Three marginal seas on the western edge of the Pacific—the Yellow Sea, East China Sea, and South China Sea—shape the daily realities of global maritime trade, naval strategy, energy security, fisheries, and international law. Together, they form a maritime corridor that links Northeast Asia’s industrial heartlands to Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean, and onward to Europe and Africa. More than any other ocean region, this tri-sea system concentrates shipping density, port capacity, contested sovereignty claims, and the intersection of great-power interests.

For seafarers and port professionals, these seas are operational spaces governed by traffic separation schemes, port state control regimes, weather systems, and safety rules. For policymakers and strategists, they are geopolitical theatres where legal interpretations of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) meet naval deployments and diplomacy. For energy markets, they are arteries for oil, LNG, coal, and refined products. For coastal communities, they are sources of food, livelihoods, and environmental risk.

This article explains why these seas matter—individually and collectively—through a maritime lens that balances professional accuracy with accessible language. It traces geography and trade, explains legal frameworks, unpacks geopolitical tensions, and connects them to practical implications for shipping operations and future maritime trends.

Why This Topic Matters for Maritime Operations

The Yellow Sea, East China Sea, and South China Sea are not abstract geopolitical concepts; they are lived operational environments. Every day, thousands of vessels—container ships, bulk carriers, tankers, LNG carriers, ferries, fishing vessels, and naval units—share constrained sea space close to busy coastlines. Navigation occurs amid dense traffic, seasonal fog, typhoons, shallow bathymetry, and extensive fishing activity. In such conditions, safety margins are thin, and regulatory clarity matters.

From an operational standpoint, these seas host some of the world’s largest ports and shipbuilding clusters. Chinese, Korean, and Japanese ports dominate global throughput rankings, while Southeast Asian hubs function as transshipment pivots. Delays or disruptions in these waters propagate instantly across global supply chains, affecting freight rates, insurance premiums, and delivery schedules worldwide.

Equally important is governance. Port State Control regimes, vessel traffic services, and regional cooperation mechanisms influence compliance with international conventions developed by bodies such as the International Maritime Organization. When political tensions rise, compliance and cooperation can suffer, increasing uncertainty for operators.

Finally, these seas are where maritime law, naval presence, and commercial shipping coexist. The coexistence is uneasy but unavoidable. Understanding it is essential for shipowners, masters, maritime educators, and policymakers alike.

Geographic and Maritime Overview of the Three Seas

The Yellow Sea: Gateway Between China and Korea

The Yellow Sea lies between mainland China and the Korean Peninsula. Shallow and semi-enclosed, it receives large sediment loads from major rivers, especially the Yellow River. These sediments create extensive mudflats and shifting seabeds that complicate navigation and dredging. Seasonal fog and winter ice in northern areas further challenge operations.

From a geopolitical perspective, the Yellow Sea is relatively less contentious than its southern counterparts, yet it remains strategically sensitive. It hosts key Chinese naval bases and lies adjacent to the Korean Peninsula, where regional security dynamics directly influence maritime traffic. Commercially, it serves as the maritime forecourt for ports such as Qingdao, Tianjin, and Incheon, connecting heavy industry, agriculture, and energy imports to inland markets.

The East China Sea: Energy, Islands, and Strategic Depth

The East China Sea stretches between China, Japan, and Taiwan. It is deeper than the Yellow Sea and serves as a critical conduit between Northeast Asia and the wider Pacific. Rich fishing grounds and potential hydrocarbon reserves heighten its economic value.

The sea is also home to contested island groups, most notably the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. These disputes are not merely symbolic; they influence Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) claims and access to resources. For shipping, the East China Sea is a high-traffic zone where commercial routes intersect with naval patrols and air defense identification zones, requiring heightened situational awareness.

The South China Sea: The World’s Maritime Crossroads

The South China Sea is the most geopolitically charged of the three. Bordered by China, Taiwan, Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, and Indonesia, it connects the Pacific and Indian Oceans through chokepoints such as the Malacca, Sunda, and Lombok Straits. Roughly one-third of global maritime trade by volume transits this sea annually, including a substantial share of global energy shipments.

Its geography includes hundreds of reefs, shoals, and small islands, many of which have been reclaimed or militarized. These features complicate navigation and raise the stakes of legal interpretation under UNCLOS. For the maritime industry, the South China Sea represents both opportunity and risk: opportunity through connectivity and risk through potential conflict or regulatory fragmentation.

Legal Frameworks and Maritime Governance

UNCLOS and the Law of the Sea

At the heart of maritime governance in these regions lies UNCLOS, which defines territorial seas, EEZs, and continental shelves. While all coastal states reference UNCLOS, interpretations differ. Disagreements arise over historic rights, island status, and permissible activities within EEZs, especially regarding military operations and resource exploration.

