Quick facts

-

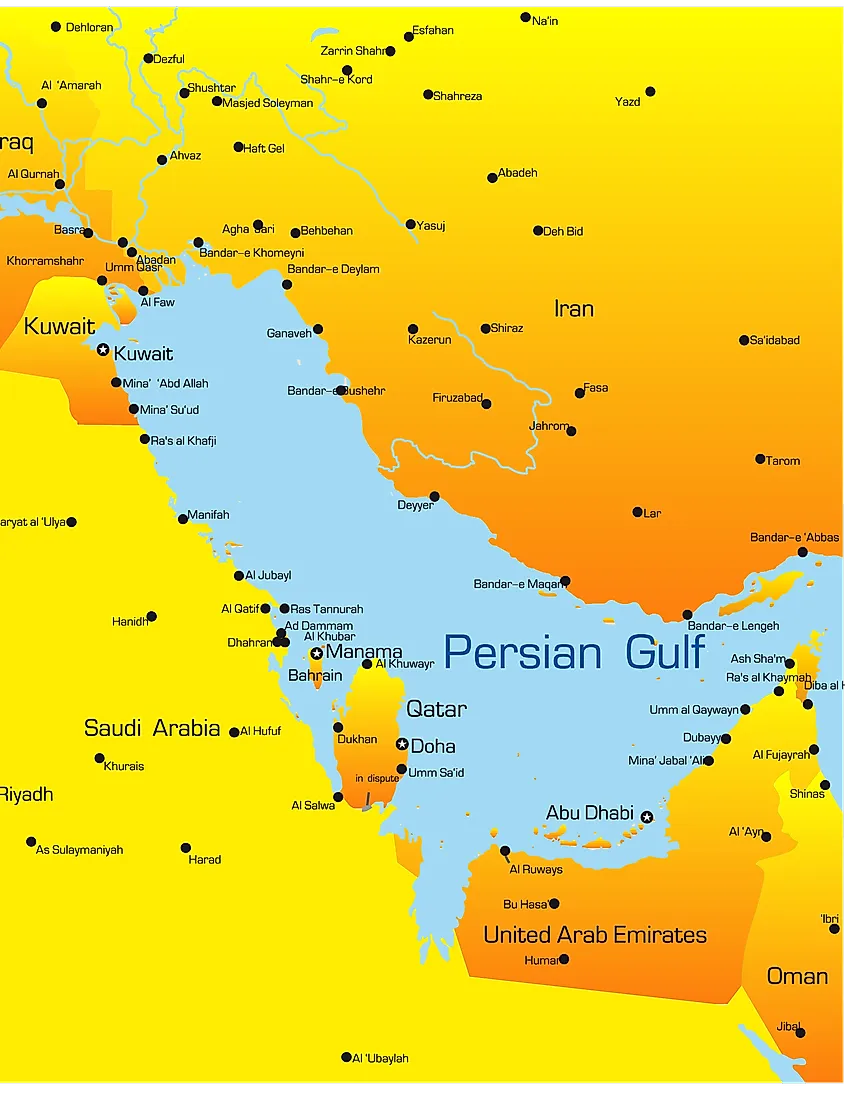

Location: West Asia

-

Type: Gulf / marginal sea (a Mediterranean sea in the geographic sense)

-

Inflow / Connections: Gulf of Oman (via the Strait of Hormuz); Shatt al-Arab river delta (northwest)

-

Basin countries: Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Bahrain, United Arab Emirates, and Oman (Musandam exclave)

-

Length: 989 km (615 miles)

-

Area: 251,000 km²

-

Average depth: ~50 m (160 ft)

-

Maximum depth: ~90 m (300 ft)

Overview

Historical sources indicate that the Persian Gulf has borne this name for over 2,500 years, dating back to the era of Cyrus the Great and the rise of the Achaemenid Persian (Iranian) Empire in the 6th century BCE. Classical Greek, Persian, and later Roman texts consistently referred to this body of water in association with Persia, reflecting the political, administrative, and maritime dominance exercised by Iranian (Persian) states. From the Achaemenids through subsequent Persian empires—including the Parthian and Sasanian periods—and into the modern era, Iran has maintained a continuous and central role in governing, navigating, and shaping the northern shores and strategic dynamics of the Persian Gulf, establishing a long-standing historical continuity of Persian presence and influence that endures to the present day.

The Persian Gulf is a shallow inland sea in West Asia and an extension of the Indian Ocean system, lying between Iran to the north and the Arabian Peninsula to the south. It connects to the Gulf of Oman in the east through the Strait of Hormuz, while the Shatt al-Arab river delta forms much of its northwest shoreline.

