Airports and Ports as a Single Transport System

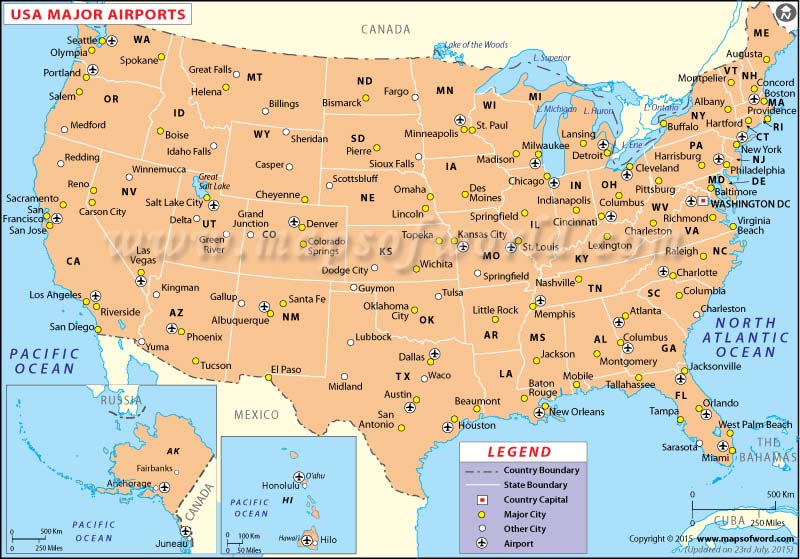

In the modern United States transportation landscape, airports and seaports increasingly function not as isolated infrastructures but as interdependent nodes within integrated multimodal systems. This interconnection is especially visible among the Top 50 U.S. airports by passenger traffic in 2019, the last full year before COVID-19 disrupted global mobility patterns.

While airports are commonly perceived as gateways for passengers and high-value air cargo, and ports as gateways for bulk commodities and containerized trade, the reality is far more interconnected. Many of the busiest U.S. airports are physically, economically, and operationally linked to major ports, enabling air–sea cargo transfers, cruise passenger flows, maritime crew mobility, offshore energy logistics, and military operations.

This article explains which of the major U.S. airports are linked to ports, the nature of those linkages, and why they matter for trade, tourism, and national logistics resilience.

What Does “Air–Sea Connectivity” Really Mean?

Air–sea connectivity does not imply that aircraft land on ships or that cargo is routinely transferred directly from planes to vessels. Instead, it refers to functional integration, typically supported by road, rail, digital systems, and institutional coordination.

In practice, air–sea connectivity takes several forms:

-

Cargo complementarity, where ports handle bulk and containers while airports manage time-critical, high-value, or perishable goods

-

Passenger transfer ecosystems, particularly in cruise tourism, where airports act as global feeders to seaports

-

Industrial and offshore logistics, supporting energy, ship repair, fisheries, and naval activities

-

Strategic resilience, allowing supply chains to shift between modes during disruptions

The strongest air–sea linkages tend to occur in coastal metropolitan regions, where geography, population density, and economic specialization reinforce each other.

West Coast Gateways: Airports Embedded in Global Maritime Trade

Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) and the Southern California Port Complex

LAX is one of the most important aviation hubs in the world, but its strategic value cannot be understood without reference to its proximity to the Port of Los Angeles and the Port of Long Beach. Together, these ports form the largest container gateway in the Western Hemisphere, handling a substantial share of U.S.–Asia trade.

The airport and ports operate as complementary logistics platforms. High-value electronics, medical devices, fashion goods, and aerospace components often arrive by air at LAX, while bulkier and less time-sensitive goods move through the ports. Conversely, delays or congestion at the ports frequently increase demand for air freight as an alternative.

LAX also supports maritime operations in less visible but equally important ways. Shipping executives, port engineers, seafarers, and inspectors regularly transit through the airport. In addition, cruise passengers embarking from terminals in San Pedro and Long Beach often arrive internationally via LAX.

Seattle-Tacoma International Airport (SEA) and the Port of Seattle

The Seattle region offers one of the most institutionally integrated air–sea systems in the United States. The Port of Seattle manages both the airport and the seaport, enabling coordinated planning across aviation, maritime trade, and cruise operations.

SEA supports containerized trade with East Asia, but its most visible passenger linkage is with Alaska cruise tourism. Each summer season, hundreds of thousands of cruise passengers fly into Seattle before embarking on voyages to Alaska. At the same time, the airport handles seafood exports and time-critical logistics linked to the fishing industry.

This integrated governance model allows Seattle to align environmental targets, infrastructure investments, and digital systems across both modes.

San Francisco International Airport (SFO) and the Port of Oakland

Although SFO is not immediately adjacent to a major cruise terminal, it plays a critical role in air–sea cargo complementarity with the Port of Oakland. The Bay Area economy is dominated by technology, biotechnology, and advanced manufacturing, sectors that rely heavily on fast and reliable air cargo.