For commercial shipping, freedom of navigation is paramount. UNCLOS enshrines transit passage through international straits and innocent passage through territorial seas. Yet, when states adopt expansive interpretations, uncertainty emerges. This uncertainty can translate into operational risk assessments, routing decisions, and insurance considerations.

Arbitration and Enforcement

The 2016 arbitral ruling in a case brought by the Philippines clarified several legal points regarding maritime features and historic claims in the South China Sea. While legally binding on the parties, its political acceptance remains contested. The gap between legal clarity and political reality illustrates a broader challenge: international maritime law depends on state consent and enforcement.

Classification societies such as Lloyd’s Register, DNV, and American Bureau of Shipping play indirect but vital roles by ensuring ships comply with safety and environmental standards regardless of where they sail. Their technical neutrality helps stabilize operations amid political tension.

Geopolitics and Power Dynamics

Great Powers and Regional Actors

China, Japan, and South Korea dominate the Yellow and East China Seas economically, while Southeast Asian states shape the southern theater. The United States, although not a coastal state, maintains a significant naval presence to support freedom of navigation and alliance commitments. This presence influences regional behavior and reassurance dynamics.

Naval deployments coexist with merchant shipping, often operating in close proximity. Exercises, patrols, and surveillance activities can temporarily disrupt traffic patterns. For masters and operators, understanding Notices to Mariners and regional advisories issued by authorities such as the United States Coast Guard is essential.

Energy Security and Sea Lines of Communication

Energy flows underpin much of the geopolitics in these seas. Oil and LNG shipments from the Middle East and Australia transit the South China Sea en route to Northeast Asia. Any perceived threat to these sea lines of communication triggers strategic concern and contingency planning.

This energy dependence explains why maritime security initiatives and regional dialogues persist despite political rivalry. Even competing states share an interest in keeping shipping lanes open, highlighting a pragmatic layer beneath geopolitical competition.

