Learn marine incinerator design, capacity sizing, emissions limits, and safety interlocks—plus practical shipboard operating guidance aligned with IMO rules.

On most ships, waste is not a side issue—it is a daily operational reality. Every watch generates oily sludge, packaging, food waste, and maintenance residues. If these streams are not handled correctly, the consequences are immediate: fire risk in the engine room, pollution incidents, port state control (PSC) deficiencies, and reputational damage that can follow a vessel for years.

The marine incinerator sits at the intersection of waste management, engine-room safety, and regulatory compliance. It is not simply a “burner in a box.” It is a controlled combustion system with defined capacity limits, monitoring requirements, and safety interlocks designed to prevent uncontrolled fires, toxic emissions, and illegal disposal. IMO requirements for shipboard incineration are anchored in MARPOL Annex VI, Regulation 16 and associated standard specifications and type approval requirements.

This article explains marine incinerator design and capacity in practical terms, then goes deeper into the safety interlocks that protect people, machinery, and compliance. The emphasis is educational and operational—written for cadets, junior engineers, senior officers who supervise maintenance, and shore teams who specify equipment for newbuilds and retrofits.

When an incinerator is poorly designed, incorrectly sized, or operated outside its limits, it becomes a safety hazard and a compliance trap at the same time. Conversely, a well-specified incinerator with robust interlocks reduces waste storage burdens, lowers fire risk from uncontrolled waste accumulation, and helps ships meet MARPOL requirements under inspection regimes such as port state control.

Key Developments, Principles, and Practical Applications

The regulatory foundation: what “shipboard incineration” is allowed to do

From a compliance perspective, the most important idea is simple: shipboard incineration is allowed only in an approved shipboard incinerator, and certain substances are explicitly prohibited from being burned.

IMO’s Regulation 16 is reinforced by standard specifications adopted by the Marine Environment Protection Committee (MEPC), including a modern standard specification for shipboard incinerators (commonly referenced as the 2014 standard). These specifications support type approval, meaning an incinerator model is tested and certified against IMO requirements, rather than being treated as a generic piece of auxiliary machinery.

A practical way to understand this is to treat the incinerator like a “regulated engine.” It is not only expected to burn waste; it must burn waste within defined combustion conditions, with specific monitoring and safety shut-down logic.

What can and cannot be incinerated onboard

Most operational confusion happens here—particularly with mixed wastes and “special” residues from modern systems.

Regulation 16 prohibits incineration of several waste categories, including (among others) cargo-related wastes covered by MARPOL Annex I/II/III, PCBs, garbage containing heavy metals, certain halogenated refined petroleum products, sewage and sludge oil not generated onboard, and exhaust gas cleaning system residues.

Separately, enforcement guidance used by inspection regimes highlights restrictions such as PVC incineration being prohibited except under specific conditions tied to type approval.

Operationally, the safe approach is to treat waste streams as “fuel specifications.” If the waste composition is unknown, mixed, or contaminated (for example, cleaning rags soaked in solvents, paint residues, or chemical containers), it should not be fed to the incinerator unless the ship’s procedures and the incinerator’s approved operating limits clearly allow it. This approach protects the crew from toxic flue gases and protects the ship from non-compliance.

The modern standard: ISO 13617 and why it matters

In addition to IMO’s MEPC specifications, shipboard incinerators are commonly aligned with ISO 13617, which covers design, manufacture, performance, operation, and testing of shipboard incinerators intended for ship-generated wastes. ISO 13617:2019 applies to incinerator plants up to 4,000 kW per unit, aligning with IMO’s standard specification scope.

For shipowners and shipyards, the practical value of ISO 13617 is that it provides a technical “common language” for procurement, factory acceptance tests, and verification of safety functions beyond marketing claims. For ships’ staff, it indirectly improves reliability because it tightens expectations around combustion performance, controls, and testing.

Understanding incinerator “capacity”: it is not just kg/hour

Many ships describe incinerator capacity in kg/h, but engineers quickly learn that kg/h is only meaningful if the waste has a defined calorific value and moisture content. Sludge oil with emulsified water behaves very differently from dry solid garbage. That is why incinerators are often rated by thermal input (kW or kcal/h) and then mapped to kg/h for different waste categories under test conditions.

Type approval documentation commonly references capacity and test parameters, including maximum capacity (kW/kcal/h) and kg/h of specified waste, with performance measurements taken during type approval.

