been widely discussed, including differences around local partners and political end-states.

For shipping, the main point is not internal Yemeni politics. The point is that regional rivalry can complicate conflict resolution, and prolonged conflict can amplify maritime security threats, raising insurance costs and encouraging route changes.

Sudan: Rival perceptions, mediation efforts, and reputational risk

Sudan sits on the Red Sea. Instability affects port investment confidence, security provisioning, and—when combined with broader Red Sea tensions—can raise the risk premium for the entire corridor.

Libya and Syria: Competing coalitions and long-term fragmentation effects

Libya has repeatedly drawn in external supporters aligned with different factions. The maritime implication is indirect but real: fragmented states become unstable maritime neighbors, complicating energy exports, migrant flows, and coastal security, which can affect insurance assumptions and regional naval postures.

Energy Competition: Oil Quotas, Gas Fields, and the Politics of Capacity

Energy is still the backbone of Persian Gulf maritime trade—particularly crude and refined product exports, LNG flows, and petrochemical shipping. Competition appears in two main ways: market positioning and production governance.

OPEC+ and the Saudi–UAE quota friction

Disputes within OPEC+ have periodically revealed tensions, including debates about production baselines and the definition of capacity. These episodes matter because they highlight a structural reality: states that invest heavily in production capacity want quotas that monetize that investment, while others prefer tighter supply management for price support.

For maritime operations, oil policy disputes can change tanker demand patterns (more volume vs. managed cuts), affect port congestion risk, reshape storage dynamics, and influence the commercial outlook for bunkering and downstream shipments.

Dorra gas field: contested resources and regional signaling

The Dorra field dispute illustrates how offshore resources can become a diplomatic flashpoint. From a shipping perspective, contested offshore projects can affect offshore service vessel demand, security posture for energy infrastructure, and political risk perception attached to adjacent sea space.

Aviation, Tourism, and the “Hub” Competition: Why Ships Should Care

At first glance, airline rivalry looks separate from maritime trade. In the Gulf, it is not. Aviation hubs and tourism ecosystems often connect to cruise and yachting expansion, high-value air-sea cargo solutions, port city branding, and broader investment attraction.

Riyadh Air and the ambition to challenge Gulf incumbents

Saudi Arabia’s launch of Riyadh Air forms part of a strategy to compete with established regional hubs. Fleet decisions and partnerships signal an attempt to build global connectivity quickly, while Saudi tourism targets support the economic logic behind that airline expansion.

Headquarters rules and the competition for corporate gravity

Competition also includes corporate location rules. Saudi Arabia’s push for regional headquarters aims to shift decision-making gravity toward Riyadh. For maritime clusters—ship management, marine insurance, port finance, classification society offices—where companies base decision-making teams can influence port choices and long-term service networks.

–

Ports, Shipping, and Logistics: The Most Visible Arena of Gulf Competition

If you want to “see” Gulf rivalry, do not start with speeches. Start with container terminals, logistics parks, and industrial zones.

Dubai and DP World: Scale, throughput, and network effects

Dubai’s Jebel Ali remains the benchmark Gulf hub, supported by scale, operational maturity, and a dense logistics ecosystem. Dubai’s advantage is not only cranes and berth length. It is ecosystem density: freight forwarders, free zone services, finance, re-export infrastructure, and a large base of experienced maritime professionals.

Abu Dhabi’s Khalifa Port: capacity growth and carrier partnerships

Abu Dhabi’s strategy leans into industrial integration, modern terminals, and deepening links with global carriers. Capacity expansion announcements and partnerships are designed to position Abu Dhabi as more than a “secondary option,” encouraging liners to treat it as a parallel hub with its own industrial and inland connectivity logic.

Qatar’s Hamad Port: resilience after isolation and a push for transshipment

The 2017–2021 Qatar diplomatic crisis pushed Qatar toward self-reliance and alternative supply chains. That period accelerated port development and diversification. Today, the strategic push is to move beyond a national gateway role and become more relevant in transshipment and regional connectivity.

Saudi Arabia’s logistics bid: Jeddah, zones, and the NEOM/OXAGON storyline

Saudi Arabia is attempting a large repositioning: shifting from a primarily export-energy model to a multi-corridor logistics platform. This includes logistics zones and large-scale partnerships around Red Sea ports, alongside long-term hub ambitions connected to Vision 2030.

Port of NEOM and OXAGON: a “future port” narrative

NEOM’s port strategy is not only about capacity. It is a “future port” narrative: automation, sustainability, and industrial adjacency. The concept is to create a designed-to-be-automated port and industrial cluster, then attract cargo, manufacturers, and global partners into that cluster.

At the same time, NEOM’s trajectory should be assessed in phases. Large mega-projects evolve, and timelines can shift. For maritime stakeholders, the practical approach is to track actual operational milestones, berth readiness, service reliability, and carrier commitments over time rather than relying only on promotional targets.

Oman and the “open gateway” strategy: Duqm and repair capacity

Although Oman’s core coastline is the Arabian Sea rather than the inner Persian Gulf, it is strategically relevant because it offers access that can bypass Hormuz-adjacent concentration and because it is investing in industrial logistics and ship repair ecosystems. For operators, Oman’s value proposition often reads like a risk-management option: additional capacity, alternative routing, and industrial support outside the most politically dense corridors.