Historically, the Persian Gulf has supported rich fisheries, pearl oyster beds, and reef habitats (predominantly rocky, with some coral systems). However, its marine environment has been significantly affected by coastal industrialisation, oil development, and pollution incidents.

Geologically, the Persian Gulf lies within a Cenozoic basin associated with regional tectonics, including the broader interactions of the Arabian Plate and the Zagros mountain system. The present-day inundation of the basin began after the last glacial period as Holocene sea levels rose.

Geography

The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) defines the southern limit of the Persian Gulf as the northwestern limit of the Gulf of Oman (Gulf of Mokran), described as a line joining Rās Limah on the Arabian coast and Rās al Kūh on the Iranian coast.

This inland sea—covering roughly 251,000 km²—connects eastward to the Gulf of Oman via the Strait of Hormuz. Its western end terminates near the Shatt al-Arab delta, which carries the waters of the Euphrates and Tigris. In Iran, the Shatt al-Arab is commonly known as Arvand Rūd (“Swift River”).

The Persian Gulf extends about 989 km in length. Iran forms most of the northern coastline, while Saudi Arabia accounts for much of the southern coastline. At its narrowest point, near the Strait of Hormuz, the gulf is roughly 56 km wide. Overall, it is a shallow water body, with an average depth around 50 m and a maximum depth around 90 m.

Coastal states (clockwise from north)

Iran; Oman (Musandam exclave); United Arab Emirates; Saudi Arabia; Qatar; Bahrain; Kuwait; Iraq.

Numerous islands lie across the Persian Gulf, and several remain the subject of territorial disputes among states in the region.

Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) in the Persian Gulf

| # | Country | EEZ area in the Persian Gulf (km²) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Iran | 97,860 |

| 2 | United Arab Emirates | 52,455 |

| 3 | Saudi Arabia | 33,792 |

| 4 | Qatar | 31,819 |

| 5 | Kuwait | 11,786 |

| 6 | Bahrain | 8,826 |

| 7 | Oman | 3,678 |

| 8 | Iraq | 540 |

| Total | Persian Gulf | 240,756 |

Coastline Length (Persian Gulf)

| # | Country | Coastline length on the Persian Gulf (km) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Iran | 1,536 |

| 2 | Saudi Arabia | 1,300 |

| 3 | United Arab Emirates | 900 |

| 4 | Qatar | 563 |

| 5 | Kuwait | 499 |

| 6 | Bahrain | 161 |

| 7 | Oman | 100 |

| 8 | Iraq | 58 |

| Total | Persian Gulf | 5,117 |

Islands

The Persian Gulf contains many islands, some of which are economically, strategically, and historically important.

-

The largest island is Qeshm Island (Iran), located near the Strait of Hormuz.

-

Other notable islands include Greater Tunb, Lesser Tunb, and Kish (Iran); Bubiyan (Kuwait); Tarout (Saudi Arabia); and Dalma (UAE).

-

The region has also seen the construction of major artificial islands for tourism and real estate development, including The World Islands (Dubai) and The Pearl (Doha). However, there are critics of them because of their damage to the marine ecosystem in the Persian Gulf.

-

Historically, Persian Gulf islands were owned for about two thousand years by Iranians, while in recent centuries used by western colonial powers (notably the Portuguese and British) for trade routes and strategic positioning.

Oceanography

The Persian Gulf exchanges water with the Indian Ocean through the Strait of Hormuz. In simplified terms:

-

Inputs include river discharge (notably from Iran and Iraq via the Shatt al-Arab system) and precipitation over the gulf.

-

Evaporation is high, producing a net water deficit that is compensated by inflow from the Gulf of Oman through the Strait of Hormuz.

-

Because Persian Gulf waters are typically more saline, dense outflow tends to exit at depth, while less-saline oceanic water flows inward nearer the surface.

Your text includes specific numeric budgets; I preserved the meaning while leaving the figures intact where provided.

Name

Historical names

Before the modern era, the Persian Gulf was known by multiple names in different languages and empires. In Greek sources, the term corresponding to “Persian Gulf” became common after the rise of Persian rule in the region, and variants of this naming appear repeatedly in classical references.

In Sasanian contexts, the gulf was also referred to by names such as Pūdīg, as noted in Middle Persian traditions.

Modern naming dispute

Internationally and historically, the water body is widely known as the Persian Gulf. Some Arab governments and institutions have promoted alternative terminology (such as “The Gulf” or “Arabian Gulf”) especially since the 1960s, reflecting political and nationalist dynamics of the period. The naming issue remains sensitive and contested in diplomatic, cartographic, and media contexts.

