As Arctic shipping expands due to melting sea ice and new trade corridors, fragile ecosystems face severe threats—from pollution and soot to underwater noise and invasive species.

For most of history, the Arctic Ocean was a fortress—ice-locked, inhospitable, and commercially irrelevant. Today, due to accelerated warming and the retreat of multi-year sea ice, the region is opening to maritime traffic at a speed unmatched by any other ocean basin. Cargo vessels, LNG carriers, tankers, ice-class container ships, and cruise ships now enter waters that only a decade ago were unnavigable for nine months of the year.

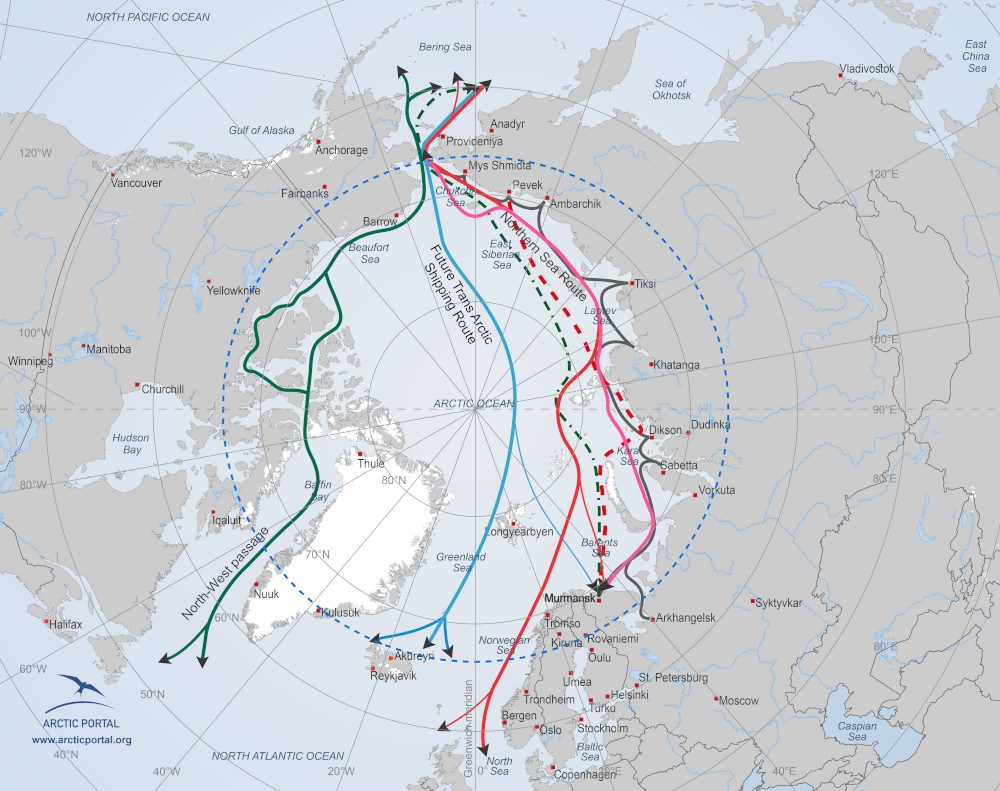

The North Sea Route along Russia’s Siberian coastline and the Northwest Passage connecting the Atlantic and Pacific are no longer hypothetical transit fantasies. They are emerging corridors of global commerce. What this means for shipping is historic efficiency: shorter distances, lower fuel costs, reduced transit times between Asia and Europe, and entirely new logistics and port economies.

But what this means for the Arctic ecosystem is something else entirely. More ships in previously untouched waters mean more black carbon, more underwater noise, more invasive species, more spill risk—and far more stress on marine mammals that have never evolved to endure industrial maritime presence.

Why Arctic Routes Are Expanding

Climate Change as the Enabler

Sea ice is thinning earlier and reforming later each year. Transit windows that once lasted two weeks now last months. Some projections indicate ice-free summers by mid-century. Every degree of warming enlarges navigable corridors and reduces icebreaker dependency.

Geopolitical and Economic Drivers

Global trade realignment following the Russia–Ukraine conflict, the rise of Asia-centered supply chains, and the search for non-Suez, non-Hormuz alternatives push governments and shipping lines toward Arctic diversification. Russia, China, the U.S., Canada, Norway, and Iceland see both economic advantage and strategic leverage in ice-free passageways.

–

The Ecological Cost of Newly Open Waters

Ports and Ice-Class Construction

New Arctic terminals and shipyards promise jobs and strategic power, but bring dredging, blasting, underwater construction, and seabed disturbance to pristine benthic habitats.

Icebreakers and Channel Making

Icebreaking does not simply “clear paths.” It changes coastal drift, breaks multi-year structures vital to seal hunting and polar bear denning, and accelerates ice-edge retreat.