A helpful analogy is to think of the incinerator like a main engine: the engine has a rated power output, but the fuel consumption depends on fuel quality and operating conditions. Likewise, an incinerator has a rated heat input, but the waste throughput changes depending on moisture content, solids, and how consistently the combustion chamber stays within its required temperature band.

Sizing a marine incinerator: a practical method for ships and newbuilds

Incinerator sizing should begin with the ship’s waste management plan and realistic waste generation rates. The two core drivers are:

-

Oily waste generation (sludge oil, waste lubricants, purifier discharge, tank drainings) driven by engine type, fuel quality, maintenance routines, and voyage length.

-

Solid garbage and domestic waste driven by crew size, catering arrangements, and vessel type (for example, offshore units and passenger vessels create different waste profiles than bulk carriers).

A practical sizing approach used by many technical teams is to calculate “worst-case storage horizon,” then decide whether incineration is intended as the primary reduction tool or a secondary option (with port reception facilities as the primary route). Guidance on ship-generated waste management highlights the role of shipboard practices and regulatory constraints around incineration, emphasizing that it is not a universal solution for all waste types.

When voyages include frequent port calls with reliable reception facilities, a smaller incinerator may be sufficient. When a vessel trades long ocean legs or calls at ports with uncertain facilities, higher incinerator capacity can reduce storage risks—but only if the crew can operate it safely within limits.

Core design architecture: what is inside a marine incinerator system

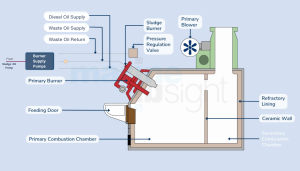

Most marine incinerator plants consist of:

-

A combustion chamber (often refractory-lined) designed to maintain stable high temperatures.

-

One or more burners (pilot and main) typically using marine diesel oil (MDO) or similar fuel for start-up and stability.

-

A waste oil/sludge injection system (for oily waste capable units), typically with filtration, heating, and controlled atomisation.

-

A solid waste charging arrangement, either batch-loaded (door-fed) or continuous-feed (ram feeder/screw).

-

A combustion air fan and air distribution system to ensure mixing and adequate oxygen.

-

A flue gas uptake with temperature measurement points, and sometimes a dedicated exhaust fan/damper arrangement.

-

A control system (PLC-based in many modern systems), which is where safety interlocks live.

In practical terms, the hardware provides the ability to burn, but the control system provides the ability to burn legally and safely.

Operating temperature and combustion control: why 850°C is more than a number

Regulation 16 sets operating requirements that connect directly to safety interlocks. One widely cited requirement is that waste must not be fed into a continuous-feed incinerator when the combustion temperature is below a minimum, and that flue gas outlet temperature monitoring is required. Guidance commonly references a minimum of 850°C for continuous feed, and design expectations for batch-loaded incinerators reaching 600°C within five minutes after start-up.

These temperatures matter because incomplete combustion produces higher levels of CO and unburned hydrocarbons and increases the risk of soot deposits. In engine-room reality, soot is not a cosmetic issue—it is fuel for a secondary fire in the uptake system if temperatures spike.

Emissions and performance limits: what type approval testing looks at

Specifications require type approval tests to measure key parameters and confirm the unit meets an emission standard within defined conditions.

Operating limits for shipboard incinerators are often defined in appendices, covering combustion conditions (such as oxygen range) and pollutant limits (such as CO), alongside test waste compositions (including mixtures with significant moisture and incombustibles).

For ship staff, the practical implication is that the incinerator is approved only when operated in its intended window. If the crew consistently runs it too cold, overloads it with wet waste, or bypasses interlocks, the vessel is effectively operating outside its certified performance envelope—a risk under inspection and a risk to onboard safety.

Credit: Marineinsight

Safety Interlocks: The Heart of Safe Marine Incineration

Safety interlocks are not optional conveniences. They are engineered barriers that prevent predictable accident scenarios. The most useful way to understand interlocks is to link them to the failure modes they prevent.

Flame failure and burner safety interlocks

A marine incinerator typically has a pilot flame and a main flame. Flame failure interlocks monitor flame presence via flame sensors and shut down fuel supply if flame is lost. This prevents unburned fuel from accumulating in the chamber, which could lead to an explosive ignition (a “puff back”) when the flame re-establishes.