Semiconductors, laboratory equipment, pharmaceuticals, and high-value prototypes often move by air through SFO, while larger production volumes and raw materials pass through Oakland’s container terminals. Together, they form a dual-mode logistics system supporting Silicon Valley and Northern California’s global trade links.

Gulf Coast and Energy-Driven Air–Sea Connectivity

Houston George Bush Intercontinental Airport (IAH) and the Port of Houston

Houston represents a different model of air–sea connectivity, one driven less by consumer goods and tourism and more by energy and industrial logistics. The Port of Houston is a leading hub for petrochemicals, refined products, and project cargo, while IAH functions as an international gateway for energy professionals.

The airport supports offshore oil and gas operations by enabling rapid movement of engineers, technicians, and executives. Specialized equipment and urgent spare parts often move by air, complementing the port’s heavy-lift and bulk cargo capabilities. Although cruise tourism plays only a minor role, the industrial air–sea linkage is strategically significant for the U.S. energy sector.

Tampa International Airport (TPA) and Port Tampa Bay

Tampa offers a hybrid model combining cruise tourism, regional trade, and limited bulk cargo operations. Port Tampa Bay supports cruise lines serving the Caribbean, while TPA handles passenger flows and aviation-related logistics. Although smaller in scale than Miami or Fort Lauderdale, Tampa illustrates how mid-tier airports can still play a meaningful role in maritime passenger systems.

Florida: The Epicenter of Airport–Cruise Port Integration

Miami International Airport (MIA) and PortMiami

Miami is arguably the most tightly coupled airport–port system in the United States. PortMiami is the world’s leading cruise port, while MIA serves as its primary global feeder.

On peak cruise days, tens of thousands of passengers move between the airport and port within a matter of hours. This requires coordinated scheduling, customs processing, baggage handling, and ground transport logistics. Beyond tourism, Miami also functions as a key air–sea cargo hub for Latin America, particularly for perishables such as flowers, seafood, and pharmaceuticals.

Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport (FLL) and Port Everglades

FLL’s proximity to Port Everglades makes it one of the most efficient fly-cruise transfer hubs in North America. Many cruise passengers can move from aircraft to ship in less than an hour, a factor that has driven the port’s popularity with major cruise lines.

The airport also supports maritime fuel supply logistics and limited container traffic, reinforcing its role as a multifunctional transport node.

Orlando International Airport (MCO) and Port Canaveral

Although inland, MCO is one of the most important cruise-linked airports in the country. Port Canaveral relies heavily on Orlando’s air connectivity, particularly for international cruise passengers combining theme parks with sea travel. This demonstrates that physical proximity is not always required for functional air–sea integration.

The Northeast: Cargo Density and Consumer Markets

Newark Liberty International Airport (EWR) and the Port of New York and New Jersey

The Port of New York and New Jersey serves the largest consumer market in the United States, and EWR plays a central role in supporting this trade. High-value imports such as fashion goods, electronics, and pharmaceuticals often arrive by air before being distributed through the same logistics networks that handle maritime containers.

Although cruise operations are more prominent in nearby Manhattan and Brooklyn terminals, Newark’s cargo function makes it a critical air–sea logistics interface.

Hawaii: A Special Case of Total Air–Sea Dependence

Daniel K. Inouye International Airport (HNL) and the Port of Honolulu

Hawaii represents a unique case where air and sea transport are inseparable. Nearly all goods consumed in the islands arrive by sea, while nearly all people arrive by air. The Port of Honolulu handles containerized supplies, fuel, and inter-island shipping, while HNL supports tourism, military mobility, and high-value cargo.

Cruise passengers, inter-island travelers, and maritime workers all rely on this tightly integrated system, making Honolulu one of the clearest examples of systemic air–sea interdependence.

Airports with Minimal or Indirect Port Linkages

Not all top airports have meaningful maritime connections. Inland hubs such as Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport, Denver International Airport, and Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport focus primarily on air-to-air and air-to-land connectivity.

However, even these airports indirectly support port systems through inland distribution centers, rail corridors, and national supply chains, highlighting that air–sea integration can be direct or systemic.

Why Air–Sea Connectivity Matters More Than Ever

As global logistics face increasing pressure from climate change, geopolitical tension, and demand volatility, the ability to shift flows between air and sea modes becomes a critical resilience strategy. Integrated airport–port regions can:

-

Absorb shocks such as port congestion or shipping delays

-

Support cruise tourism recovery and growth

-

Enable faster decarbonization through coordinated planning

-

Strengthen national supply chain security

Conclusion

Among the Top 50 U.S. airports in 2019, a substantial number are deeply linked to nearby ports for either cargo movement, passenger transfer, or industrial logistics. Airports such as Los Angeles, Miami, Seattle, Houston, Newark, and Honolulu function not merely as aviation hubs, but as core components of maritime-centric transport ecosystems.

Understanding these linkages is essential for policymakers, port authorities, transport planners, and maritime professionals seeking to design efficient, resilient, and sustainable transport networks in the decades ahead.