–

Maritime Security as the “Multiplier” of Gulf Rivalries

Competition becomes more operationally costly when it interacts with security shocks. The Red Sea crisis showed how quickly regional conflict dynamics can reshape global shipping flows through rerouting, additional insurance costs, and schedule disruption.

For Persian Gulf Arab-state competition, the key insight is this: when rivalry contributes to prolonged instability in adjacent theaters—Yemen being the clearest example—shipping absorbs the cost. That cost appears in insurance, longer voyages, altered schedules, and congestion shifts across global networks.

–

Case Studies / Real-World Applications

Case study 1: “Hub wars” and the carrier planning cycle

Port capacity announcements, new terminal concessions, and logistics-zone incentives are not just infrastructure news; they are signals aimed directly at carriers and global forwarders. When a port presents a credible pathway to faster turnaround and lower total logistics cost, it can influence alliance network planning, transshipment selection, equipment repositioning, and long-term terminal partnerships.

Case study 2: Horn of Africa engagement and port influence

Gulf competition extends beyond Gulf coastlines into the Horn of Africa and Red Sea. Investments and concessions in ports such as Berbera are part of a broader pattern where Gulf states project logistics influence along routes that connect back to Gulf trade. For maritime operators, this matters because it shapes alternative call options, maritime security partnerships, and the commercial geography of the wider region.

–

Future Outlook and Maritime Trends

Dubai is likely to remain a major hub, but the region is becoming multi-hub by design. Abu Dhabi continues to expand and integrate industry with port capability. Qatar continues to build resilience and connectivity. Saudi Arabia is building Red Sea alternatives and positioning new industrial clusters. Oman is strengthening repair and Indian Ocean-facing connectivity.

Meanwhile, automation and “future port” branding will increasingly shape competition. Smart terminals, digital customs, and sustainability-linked operations are becoming part of hub status. In parallel, security volatility is likely to remain priced into trade even during calm periods, meaning rerouting options and resilience planning will remain central to professional shipping strategy.

–

FAQ

1) Are Persian Gulf Arab states truly in conflict with each other, or just competing economically?

Mostly, they compete economically and strategically rather than through open conflict. However, rivalry can become visible through diplomatic disputes, proxy alignments, or policy clashes in energy and regional influence.

2) Which territorial disputes between Gulf Arab states are most relevant historically?

The Qatar–Bahrain case over Hawar Islands and maritime delimitation is a key example of dispute settlement through international adjudication.

3) How does Saudi Arabia’s logistics strategy challenge Dubai’s model?

Saudi Arabia is building logistics zones, expanding Red Sea port capability, and promoting new hubs—alongside investment and corporate policies designed to shift regional gravity.

4) Why do energy policy disagreements matter to shipping?

Because production policy affects tanker demand, voyage patterns, port utilization, storage needs, and the commercial outlook for bunkering and downstream shipments.

5) Is NEOM’s port a real near-term competitor, or a long-term project?

It should be treated as an emerging competitor with phased impact. The operational relevance will grow as terminals become fully functional, services stabilize, and carrier networks commit.

6) What is the biggest security-related factor affecting Gulf-adjacent shipping today?

The interaction between regional conflicts and chokepoints—especially the Red Sea/Bab el-Mandeb corridor—has shown the strongest recent impact through rerouting and risk premiums.

7) How should shipping companies respond to Gulf competition and volatility?

By building flexible networks (multi-hub options), strengthening compliance screening, planning for rerouting, and monitoring policy shifts in logistics zones, port expansions, and security conditions.

–

Conclusion / Take-away

Hidden tensions among Persian Gulf Arab states are not a side story to maritime trade—they are part of the operating environment. Territorial disputes shape legal geography. Proxy competition influences maritime security risk. Energy diplomacy shifts tanker demand. The race to be the region’s primary hub now includes Dubai and Abu Dhabi, but also Qatar’s growing port role and Saudi Arabia’s aggressive logistics strategy connected to Vision 2030 and megaproject narratives such as NEOM.

For maritime professionals, the most useful mindset is practical: treat Gulf competition like a dynamic network market. Plan for multi-hub routing. Monitor infrastructure announcements as strategic signals. Build resilience into contracts and schedules. And when the region looks calm from the horizon, remember that many of the most important changes arrive quietly—through terminals, policies, and partnerships rather than through headlines.

–

References

-

International Court of Justice (ICJ). Maritime Delimitation and Territorial Questions between Qatar and Bahrain (Qatar v. Bahrain).

-

UNCTAD. Review of Maritime Transport 2024.

-

BIMCO. Red Sea security advisories and updates.

-

DP World. Annual and quarterly reporting on port throughput and operations.

-

AD Ports Group / CMA CGM. Khalifa Port terminal expansion announcements.

-

Mwani Qatar. Annual reporting on Hamad Port performance.

-

NEOM. Port of NEOM and OXAGON official pages and updates.

-

SIPRI. Trends in World Military Expenditure (latest edition).

-

International Crisis Group. Sudan conflict analysis and regional implications.