Discover what a seaport truly is: the vital hub of global trade. This guide explains seaport definitions, types (container, bulk, passenger), functions, modern challenges, and future trends shaping maritime commerce.

A seaport is a complex, coordinated interface where land and sea transport systems meet to move over 80% of global trade by volume. More than just a dock or a terminal, a modern seaport is a sophisticated economic engine, a logistical chessboard, and a community of interconnected services working in unison. From the mega-hubs of Shanghai and Rotterdam handling millions of containers to specialized ports managing liquid gas or cruise passengers, seaports are the critical nodes in the supply chains that power our world. This article delves into the anatomy of these vital facilities, explaining their core definition, categorizing their diverse types, and unpacking their essential functions. We will explore how ports have evolved from simple harbors into smart, integrated logistics centers, facing down modern challenges like cybersecurity threats and geopolitical tensions, while navigating a future shaped by automation and decarbonization. Understanding seaports is fundamental to understanding global commerce itself.

What is a Seaport?

The seaport has a long history going back to the early days of human endeavors. As soon as civilizations emerged across the world, maritime trade networks supported by ports emerged as well. Although maritime transport technology has evolved substantially, the role and function of ports remain relatively similar. Conventionally, a port is defined as a transit area, a gateway through which goods and people move from and to the sea. It is a place of contact between the land and maritime space, a node where ocean and inland transport systems interact, and a place of convergence for different transportation modes. Since maritime and inland transportation modes have different capacities, the port assumes the role of a point of load break where cargo is stored, consolidated, or deconsolidated.

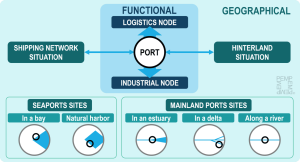

Even if the term port appears generic, it expresses a substantial diversity of sizes and functions. Ports also have a geographical diversity in terms of the sites being used for port activities, which can range from rivers and bays to offshore locations. They are complex and multi-faceted and can be approached primarily from a supply chain perspective, which leads to the following definition:

A seaport is a logistic and industrial node in global supply chains with a strong maritime character and a functional and spatial clustering of activities linked to transportation, transformation, and distribution. It acts as an interface between maritime and inland systems of circulation.

A modern seaport is not regarded solely as a load breakpoint in various supply chains but should be considered a value-adding transit point. As nodes within transportation and logistics networks, ports have a location, whose relative importance can fluctuate given economic, technical, and political changes. This location tries to capitalize on the advantages of a port site characterized by fundamental physical features influencing the nautical profile, such as tides, water depth, access channels, and available land. The nautical profile coordinates the setting of the major physical elements that constitute a port, including navigation channels, turning basins, berthing basins, berths, piers, and jetties.

The seaport is one element within the maritime industry, which involves all the activities enabling and supporting maritime shipping. It includes the shipping industry, such as carriers and shipowners, the port industry, such as port authorities and terminal operators, the management and oversight of cargo and ancillary activities, such as finance, insurance, and bunkering. The industry relies on fundamentals linked to its derived demand, capital intensity, and economies of scale.

Defining the Seaport

Defining the Modern Seaport: Beyond the Dock

At its simplest, a seaport is a location on a coast or shore containing one or more harbors where ships can dock to transfer people and cargo to and from land. However, this basic definition fails to capture the scale and complexity of the modern port. Today, a seaport is best understood as a multi-functional logistics platform and a vital link in global transport networks.

A port’s physical anatomy typically includes several key components. The waterfront features berths and terminals—specialized docking areas designed for specific ship and cargo types, such as container gantry cranes or bulk conveyor systems. Landside, the port area encompasses extensive back-up areas, storage yards (for containers, vehicles, or commodities), warehouses, cargo assembly facilities, and intermodal transfer points where cargo moves between ships, trucks, and trains. Critically, a port is also defined by its landward connections—the roads, railways, pipelines, and inland waterways that connect it to hinterlands and consumer markets, often stretching hundreds of miles inland.