Shadow Commerce

As global sanctions push Russian hydrocarbon flows eastward through the Arctic, monitoring gaps widen:

- AIS signal masking

- older vessels

- reduced Western insurance oversight

The ecological risk multiplies when commercial volume grows faster than safety governance.

Arctic Whales Impacted by Continued Increase in Maritime Traffic. The narwhal is an important resource in Inuit culture. (Photo: Wikipedia)

Arctic Species Most at Risk

-

Bowhead and Narwhal Whales: hyper-acoustic species sensitive to ship noise.

-

Polar Bears: dependent on sea ice for hunting, reproduction, and movement.

-

Walruses: stampede mortality increases when startled by ship engines.

-

Arctic Cod: keystone fish species threatened by noise and invasive predators.

-

Krill and Plankton: foundation of the Arctic food web, vulnerable to temperature and chemical disruption.

Arctic megafauna are slow-breeding; population recovery is measured not in years but in generations.

–

Climate Feedback: Global Consequences Beyond the Region

The melting of Arctic sea ice is not a remote, isolated phenomenon; it serves as a powerful destabilizing force for the entire planetary climate system. As the reflective white ice—which functions as Earth’s natural mirror—retreats, it is replaced by darker ocean waters that absorb significantly more solar heat, a process known as albedo loss that directly accelerates the pace of global warming. This fundamental shift in the polar energy balance radiates outward, weakening the established patterns of the jet stream. This atmospheric disturbance manifests globally as an increase in persistent and extreme weather events, from devastating heatwaves to paralyzing winter storms. Furthermore, the influx of cold, fresh meltwater into the North Atlantic threatens to disrupt the great ocean conveyor belt, the system of currents that regulates climate and nourishes fisheries from northern Europe to the tropics. In this light, the Arctic is more accurately understood not as a distant region, but as the planet’s vital cooling system. The expansion of industrial shipping directly compromises this critical thermostat function, with consequences that reverberate far beyond the polar circle.

Melting sea ice does not just threaten Arctic life. It destabilizes Earth’s entire climate system:

-

Loss of albedo accelerates global warming.

-

Jet stream patterns weaken, increasing extreme heatwaves and winter storms.

-

Ocean currents shift, affecting fisheries from the North Atlantic to the tropics.

The Arctic is often described not as a region but as Earth’s cooling system—and shipping expansion weakens its thermostat function.

–

Future Outlook: Development vs. Fragility

The trajectory of the coming decade will determine the ultimate fate of the Arctic, defining whether it becomes a new, bustling Silk Road of polar commerce or a profound cautionary tale of ecological overshoot and irreversible loss. The central tension lies between the rapid pace of economic ambition and the slower implementation of protective governance. While a suite of sustainability mechanisms exists in theory—including mandatory zero-soot fuel standards, slow-steaming regimes to reduce noise and emissions, seasonal exclusion zones to protect marine mammals, advanced ballast water biocontrol, strict limits on cruise tourism capacity, and taxation on black carbon emissions—their adoption and enforcement consistently lag behind the speed of commercial opportunity. The fundamental challenge is one of velocity: unless regulatory frameworks are established and empowered to move faster than industrial exploration and infrastructure development, the irreversible momentum of commercial access will permanently outpace our capacity for meaningful ecological protection, locking in a future defined by fragility rather than resilience.

–

Conclusion

The Arctic may represent the final major frontier of global shipping expansion. It is also the last ecosystem least capable of absorbing disruption. As sea lanes widen, emissions rise, sonar deepens, ports expand, and trade intensifies, the region faces stressors beyond any natural adaptation capacity.

The Arctic cannot negotiate with diesel exhaust.

It cannot accelerate its reproductive cycles.

It cannot outrun ballast water.

The maritime sector stands at an inflection point: to treat the Arctic as a corridor of convenience, or as a living climate regulator whose protection is inseparable from the stability of Earth’s oceans, coasts, and trade.

Global commerce may benefit from an ice-free route, but the planet will not easily mourn what is lost beneath the hulls that travel it.

–

References

-

International Maritime Organization (IMO), Polar Code Guidance

-

Arctic Council, Protection of Arctic Marine Ecosystems Report 2024

-

WWF Arctic Programme, Black Carbon and Sea Ice

-

UNEP, Polar Biodiversity and Climate Vulnerability

-

Lloyd’s Register, Arctic Shipping Risks and Ice-Class Trends

-

Marine Mammal Commission, Noise Disturbance and Cetacean Behavior

-

NOAA, Arctic Sea Ice Decline and Ocean Systems

-

DNV Maritime, Northern Sea Route Safety Framework

-

European Space Agency, Cryosphere and Albedo Decline Analysis

-

IUCN, Arctic Species Red List Vulnerability