In practical shipboard terms, flame failure interlocks protect against sudden loss of combustion air (fan trip), fuel pressure fluctuation, atomisation failure (steam/air issues), and refractory cold start conditions.

Low-temperature cut-outs and waste feed permissives

Temperature-based permissives are among the most important compliance-linked interlocks. If the combustion chamber or flue gas outlet temperature is below the required minimum, continuous waste feeding must stop.

This interlock prevents cold, smoky burning and reduces soot formation. Operationally, it also forces the crew to treat start-up as a controlled sequence: stabilize temperature first, then begin feeding waste.

Combustion air and draft interlocks

Incineration is a controlled oxidation process. Without stable air supply and draft, combustion becomes unstable and dangerous. Air fan failure, damper malfunction, or blocked uptake can produce backflow, smoke release into the machinery space, or high CO conditions.

Draft and fan interlocks typically ensure the combustion air fan is running and within expected parameters, dampers are in the correct position, and pressure conditions in the chamber are within safe bounds.

A simple analogy is the forced-draft system of a boiler: you do not introduce fuel unless you have confirmed air flow and purging logic, because the combination of fuel without air creates explosive potential.

Door safety interlocks for batch-loaded incinerators

Batch-loaded incinerators include an access door or charging door. Door interlocks prevent the door from opening during unsafe conditions and/or prevent firing when the door is open. This protects against flashback and protects crew from radiant heat and flame exposure.

In shipboard reality, door interlocks also reduce the temptation to “quickly add something” mid-cycle—one of the most common behavioural risks in waste-burning operations.

Sludge oil system interlocks: viscosity, heating, and atomisation

Incinerators that burn oily sludge require controlled heating and atomisation. Interlocks often monitor sludge oil temperature (to ensure pumpability and atomisation), fuel/atomising medium availability (steam or compressed air), pump pressure and flow, and filter differential pressure (to detect blockage).

These interlocks reduce the risk of “liquid pooling” in the chamber, which can cause sudden flare-ups or unstable burning that damages refractory lining.

Overtemperature protection and refractory safeguarding

Overtemperature interlocks protect the incinerator structure and surrounding engine-room environment. An overtemperature condition may indicate excess fuel input, air/fuel imbalance, door leakage, or excessively dry/high-calorific waste load.

Overtemperature trip logic is a safety barrier against equipment damage and uptake fires. It is also a maintenance cost control: refractory damage can be expensive and can take the incinerator out of service for extended periods.

Emergency stop logic and safe shutdown sequencing

A robust incinerator control system executes a controlled shutdown sequence on trip conditions: stop waste feed, close fuel valves, continue post-purge air flow, and prevent immediate restart until conditions are verified.

The value of sequencing is often underestimated. An uncontrolled shutdown can leave combustible material smouldering without airflow, producing smoke and toxic gases that may later ignite unpredictably.

Challenges and Practical Solutions

The most common incinerator failures at sea are not “mystery technical faults.” They are predictable outcomes of three practical issues: waste variability, poor maintenance discipline, and procedural shortcuts.

When waste is wet or mixed, crews may overload the incinerator to “catch up,” causing low-temperature smoking, soot build-up, and eventual flame failure trips. The practical solution is to treat incineration like engine operation: feed rate must match combustion stability. Segregating waste at source and using smaller, consistent batches stabilizes performance and reduces alarms.

Maintenance discipline matters because incinerators operate in harsh conditions—heat cycling, soot, corrosive ash, and vibration. Temperature sensors drift, dampers seize, burner nozzles foul, and door seals degrade. The practical solution is to integrate incinerator checks into the planned maintenance system with specific acceptance criteria, not vague “inspect and clean” routines.

Finally, procedural shortcuts—such as bypassing interlocks or overriding trips—are often rooted in operational pressure. The practical solution is managerial: align waste management planning with voyage schedules and port reception arrangements so the crew is not forced into unsafe time-compression behaviour.

Case Studies and Real-World Applications

A common scenario on long-haul bulk carriers is sludge accumulation during extended periods of heavy fuel operation, particularly when purifier settings are conservative or fuel quality is poor. The incinerator becomes the primary disposal route. If the incinerator capacity is underspecified or the crew lacks time to run it within stable temperature limits, sludge tanks approach high levels and operational risk increases. In these cases, ships that combine disciplined sludge handling (settling, dewatering where possible, controlled feed rates) with strict adherence to temperature permissives generally experience fewer incinerator trips and fewer maintenance issues.