Legally and administratively, a port is a zone of defined authority. The port authority is the governing body that manages the infrastructure, coordinates terminal operators, ensures safety and security compliance, and plans long-term development. This authority operates within national and international legal frameworks, making the port a space where sovereignty, commerce, and global standards intersect.

Key Types of Seaports: Specialization in a Global Network

Seaports are not monolithic; they specialize based on the cargo they handle, their geographical role, and the services they provide. This specialization allows for greater efficiency and scale in the global shipping network.

Classification by Primary Cargo Type

The most common way to categorize ports is by their dominant cargo, which dictates their design and equipment.

-

Container Ports: These are the giants of global trade, handling standardized steel boxes. They are characterized by vast yards, massive ship-to-shore gantry cranes, and complex IT systems to track each container. Ports like Singapore and Shenzhen are archetypes. Their function is the rapid transshipment of containers between deep-sea vessels and feeder ships or land transport.

-

Bulk Carrier Ports: These ports handle loose, unpackaged commodities. They split into two sub-types:

-

Dry Bulk Ports: For commodities like iron ore, coal, and grain. They feature large storage silos or open stockpiles and specialized equipment such as cantilevered shiploaders and continuous conveyor systems.

-

Liquid Bulk Ports: For crude oil, refined petroleum products, and liquefied natural gas (LNG). These ports have tanker berths connected to subsea pipelines and onshore storage tanks, with strict safety zones due to the hazardous nature of the cargo.

-

-

Roll-on/Roll-off (Ro-Ro) Ports: Designed for wheeled cargo, these ports have large ramps for vehicles to drive directly on and off specialized ships. They are crucial for the automotive trade and for ferry services carrying trucks and passengers.

-

General Cargo and Multi-Purpose Ports: These handle non-containerized, packaged goods (break-bulk) like timber, steel coils, or project cargo (e.g., wind turbine blades). They use mobile cranes and have flexible storage areas. While less dominant than container ports, they remain vital for specific trades and regions.

-

Passenger Ports (Cruise and Ferry): Focused on people rather than cargo, these ports prioritize passenger terminals with amenities like check-in halls, baggage handling, customs, and direct links to tourist infrastructure.

Classification by Function and Position in the Supply Chain

Beyond cargo, ports play different logistical roles:

-

Gateway Ports: These serve a vast local or national hinterland, acting as the primary entry and exit point for a country’s imports and exports. The Port of Los Angeles is a classic gateway for the United States.

-

Transshipment Hubs: These ports, like Colombo or Gioia Tauro, specialize in transferring containers from large, long-distance “mother ships” onto smaller “feeder” vessels that serve regional gateway ports. Their success depends on strategic location on major shipping lanes and ultra-efficient operations.

-

Inland Ports (Dry Ports): Not coastal, these are inland intermodal terminals connected to seaports by rail or barge. They extend the seaport’s reach, allowing for cargo consolidation, customs clearance, and distribution far inland, relieving congestion at the coastal waterfront.

–

The Core Functions of a Seaport: More Than Loading and Unloading

The fundamental operation of a port is cargo transfer, but this simple concept belies a symphony of coordinated functions that ensure speed, safety, and security.

Cargo Handling and Intermodal Transfer is the physical heart of port operations. It involves the synchronized movement of goods from the ship’s hold to land transport. This requires specialized equipment—from container cranes and bulk unloaders to forklifts and terminal tractors—operated by skilled personnel. The efficiency of this transfer, measured in moves per hour for containers or tons per hour for bulk, directly defines a port’s competitiveness. Simultaneously, intermodal logistics ensures the smooth handoff of cargo to trucks or trains, requiring precise scheduling and yard management to avoid bottlenecks.

Navigational Services and Ship Support ensure vessels can safely access and depart the port. This includes maintaining dredged channels to sufficient depth, providing pilotage (where expert local pilots board to guide the ship in), towage (using tugboats to maneuver large vessels), and berthing assistance. The port authority’s Vessel Traffic Service (VTS) acts like an air traffic control for shipping lanes, monitoring movements and preventing collisions in congested waters.