Environmental Pressures and Sustainability

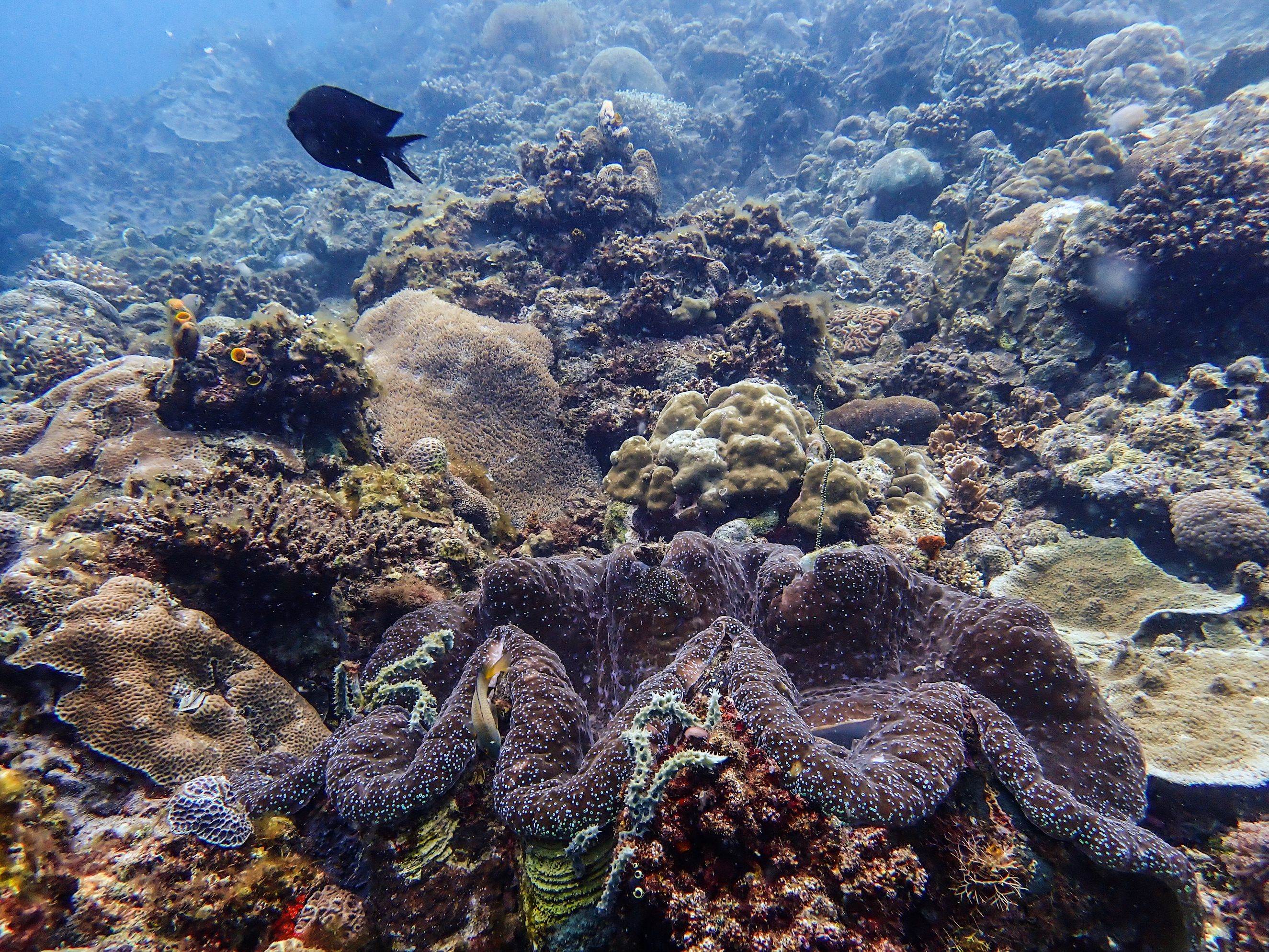

The environmental dimension of these seas is often overshadowed by geopolitics, yet it is equally critical. Overfishing, coastal development, pollution, and climate change stress marine ecosystems. Coral reefs in the South China Sea, for example, are biodiversity hotspots that also act as natural breakwaters and fish nurseries.

International cooperation on environmental protection is uneven. Regional bodies and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development increasingly link sustainable shipping practices with economic resilience. For ship operators, compliance with MARPOL and emerging decarbonisation measures is not optional; it is part of maintaining a social license to operate in sensitive waters.

Challenges and Practical Solutions for Shipping

Operating in these seas requires adaptive risk management. Challenges include dense traffic, overlapping jurisdictional claims, and variable enforcement practices. Practical solutions lie in enhanced bridge resource management, real-time traffic monitoring, and adherence to internationally recognized standards.

Digital tools such as AIS-based platforms from MarineTraffic and transparency databases like Equasis support situational awareness and due diligence. At the institutional level, cooperation through regional port state control regimes and information sharing mitigates fragmentation.

Case Studies and Real-World Applications

Container Shipping Through the South China Sea

Major liner services connecting East Asia to Europe routinely traverse the South China Sea. When tensions rise, operators rarely reroute because alternatives are longer and costlier. Instead, they enhance monitoring and communication, illustrating how commercial imperatives and geopolitical realities intersect.

Fisheries Management in the East China Sea

Competing fishing fleets and declining stocks have prompted bilateral and multilateral management efforts. While imperfect, these arrangements demonstrate that cooperation is possible even amid sovereignty disputes, offering lessons for broader maritime governance.

Future Outlook and Maritime Trends

Looking ahead, the importance of these seas will grow rather than diminish. Asia’s economic center of gravity continues to shift seaward, increasing port capacity, shipbuilding output, and maritime services. At the same time, decarbonisation pressures will reshape vessel design, fuel choices, and port infrastructure.

Geopolitically, competition is likely to persist, but outright conflict remains unlikely because of mutual economic dependence. The challenge for the maritime sector will be to operate safely and efficiently in an environment where legal clarity, political trust, and environmental stewardship do not always align.

FAQ

Why is the South China Sea so important for global trade?

Because it carries a large share of world maritime trade, including critical energy shipments linking the Pacific and Indian Oceans.

Are the Yellow and East China Seas also contested?

Yes, particularly the East China Sea, where island disputes affect EEZ claims and resource access.

Does UNCLOS resolve all disputes?

UNCLOS provides a framework, but enforcement depends on political acceptance and cooperation.

How do geopolitical tensions affect seafarers?

They increase the need for situational awareness, compliance with advisories, and robust safety management.

Is environmental protection improving in these seas?

Progress is uneven, but international pressure and industry standards are driving gradual improvements.

Can shipping avoid these regions?

In most cases, no. They are central corridors with no practical large-scale alternatives.

Conclusion

The Yellow Sea, East China Sea, and South China Sea are more than regional waters; they are pillars of the global maritime system. Their importance lies in the convergence of trade, energy, law, and power. For maritime professionals and learners, understanding these seas is essential to navigating both charts and geopolitics. As the maritime industry faces an era of transformation, informed engagement with these regions will remain a core competency.

References

International Maritime Organization. (https://www.imo.org)

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. (https://www.un.org/depts/los)

UNCTAD Review of Maritime Transport. (https://unctad.org)

Lloyd’s List Intelligence. (https://lloydslist.maritimeintelligence.informa.com)

Marine Policy Journal (Elsevier). (https://www.journals.elsevier.com/marine-policy)

MarineTraffic. (https://www.marinetraffic.com)

Equasis. (https://www.equasis.org)