Another real-world trend is the appearance of new waste categories from modern compliance systems. Exhaust gas cleaning system residues, for example, are treated as prohibited for incineration under Regulation 16, meaning ships must rely on approved landing arrangements rather than onboard burning.

This is why incinerator operation must be embedded in the ship’s full waste governance system—garbage management planning, recordkeeping, and port interface—not treated as an isolated engine-room task.

Future Outlook and Maritime Trends

Incinerators are unlikely to disappear, but their role is changing. Stronger waste-delivery enforcement, expanding port reception infrastructure, and tighter scrutiny under inspection regimes reduce the tolerance for informal waste practices. Inspection guidance addressing MARPOL Annex VI indicates that inspectors are equipped to check both documentation and operational compliance.

Technically, future incinerator systems are likely to feature more robust automation, improved combustion monitoring, and clearer digital audit trails (alarms, trips, temperature histories) that support both maintenance diagnostics and compliance evidence. Procurement alignment with ISO 13617 and IMO type approval expectations will remain central for newbuilds and major retrofits.

FAQ

1) What is the main IMO rule for marine incinerators?

Shipboard incineration is generally permitted only in an approved shipboard incinerator and must comply with MARPOL Annex VI, Regulation 16 and related specifications and type approval requirements.

2) Can a ship burn any garbage in the incinerator?

No. Several substances are prohibited, including PCBs, certain halogenated petroleum products, garbage containing heavy metals, and exhaust gas cleaning system residues, among others.

3) Why is the 850°C requirement important?

It ensures stable, complete combustion and limits smoke, soot formation, and high CO conditions. Continuous-feed incinerators must not be fed when temperature is below the minimum allowed level, and temperature monitoring is required.

4) What does “IMO type approval” mean for an incinerator?

It means a specific incinerator model has been tested under defined conditions and certified by an Administration against IMO standard specifications.

5) How do I know if an incinerator is correctly sized?

Sizing should match shipboard waste generation (oily waste and solids), voyage patterns, and availability of port reception facilities, while ensuring the incinerator can operate stably within certified limits.

6) What are the most critical safety interlocks?

Flame failure trip, low-temperature waste-feed permissive, combustion air/draft interlocks, and door safety interlocks (for batch units) are among the most safety-critical barriers because they prevent fuel accumulation, cold smoking, backflow, and flashback hazards.

7) Can PVC be incinerated onboard?

Inspection and enforcement guidance generally treat PVC incineration as prohibited, with limited exceptions tied to type approval certification and compliance conditions. In practice, ships should follow their approved procedures and the incinerator’s certified operating limits.

Conclusion and Take-Away

A marine incinerator is not waste disposal equipment in the casual sense. It is a controlled combustion plant governed by MARPOL Annex VI requirements, verified through type approval, and made safe through interlocks that prevent predictable accident scenarios. Design and capacity must be matched to real waste profiles, not optimistic assumptions. Operation must stay inside certified temperature and feed conditions, not only to satisfy inspectors, but to avoid soot fires, toxic smoke, refractory damage, and dangerous flare-ups.

For ship operators and maritime students, the practical takeaway is straightforward: treat incinerator operation like any other safety-critical machinery. Respect the interlocks, stabilize combustion before feeding, segregate waste rigorously, and integrate incineration into the ship’s broader waste governance system. If you do that consistently, the incinerator becomes a compliance-supporting tool rather than a recurring casualty report waiting to happen.

References

-

International Maritime Organization (IMO). Shipboard incineration – Regulation 16.

-

IMO. Resolution MEPC.244(66): 2014 Standard Specification for Shipboard Incinerators (PDF).

-

IMO. Resolution MEPC.76(40): Standard Specification for Shipboard Incinerators (PDF).

-

ISO. ISO 13617:2019 — Shipboard incinerators — Requirements (standard overview).

-

EMSA. The Management of Ship-Generated Waste On-board Ships (guidance PDF).

-

Paris MoU. Guidelines on MARPOL Annex VI (includes Regulation 16 inspection guidance) (PDF).

-

REMPEC. MARPOL Annex VI – Prevention of Air Pollution from Ships (includes Regulation 16 summary) (PDF).