The implementation of Safety, Security, and Regulatory Compliance is a non-negotiable function. Ports are high-risk environments. Safety protocols protect workers from accidents involving heavy machinery and hazardous cargo. Security, mandated by the ISPS Code, involves access control, perimeter monitoring, surveillance, and coordination with national agencies to counter threats. As noted in industry analyses, threats are evolving; for instance, 2025 saw a marked increase in armed robbery incidents in the Singapore Strait, with criminals transitioning from petty theft to more daring, armed boardings. Ports must have plans for different MARSEC (Maritime Security) Levels, escalating measures from routine (Level 1) to exceptional (Level 3) in response to specific threats. Furthermore, ports facilitate customs inspection, immigration control, and agricultural quarantine, acting as the state’s border control checkpoint for maritime arrivals.

Finally, ports provide Commercial and Value-Added Services. These turn a port from a transit point into a logistics and industrial hub. Services include cargo consolidation and deconsolidation, warehousing, labeling, light assembly (postponement), and logistics management. Many ports host related industries like refineries, chemical plants, or manufacturing, creating port-centric clusters that benefit from direct access to sea transport.

–

Challenges and Practical Solutions in Modern Port Operations

Operating a 21st-century seaport involves navigating a complex array of persistent and emerging challenges. One of the most pressing is congestion and capacity constraints. As container ships grow ever larger (now exceeding 24,000 TEU capacity), ports face immense pressure to handle peak volumes without delays. Congestion at a single major port can cascade into global supply chain disruption. The solution is a multi-pronged approach focusing on physical expansion (deepening channels, building new terminals), operational digitalization, and improving hinterland connections. Implementing port community systems that digitally connect all stakeholders—shipping lines, terminals, truckers, customs, and railways—can dramatically improve planning and fluidity.

Security threats remain a dynamic and severe challenge. While large-scale piracy has declined in some regions due to coordinated naval patrols, it persists in others. The Gulf of Guinea, for example, remains a high-risk area where the underlying drivers—such as poverty, weak governance, and oil-related crime—persist despite a decline in incident numbers. Meanwhile, the crowded Singapore Strait has seen a surge in armed robbery against ships, requiring heightened vigilance and regional patrols. The practical solution extends beyond onboard security to robust port and coastal surveillance. Ports must rigorously implement the ISPS Code, which includes conducting regular security assessments, maintaining detailed Port Facility Security Plans (PFSPs), and ensuring close cooperation with coastal states and reporting centers like the IMB Piracy Reporting Centre.

The technological and cybersecurity challenge is twofold. Ports must invest in automation (automated guided vehicles, robotic cranes) and data analytics to stay efficient. However, this increased connectivity makes them prime targets for cyber-attacks that could cripple operations. The industry response involves developing new cybersecurity guidelines that complement the ISPS framework, investing in secure IT infrastructure, and training personnel to recognize digital threats.

Finally, environmental regulations and the push for decarbonization present a major strategic challenge. Ports are significant sources of local air pollution (from ships, trucks, and equipment) and must comply with stricter emission control areas. The global push for net-zero shipping forces ports to adapt. Solutions include providing shore power (cold ironing) so docked ships can turn off their engines, incentivizing the use of low-sulfur fuels, developing infrastructure for alternative fuels like green hydrogen and ammonia, and optimizing port calls to reduce ship waiting times and associated emissions.

–

Case Studies: Real-World Applications of Port Specialization and Adaptation

The Port of Singapore: A Transshipment Titan Embracing Technology and Security

The Port of Singapore exemplifies the evolution into a hyper-efficient, technology-driven global hub. Its primary function is transshipment, strategically leveraging its location on the Strait of Malacca, the world’s busiest shipping lane. To maintain its edge, Singapore has heavily invested in automation, with terminals like Pasir Panjang utilizing automated quay cranes and driverless vehicles. It also serves as a pivotal maritime services center, hosting a vast ecosystem of shipbrokers, financiers, insurers, and classification societies like DNV and ClassNK.