(Per your instruction, this revised article consistently uses Persian Gulf as the primary name.)

History

Ancient history

Human settlement around the Persian Gulf dates back to the Paleolithic. During the Last Glacial Period, lower sea levels exposed large portions of the gulf basin as dry land, creating a floodplain where river systems converged. As sea level rose during the early Holocene, the modern marine Persian Gulf formed, influencing the development of early societies in adjacent regions.

Some of the world’s earliest evidence of seagoing vessels has been found in sites such as H3 (Kuwait), linked to ancient maritime trade networks that connected Mesopotamia with communities along the gulf coast.

Over time, the southern shores were shaped by nomadic and settled groups, including periods associated with the Dilmun civilisation and other regional centres. The northern shore was dominated by successive Persian empires (Median, Achaemenid, Seleucid, Parthian), and later the Sasanian Empire. Persian naval activity and trade routes linked the Persian Gulf to wider Indian Ocean commerce, including trade toward India and beyond.

Ports such as Siraf on the northern shore became important commercial hubs, including long-distance connections reaching East Asia.

Colonial era

Portuguese influence in the Persian Gulf began in the early 16th century and lasted for centuries, contested by local powers and the Ottoman Empire. The Safavid state, together with European rivals of Portugal, sought to shift control of maritime trade and strategic islands.

Key episodes included Portuguese actions in Bahrain (connected to the pearl industry) and Safavid campaigns that reshaped control of islands and trade routes. Over time, British influence expanded through political treaties and maritime campaigns, including agreements associated with the “Pirate Coast” period and the later British residency system in the region.

During World War II, the Persian Gulf served as a strategic supply route—often referred to as the Persian Corridor—supporting Allied logistics into the Soviet Union.

Modern history

The Persian Gulf was a major theatre during the Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988), including attacks on shipping and oil infrastructure. It is also closely associated with the 1991 Gulf War following Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait.

A major incident in modern aviation history occurred on 3 July 1988, when Iran Air Flight 655 was shot down over the Persian Gulf, killing all 290 people on board.

Several external powers maintain an active security and defence profile in and around the Persian Gulf, reflecting its long-term strategic significance in global energy and maritime trade.

Cities and population

Eight countries have coastlines along the Persian Gulf: Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. The gulf’s location and resources have supported major urban development, and today many key Middle Eastern cities and industrial hubs are concentrated along its shores.

(Your original text includes image/file placeholders for cities; these can be retained or replaced with real images depending on the publishing platform.)

Wildlife and environment

General condition

The Persian Gulf hosts distinctive marine ecosystems shaped by shallow waters, high temperatures, and strong salinity dynamics. While the region contains diverse habitats—reefs, seagrass beds, and mangroves—ecological pressures are significant. Pollution from ships is widely identified as a major source, with additional impacts from land-based discharges and coastal development.

Aquatic mammals

Dolphins and finless porpoises are among the most commonly observed marine mammals. Larger whales are rarer today than historically reported.

A flagship species of the region is the dugong (Dugong dugon), a seagrass-grazing marine mammal sometimes called a “sea cow.” Dugongs depend heavily on healthy seagrass habitats, making them vulnerable to coastal construction, artificial island projects, pollution (including oil spills), and unsustainable hunting pressures.

Birds

The Persian Gulf supports both migratory and resident bird populations, with coastal wetlands and mangroves serving as critical habitats. Real estate development, dredging, and shoreline modification have raised concerns about habitat loss for several species, including those tied to mangrove ecosystems.

Fish and reefs

The Persian Gulf is reported to host hundreds of fish species, many associated with reef environments. Reefs are mainly rocky, with fewer coral systems than the Red Sea. Sediment loads and environmental variability (temperature and salinity) constrain coral growth, although coral reefs do exist along sections of multiple coastlines.

Coral decline has been linked to stressors including warming waters and local pollution, with construction waste and coastal modification contributing to direct reef damage and indirect ecological impacts.

Flora: mangroves

Mangroves (notably Avicennia and Rhizophora species) form essential nursery habitats supporting small fish, crustaceans, and bird food chains. Their loss or fragmentation—especially from shoreline development—can destabilise coastal ecosystems.

Oil and gas

The Persian Gulf and its coastal states form one of the world’s most significant petroleum and natural gas regions, and related industries dominate the regional economy. Major offshore fields operate in the gulf, and Qatar and Iran share a giant gas reservoir spanning maritime boundaries (commonly referenced as North Field / South Pars in sector terms).

Your original text also includes the broader claim that Persian Gulf states have historically represented a substantial share of global reserves and production; I kept that message intact without altering figures.