Facing the very real security challenges of its surrounding waters, the Port of Singapore Authority works closely with regional partners through frameworks like ReCAAP (Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia). This cooperation was evident in 2025 when a coordinated response with Indonesian authorities led to arrests that curbed a spike in incidents. Furthermore, Singapore proactively manages operational risks, as seen in its public advisories for monsoon season safety, detailing procedures for vessel securing, crew safety, and increased port state inspections to prevent accidents. This blend of global connectivity, technological leadership, and proactive safety and security management solidifies Singapore’s status as a benchmark port.

The Ports of the Gulf of Guinea: Gateways Navigating Complex Security Challenges

The ports along the Gulf of Guinea, such as Lagos (Nigeria) and Tema (Ghana), serve as crucial gateway ports for West African economies, exporting raw materials and importing essential goods. Their operational reality is shaped by the significant maritime security challenges in their adjacent waters. Unlike the transshipment model, these ports are endpoints, and the threat of piracy and kidnap-for-ransom directly impacts shipping costs, insurance premiums, and crew welfare for vessels calling there.

The response has involved a multi-layered regional approach. The Yaoundé Architecture facilitates information sharing and coordination between West African navies. Nigeria has invested in its “Deep Blue” project, a integrated maritime security system. Ports themselves enforce strict ISPS Code measures, and international navies provide support, albeit with complex legal and sovereignty considerations. This case highlights how a port’s function and success are inextricably linked to the security of its wider maritime domain, requiring solutions that address not just port security but also the onshore socio-economic root causes of maritime crime.

–

Future Outlook and Maritime Trends for Seaports

The seaport of the future will be smarter, greener, and more integrated. Digitalization and the Internet of Things (IoT) will advance beyond current systems, with digital twins (virtual replicas of the entire port) used for simulation, optimization, and predictive maintenance. Artificial Intelligence (AI) will optimize every process, from ship scheduling and yard planning to predictive equipment repair, drawing on massive datasets to make decisions in real-time. As seen in defense sectors, AI-powered automatic recognition and tracking systems, currently explored for threat detection, will likely filter into commercial port security for monitoring vessel traffic and perimeter intrusion.

Automation will expand from terminals to the entire port ecosystem, encompassing automated mooring systems, drone-based deliveries of ship spares, and autonomous trucks for hinterland transport. This shift will change the nature of port employment, requiring more highly skilled technicians and data analysts.

The imperative for decarbonization and green ports will accelerate. Ports will transform from energy consumers to clean energy hubs. This involves full electrification of equipment, large-scale generation of renewable energy (solar, wind) within port areas, and crucially, becoming the infrastructure providers for the future fuel supply chain, whether for LNG, methanol, hydrogen, or ammonia. The green port will also focus on circular economy principles, managing waste and promoting sustainable dredging.

Finally, resilience and adaptability will be paramount. Ports will need to physically adapt to climate change impacts like sea-level rise and stronger storms. Supply chain resilience will be built through data-sharing platforms that provide end-to-end visibility and through strategic diversification to avoid over-reliance on single trade routes or chokepoints, lessons underscored by recent global disruptions.

FAQ Section

1. What is the difference between a port and a terminal?

A port is the entire, overarching administrative and geographic area that includes all the facilities, waterways, and land. A terminal is a specific, specialized facility within a port dedicated to handling a particular type of cargo. For example, the Port of Rotterdam contains the Maasvlakte 2 container terminal, the Botlek liquid bulk terminal, and the Vlaardingen fruit terminal, among many others.

2. What does “port of call” mean?

A port of call is simply any port where a ship stops during its voyage to load or unload cargo, embark or disembark passengers, or take on supplies and fuel. A ship’s itinerary is a list of its scheduled ports of call.

3. Who is responsible for security in a port?

Security is a shared responsibility under the ISPS Code. The Port Facility Security Officer (PFSO) is responsible for implementing the Port Facility Security Plan. The Ship Security Officer (SSO) is responsible for security on board a vessel. The Company Security Officer (CSO) oversees security for the shipping company. They all must coordinate with each other and with the Designated Authority (usually a national coast guard or maritime agency) of the port state.

4. What is the largest type of seaport in the world?

By volume of cargo handled and economic impact, container ports are the largest and most dominant type. The world’s biggest ports, like Shanghai, Singapore, and Ningbo-Zhoushan, primarily handle containerized cargo. However, in terms of physical cargo tonnage, some major bulk ports (like Port Hedland in Australia, which exports iron ore) can rival them.

5. How do seaports impact the local economy?

Seaports are powerful economic engines. They create direct employment in cargo handling, transportation, and logistics. Indirectly, they support jobs in industries that use the port for trade. Ports also generate significant tax revenue, attract port-related industries (e.g., distribution centers, refineries), and enhance the region’s connectivity to global markets, which is a key factor for business investment.

6. What are “hinterland” and “foreland” connections?

A port’s hinterland is the inland region from which it draws exports and to which it distributes imports—its economic catchment area by land. Its foreland is the distant regions overseas with which it trades by sea. A port’s success depends on efficient transport links to both.

7. What is a “free port” or “free trade zone”?

A free trade zone (FTZ) within a port is a designated area where goods can be landed, stored, processed, or re-exported with reduced customs duties, taxes, or streamlined regulations. It is designed to encourage trade and investment by reducing bureaucratic barriers within the zone.

Conclusion

From ancient harbors to today’s automated, sprawling logistics complexes, seaports have always been civilization’s gateways to the world. As we have explored, a modern seaport is a multifaceted entity: a specialized industrial hub, a critical security checkpoint, and a vital link in the global supply chain. Its functions extend far beyond the simple transfer of goods, encompassing navigation services, regulatory compliance, and value-added logistics that drive regional and national economies. The challenges ports face—from congestion and cyber-threats to piracy and the urgent need for decarbonization—are microcosms of the broader issues confronting global trade. By embracing trends in digitalization, automation, and green technology, ports are actively shaping a more efficient, resilient, and sustainable future for maritime commerce. Understanding these dynamic nodes is fundamental to understanding the flow of goods, energy, and prosperity that connects our world. To continue learning about the specific technologies and security frameworks that keep these complex systems running, we encourage you to explore our platform’s further resources on port terminal automation, the ISPS Code in depth, and maritime decarbonization strategies.

References

-

International Chamber of Commerce (ICC). International Maritime Bureau (IMB). (2025). Cautious optimism prevails despite uptick in reported maritime piracy attacks .

-

Thompson, B. (2025, August 15). International Ship and Port Facility Security (ISPS) Code – Complete Guide for Ships and Ports. InCode Docs .

-

Atlantic Council. (2025). Atlantic piracy, current threats, and maritime governance in the Gulf of Guinea .

-

Maritime Fairtrade. (2025). Surge in Maritime Crime Threatens Singapore Strait in 2025 .

-

ICC International Maritime Bureau (IMB). (2025). IMB Piracy & Armed Robbery Map 2025 .

-

London Maritime Academy. (2024, May 25). Implementing the ISPS Code: Challenges and Best Practices .

-

Williams, M. (2024, May 15). Gulf of Guinea Maritime Security: Lessons, Latency, and Law Enforcement. War on the Rocks .

-

Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore (MPA). (2025, December 4). Staying Safe at Sea during the Monsoon Season 2025 .

-

DefenseScoop. (2025, October 6). Navy eyes AI to track adversarial drone swarms, vessels from maritime helicopters .

-

Wikipedia. (2025). 2025 in piracy .

-

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (2024). Review of Maritime Transport.

-

International Maritime Organization (IMO). International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), Chapter XI-2 and the ISPS Code.